Fed Circuit Watch: Pre-Critical Date Surgeries Not Invalidating Public Uses

In the first split precedential decision of 2019 by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, the Fed Circuit assessed the issues of invalidating public disclosure versus an inventor’s exception to experimentally perfect an invention for its intended purpose. That case, Barry v. Medtronic, Inc.,1 decided on January 24, 2019, split heavily because of the fact-specific nature of evidence, with the majority finding experimental use, and a vocal dissent finding invalidating public use.

Dr. Mark Barry invented a method and a system for scoliosis-induced spinal anomaly correction, performed through a surgical procedure. Dr. Barry worked in 2002-2003 on the various technical aspects of the apparatus and surgical process. The resulting tool was used in three surgeries – August 4, August 5, and October 14, 2003. Dr. Barry assessed the success of the invention through follow-up appointments to determine success of the surgeries on correction of spinal anomalies. Satisfied with the results, he proceeded to write an article summarizing his findings for a professional conference in April 2004, and then filed a patent application on December 30, 2004, which resulted in U.S. Patent No. 7,670,358 (‘358). Thus, the critical date for the ‘358 patent is December 30, 2003 for purposes of the public use doctrine under 35 U.S.C. §102(b) (MPEP 2133).

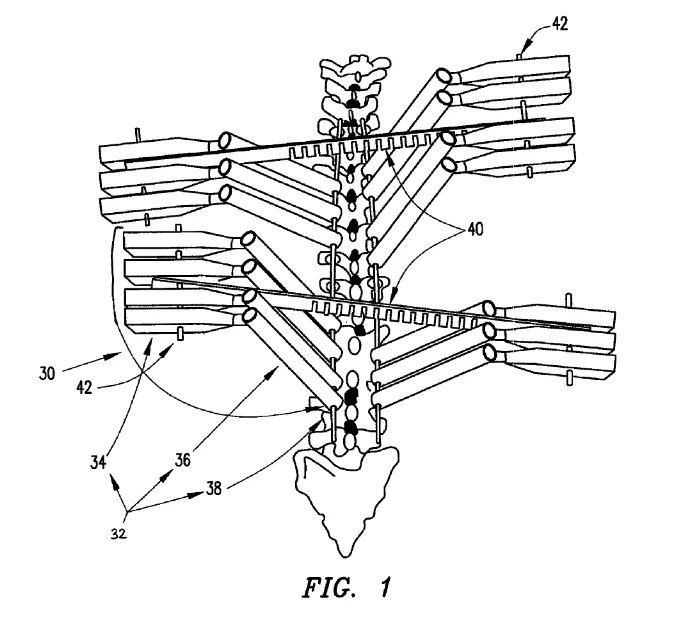

Figure 1 illustrates the invention.

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,670,358 B2, Mar. 2, 2010, to Mark A. Barry (inventor)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,670,358 B2, Mar. 2, 2010, to Mark A. Barry (inventor)

Medtronic also had work in spinal derotation correction, with one of its inventors starting work in 2002. In 2006, Medtronic introduced its own spinal correction surgical kit. Dr. Barry sued Medtronic for a number of causes of action, including patent infringement and induced infringement of the ‘358 and another patent. Medtronic countered arguing, in part, that the ‘358 patent was already in public use and, therefore, invalid. The district court upheld the jury finding of infringement of claims 4-5 of the ‘358 patent, as well as claims 2, 3, and 4 of the related U.S. Patent No. 8,361,121 (‘121).

If an invention is in public use and ready for patenting before its critical date, that invention is barred from patentability under pre-AIA §102(b) (MPEP 2133.03).2 The experimental use doctrine (MPEP 2133.03(E)) is an exception to the pre-AIA §102(b) patent prohibition, as enunciated by the LaBounty decision:

A use or sale is experimental for purposes of pre-AIA section 102(b) if it represents a bona fide effort to perfect the invention or to ascertain whether it will answer its intended purpose … . If any commercial exploitation does occur, it must be merely incidental to the primary purpose of the experimentation to perfect the invention.3

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Chief Judge Prost, and Judges Moore and Taranto, with Judge Taranto writing for the majority, and Chief Judge Prost in dissent. First, Judge Taranto questioned whether Dr. Barry’s claimed invention in the ‘358 and ‘121 patents was actually “ready for patenting.” He noted:

[Because] the law has long recognized the distinction between inventions put to experimental use and products sold commercially (MPEP 2133.03a) … . Here, Medtronic relied on the August and October 2003 surgeries as reductions to practice that immediately proved the claimed inventions work for its intended purposes (MPEP 2133.03(c)) until January 2004, when he completed the follow-ups on those surgeries, which were on three patients who fairly reflected the real-world range of application of the inventive method.

In other words, from Judge Taranto’s viewpoint, the case against “ready for patenting” fell along very fact-specific evidence.

Second, Judge Taranto concluded Dr. Barry’s invention was used for experimental purposes only, and therefore, was not in “public use.” He did not further question the jury’s finding that Dr. Barry did not know the surgical technique as described in his ‘358 patent would perform for its intended purpose until after, at the least, the last surgery – October 2003. Additionally, he noted that the ‘358 claims do not limit the invention’s intended purpose in any way, and specifically pointed out that the claim 4’s preamble recited an “amelioration of aberrant spinal column deviation conditions,” or a proper wording for what the claimed invention should claim as its “intended purpose.” He outlined the test used to determine experimental use:

(1) the necessity for public testing, (2) the amount of control over the experiment retained by the inventor, (3) the nature of the invention, (4) the length of the test period, (5) whether payment was made, (6) whether there was a secrecy obligation, (7) whether records of the experiment were kept, (8) who conducted the experiment, (9) the degree of commercial exploitation during testing, (10) whether the invention reasonably requires evaluation under actual conditions of use, (11) whether testing was systematically performed, (12) whether the inventor continually monitored the invention during testing, and (13) the nature of contacts made with potential customers.4

Judge Taranto was convinced the trial testimony of Dr. Barry demonstrated that he was not certain that his claimed method would work on different types of scoliosis, and therefore, performed the surgeries in order to test the invention’s claimed purpose. This shows, according to Judge Taranto, experimental use, and specifically, the invention was still under experimentation before the ‘358 patent’s critical date.

Chief Judge Prost, in dissent, believed the ‘358 patent was a prima facie case of “public use” before the critical date in question. Very specifically, while Judge Taranto’s majority opinion determined the surgeries in question were experimental in nature, and not public use, Chief Judge Prost found those surgeries to be, in fact, confirmation that the inventive method performed as to its intended purpose, and therefore, constituted public uses. She cited Dr. Barry’s own testimony:

Q. And there is a term that is used in the patent that is not a term that is familiar to me as a layperson, but it’s amelioration. Does that mean correction?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. So, it happens right there in the operating room, on the spot, true?

A. The surgical correction of the rotated vertebrae back to the midline, yeah, happens with that maneuver. Yes.

Once the surgeries confirmed that amelioration occurred, and the derotated vertebrae was secured by the rods and screws, the inventive method was actually reduced to practice (MPEP 2138.05). Therefore, in her opinion, the surgeries of August and October 2003 were invalidating public uses before the ‘358 patent’s critical date of December 30, 2003.

Further, she noted:

The experimental-use doctrine exists to afford an inventor the ability to experiment with his or her invention via what would otherwise constitute a barring sale or public use. The focus is on the inventor’s intent in making the sale or using the invention publicly; if it is for primarily experimental purposes, we do not consider the sale or use barring. Several factors have emerged to evaluate that intent—e.g., the amount of control the inventor maintained, whether there was a secrecy obligation, the degree of commercial exploitation, and whether customers were aware the inventor was experimenting. Such factors are unrelated to how far along the invention is in terms of reduction to practice. Rather, they bear on the inventor’s intent.

Dr. Barry, however, never informed his patients that the surgeries were experimental in nature, which would militate toward commercialization of his invention, in Chief Judge Prost’s belief. As such, she criticized the majority’s seeming over-analysis of public use doctrine, and the surgeries should be treated very simply as invalidating public uses.

The two opinions were heavily fact-specific. It is a near certainty that because of the ambiguity in two opinions, Medtronic will probably seek petitions for rehearing and/or en banc review. We will continue to update the blog with any further developments in this case.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), aff’g 230 F. Supp. 3d 630 (E.D. Tex. 2017). ↩

-

See Polara Eng’g Inc. v. Campbell Co., 894 F.3d 1339, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2018); see also Pfaff v. Wells Elecs., Inc., 525 U.S. 55, 67 (1998). ↩

-

See LaBounty Mfg. v. United States Int’l Trade Comm’n, 958 F.2d 1066, 1071 (Fed. Cir. 1982). ↩

-

See Allen Eng’g Corp. v. Bartell Indus., Inc., 299 F.3d 1336, 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2002). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent