Reviewing the last U.S. Supreme Court 2022 term, the highest court decided several high-profile cases involving intellectual property rights. The keyword among these cases is “limitation.” There are limitations on the breadth of particular areas of IP law. These limitations will affect the IP holder’s rights, as well as those who are infringing those rights. The major copyright case before the Court was decided in May, and this posting will quickly review the implications of that ruling.

Before going into the merits of the case, there are a few introductory questions to ask.

What is copyright fair use?

The U.S. Copyright Act is the federal law that protects creative works fixed in a tangible medium of expression (17 U.S.C. §101). There are several enumerated exceptions to copyright protection, which includes the fair use exception (17 U.S.C. §107).[1] The Copyright Act enumerates several other exceptions, but only fair use is relevant to the recent U.S. Supreme Court case.

What is transformative use?

Transformative use is the way a work uses a previously created work as inspiration or a model for that new work. It is technically a derivative work off of the previous work.

Transformative use is analyzed under the first prong – purpose and character of the use – of the fair use exception to copyright protection. Transformation is important because although it is a derivatively created work, it could be so transformed completely with its own originality to be deemed a new work.

What did the U.S. Supreme Court hold in the Warhol case?

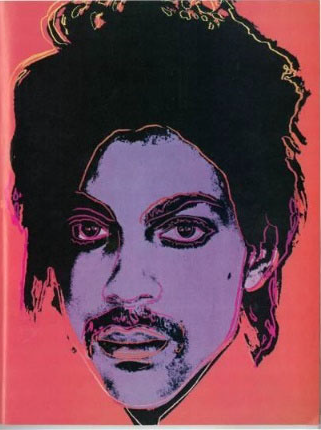

In Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith,[2] the Supreme Court recently held that the Andy Warhol Foundation’s use of Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince in the early days of his career was not fair use because the AWF’s use was not transformative.

The Court focused on AWF’s commerciality of the purpose and nature of its use of Goldsmith’s work.

Specifically, AWF obtained a proper license to Goldsmith through Vanity Fair for the Prince photograph to be used as a reference for Andy Warhol to create his so-called Orange Prince collection.

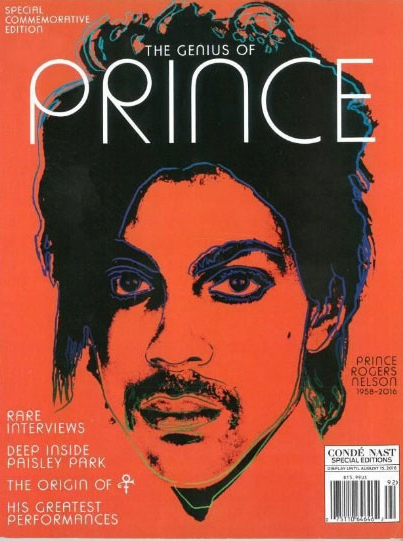

However, AWF then licensed the Orange Prince collection to Condé Nast. This second licensing by AWF was at-issue in the case before the Court.

The Court noted that the right of derivation rests with the original work’s owner. Yet, the Court also noted that remaking of the original work for purposes of criticism, commentary or parody could transform what would be an infringing use into a wholly new creative work independent of the original work.

The Court reasoned that a justification to take away the original owner’s right to adapt must be one that has a distinct purpose in furthering the goals of copyright law, which is to promote the arts and sciences without affecting the incentives to create. So, the Court looked at how AWF’s nature of its infringing use, and focused particularly on the commercial nature of how AWF took a properly licensed use (i.e., Warhol’s license of Goldsmith’s original photograph), and turned it into further, technically infringing use for commercial profit. This purpose made AWF’s use, then, not transformative, and therefore, not fair use.

Takeaways

- Photographers and other digital arts creators have stronger copyright protections of their works in a post-Warhol world. Before Warhol was decided, would-be infringers could simply claim “transformative use,” and many times a federal court will hold that the use was not infringing. Also, there was an uneven patchwork of different rulings from different federal courts. The rule set by Warhol Court is not perfect but it does create some bright lines in which lower courts will now need to follow.

- Although the nature of an infringer’s commercial purpose of the use tends to not be a finding of fair use, and inversely a noncommercial purpose would tend toward a finding of fair use), this is not a hard-and-fast rule. The other aspects of the first prong must be analyzed with the other three factors of the fair use test.

- Keep in mind that fair use is an affirmative defense to copyright infringement. In other words, you know you are using another’s work in creating your own work. Defending a federal case is expensive – it’s just better to use your own imagination to create your own original work. Or…

- … If you must use another’s work as the template to build your own work, you will need to obtain permission from the actual owner or negotiate a license. Relying on transformative use defense as a basis is risky and could cost more rather than getting the actual owner’s consent.

- Licensing and permissions is a subset of the copyright practice. What licensees should takeaway is that one license for using one of another’s work is not license for further uses to create new works. Each permission to use should be properly negotiated and license fee paid, if any, for that use.

- There are added complications when creating a work based off another’s work using an AI interface like ChatGPT, Bard AI, Bing AI, or YouChat. AI is the next frontier for intellectual property law, and many areas have yet been tested in the courts. Artists should create with caution.

For more information the Warhol case, copyright law, fair use, or intellectual property, please contact Yonaxis I.P. Law Group.

[1] Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

[2] 598 U.S.___ (2023) (Case No. 21-869 [U.S. May 18, 2023]), aff’g 11 F.4th 26 (2d Cir. 2021), rev’g 382 F. Supp. 3d 312, 316 (S.D.N.Y. 2019).