Fed Circuit Watch: Opioid Addiction Drug Patent Not Obvious

On September 10, 2018, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided Orexo AB v. Actavis Elizabeth LLC,1 in what turns out to be a fairly straightforward analysis of an obviousness case under 35 U.S.C. §103. The facts are as follows.

Orexo owns U.S. Patent No. 8,940,330 (‘330), which describes opioid treatment generally, and is directed to a composition for opioid treatment containing buprenorphine administered in sublingual form. The trade name for the Orexo drug ZUBSOLV®. Actavis filed for an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) under 21 U.S.C. §355(i), which included a Paragraph IV certification, leading to an invalidity litigation in the U.S. District Court, District of Delaware.

Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,940,330, Jan. 27, 2015, to Andreas Fischer (inventor), Orexo AB (applicant/assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,940,330, Jan. 27, 2015, to Andreas Fischer (inventor), Orexo AB (applicant/assignee)

Claims 1 and 6 were deemed representative.

-

A tablet composition suitable for sublingual administration comprising:

microparticles of a pharmacologically-effective amount of buprenorphine, or a pharmaceutically-acceptable salt thereof, presented upon the surface of carrier particles,

wherein microparticles of buprenorphine or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof are in contact with particles comprising citric acid,

wherein the buprenorphine or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof and the citric acid are not in the same particle;

a pharmacologically-effective amount of naloxone, or a pharmaceutically-acceptable salt thereof;

and a disintegrant selected from the group consisting of croscarmellose sodium, sodium starch glycolate, crosslinked polyvinylpyrrolidone and mixtures thereof.

-

The composition as claimed in claim 1, wherein the particles of citric acid are presented and act as carrier particles.

(Emphasis added.)

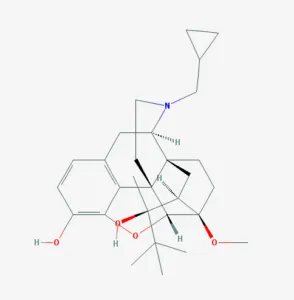

Buprenorphine Chemical Structure, C29H41NO4

Buprenorphine Chemical Structure, C29H41NO4

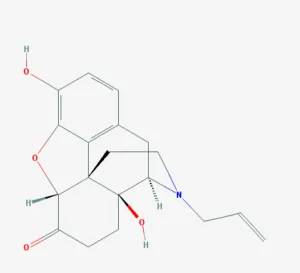

The district court found the ingredients of the ‘330 patent composition – the agonist buprenorphine and the antagonist naloxone – although not shown or suggested in a reference in that specific combination, that combination would have been obvious to a POSITA. For pharmacological purposes, an agonist is a chemical compound which binds to a receptor to activate it to produce a biological response. An antagonist works in the opposite fashion, binding to a receptor to block a biological response. As described in the ‘330 specification, opioid addicts were known to dissolve buprenorphine intravenously to enhance an opioid effect, thereby reducing the efficacy of an opioid treatment drug. The ‘330 patent’s composition included the combination of buprenorphine and naloxone to counteract the abusive aspects of opioid treatment. All parties stipulated that the ‘330 patent was an improvement over the prior art by improving treatment of opioid dependence.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges Newman, Hughes, and Stoll, with Judge Newman writing for a unanimous court. Judge Newman first discussed the prior art for comparative context. SUBOXONE® is a combination of buprenorphine, naloxone, citric acid, and sodium citrate. SUBUTEX® is the same combination without naloxone. Orexo had argued that even during prosecution of the ‘330 patent, the Notice of Allowability stated:

The mere presence of citric acid in the sublingual tablet formulated according to the prior art [SUBUTEX®] is insufficient to achieve the superior pharmacokinetic profile exhibited by the instant invention.2

Naloxone Chemical Structure, C19H21NO4

Naloxone Chemical Structure, C19H21NO4

She also discussed U.S. Patent No. 8,475,832 (‘832), which describes a Suboxone bioequivalent, through a buprenorphine/naloxone combination in a 4:1 ratio. Further, the ‘832 patent teaches an optimum bioavailability of buprenorphine and naloxone at pH 3.0 – 3.5, with citric acid used to lower this pH.

She further discussed another of Orexo’s published patent applications, U.S. Application No. 2010/0129443 (‘443), and issued as U.S. Patent No. 8,470,361, which was cited as prior art against the ‘330 patent during prosecution. The ‘443 application recites a composition where smaller particles of opioid agonists are carried on larger particles that include an opioid antagonist. While the specification describes possible embodiments including agonists, like buprenorphine, and antagonists, like naloxone, it does not describe citric acid nor suggest it as a carrier particle.

The district court held the ‘443 application taught a POSITA would be motivated to combine Suboxone ingredients to improve bioavailability, and the ‘832 patent taught a POSITA to use citric acid to facilitate absorption of buprenorphine. The district court ultimately held that the ‘330 patent claims invalid because it would have been obvious to a POSITA to have combined the elements of the prior art to arrive at the ‘330 patent.

Judge Newman critiqued the district court’s finding of obviousness, noting:

The question is not whether the various references separately taught components of the ‘330 patent formulation, but whether the prior art suggested the selection and combination achieved by the ‘330 inventors.3

Specifically, she critiqued the district court finding:

[T]he district court cited the ‘832 patent to show that “the use of citric acid with an interactive mixture would also improve bioavailability” … . [However, t]here is no suggestion of the different structure of the Zubsolv tablet and its advantage in deterring abuse. [Further, t]he district court cited the Orexo ‘443 Application for its disclosure of particles of buprenorphine adhered to carrier particles. However, the ‘443 application does not mention citric acid in its extensive list of carriers, and does not suggest that citric acid carrier particles may provide benefits compared with the prior art. These benefits were not predicted or suggested in any reference.4

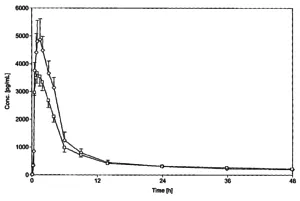

She was further somewhat irritated with the district court’s discounting of the ‘330 patent’s specific 4:1 ratio of buprenorphine-naloxone formulation because no prior art reference or combination of references proposed such a ratio as the ‘330 patent did. The expert testimonies at trial were also discounted, both which showed that the ‘330 patent described a 66% improvement in bioavailability nor the use of citric acid as a carrier particle. Both would support a lack of motivation to combine necessary to conclude a nonobviousness finding (MPEP 2141).

As such, the Fed Circuit reversed the obviousness finding. The case illustrates that while the obviousness inquiry is flexible, the factual findings cannot be discounted if it points to a patent claim being found nonobvious.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), rev’g 217 F. Supp. 3d 756 (D. Del. 2016). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 7). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 15). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 11-12). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent