On March 21, 2018, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled in a split decision in Williams v. Gaye,[1] that the Estate of Marvin Gaye was entitled to broad copyright protection over Gaye’s 1977 hit song “Got to Give it Up,” including its distinctive musical groove, and the substantial similarity of the hit song “Blurred Lines” to it amounted to copyright infringement. This issue – rather than the analyses of the copyright doctrines of idea/expression dichotomy or the merger doctrine – is what makes it problematic for innovations in the music industry because it essentially creates copyright ownership over a musical style.

We will not discuss the preliminary case facts in great detail since our earlier posting deals with the district court case.

The issues on appeal is whether there was substantial similarity between “Got to Give it Up” and “Blurred Lines,” written and produced by Pharrell Williams and sung by Robin Thicke (“Thicke defendants”), to amount to copyright infringement and thereby justify the lower court’s denial of motions for summary judgment and new trial. The 9th Circuit panel was composed of Judges Smith, Murguia, and Nguyen, with Judge Smith writing for the majority and Judge Nguyen writing in dissent. The majority focused on the procedural aspects of federal appellate litigation rules to dismiss the “Blurred Lines” arguments. In summary, the majority affirmed the district court’s rulings to deny the Thicke defendants’ motions for summary judgment as a matter of law and new trial, [2] but reversed on the motion for remittitur.[3] The panel noted that the Thicke defendants failed to file the proper motions according to the rules and there was nothing in the record to indicate an abuse of discretion by the district court in rendering its ruling.

We have decided this case on narrow grounds. Our conclusion turns on the procedural posture of the case, which requires us to review the relevant issues under deferential standard of review.[4]

The dissent focused more on copyright law, which will be the focus of this posting. Judge Nguyen opens her dissenting opinion with:

The majority allows the Gayes to accomplish what no one has before: copyright a musical style. “Blurred Lines” and “Got to Give It Up” are not objectively similar. They differ in melody, harmony, and rhythm. Yet by refusing to compare the two works, the majority establishes a dangerous precedent that strikes a devasting blow to future musicians and composers everywhere.[5]

It was an error by the majority to skip over the district court’s holding as to the copyright infringement. Judge Nguyen notes that the “purpose of copyright law is to ensure a robust public domain of creative works.”[6] Copyright protection also only protects the expression rather than the underlying idea.[7] This is known as the “idea/expression dichotomy,”[8] which aims to create a delicate balance between First Amendment principles and copyright law.[9] This restriction on free expression is allowed because “in art, there are, and can be, few, if any, things, which in an abstract sense, are strictly new and original throughout.”[10] Borrowing is necessary and especially in songwriting and musical works, it is necessary to “borrow others’ ideas and express them in new ways . . . [and disallowing this freedom] artists would cease producing new works – to society’s great detriment.”[11]

While it was undisputed that both “Got to Give It Up” and “Blurred Lines” shared the same groovy musical genre combination of funk, jazz, and R&B, this concept is an unprotected idea. Nevertheless, where musical compositions are involved, protected expression is primarily through melody, harmony, and rhythm.[12] Judge Nguyen then analyzed the two songs for their melodic, harmonic and rhythmic similarities. She looked at three main segments in the two songs – the signature phrase, the hook phrase, the Theme “X” – as well as other alleged similar aspects between the songs.

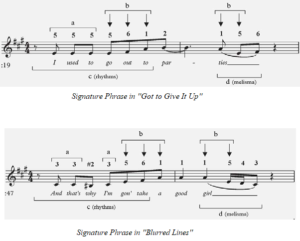

Signature Phrase

The Gayes’ expert testified that the signature phrase, or tune, is a is a 10-note segment in “Got to Give It Up” that corresponds to a 12-note segment in “Blurred Lines.” There were four similar elements: a) repeated notes at the beginning of the segment; b) three identical pitches in a row in the first measure and two in the second measure; c) same rhythm; and d) an ending melisma.[13]

The repeated nature of four notes in the Gaye song, and single note repeated twice, then a different note repeated once in the Thicke song are not substantially similar. Further, the use of repeating notes itself is not a copyright-protected expression. In addition, Judge Nguyen expressed that:

Even when each element is not individually protectable, “[t]he particular sequence in which an author strings a significant number of unprotectable elements can itself be a protectable element.”[14]

Judge Nguyen noted that there was little similarity between the two songs’ signature phrases. In both, the melodies rise and fall and different times, and each begins on different pitches. The highest and most recognizable pitch in the “Blurred Lines” signature phrase is consonant with the underlying harmony; in “Got to Give It Up,” it is dissonant. Further, the five identical pitches in the signature phrases do not line up rhythmically with each other. Harmonies change in “Blurred Lines,” but remain the same in “Got to Give It Up.” Finally, the lyrics are in different places.

Based on this, Judge Nguyen found no substantial similarity between the two signature phrases.

The most that can be said is that the two segments bear some relation to one another within the finite world of melodies.[15]

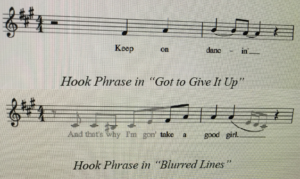

Hook Phrase

The hook phrase of a song is the catchy part of a song that draws in the listener. The Gayes’ expert testified that the hook phrase in “Got to Give It Up” is a four-melodic pitch segment sung to the lyrics “keep on dancin’.” The expert further testified that the two “Blurred Lines” hook phrase were similar to Gaye’s song. The first is the four pitch segment in the signature phrase sung to the lyrics “take a good girl,” while the second is a five pitch segment sung to the lyrics “I hate these blurred lines.”

Judge Nguyen took issue to this similarity. The “Blurred Lines” similarity is based on two different phrases in “Got to Give It Up,” one in the signature phrase and the other in the hook phrase, and taking a skeptical view, Judge Nguyen opined:

It is difficult to see how anything original in each of these two different phrases could be distilled into the same four-note phrase in “Blurred Lines.”[16]

Further, Judge Nguyen noted that the hook phrase only lasts 2.5 seconds and only contains four pitches. It is a very common technique used in other musical compositions. As such, it is not sufficient for originality required for copyright protection.

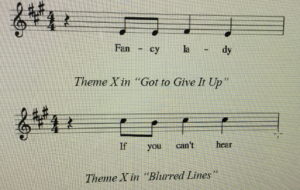

Theme X

The Theme X refers to a four-note melodic sequence. In “Got to Give It Up,” it is sung to the lyrics “Fancy lady.” In “Blurred Lines,” the Theme X is sung to the lyrics “If you can’t hear.” A Theme X is not protected by copyright based on originality. Judge Nguyen determined that the Theme X of both songs are dissimilar, based on pitch and rhythm, and the notes are completely different.

Other Similarities

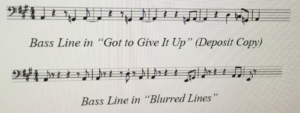

Judge Nguyen disagreed with the Gayes’ expert testified that the keyboard music (i.e., chords and rhythms played above the bass line) were very similar to each other. She noted that deposit copy of the Gaye song, as registered, contains no keyboard parts. Further, the bass line which is important backup musical aspects of both songs, is not sufficiently fixed in a tangible medium to warrant copyright protection.

In addition, the only similarity that Judge Nguyen could discern between the two songs is that they repeat the same note A in many of the measures. There are some differences in how the bass line is played, in that in the Gaye song, the note is syncopated to play before the downbeat, while in the Thicke song, the note is played on the downbeat.

Judge Nguyen further noted that both songs used two songwriting techniques, word painting and parlando, but neither are protected copyright expressions. Word painting is a compositional technique where music illustrates the lyrics, such as setting a word higher to an ascending melody. Parlando is spoken word or rap in the middle of a song. As such, there cannot be substantial similarity based on use of commonly used song devices.

Structurally, Judge Nguyen noted that there is a lack of structural similarity between the two songs. There is no chorus in “Got to Give It Up” while “Blurred Lines” is a typical pop song structure with a verse, pre-chorus, and chorus. The songs’ harmonies also share no same or similar chords.

Judge Nguyen, therefore, based on a substantial similarity analysis of the two songs, would have determined that the Thicke defendants were entitled to judgment as a matter of law. She criticized the majority’s lack of understanding the role of expert testimony in copyright infringement cases. Experts must testify as to factual relevance, and cannot “opine about legal conclusions.”[17]

This case may have a chilling effect on songwriters and music producers because it creates disputes, not on similarities of lyrics or music itself but, on an entire genre of music. Given the vigorous dissent from Judge Nguyen, it can be assumed that the Thicke defendants will pursue en banc review or even certiorari before the U.S. Supreme Court.

[1] ___F.3d___ (9th Cir. 2018), (15-56880), No. 2:13-cv-06004-JAK-AGR (9th Cir. Mar. 21, 2018).

[2] See F.R.C.P. Rule 50(a) and Rule 50(c).

[3] See F.R.C.P. Rule 59.

[4] See Williams, supra (slip op. at 56).

[5] Id. (slip op at 57) (Nguyen, J., dissenting).

[6] See Sony Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417, 429 (1984).

[7] See 17 U.S.C. §102(a).

[8] See generally Edward Samuels, The Idea-Expression Dichotomy in Copyright Law, 56 Tenn. L. Rev. 321 (1989).

[9] See Bikram’s Yoga Coll. of India, L.P. v. Evolation Yoga, LLC, 803 F.3d 1032, 1038-39 (9th Cir. 2015) (holding that Bikram yoga sequences are not protected under copyright law).

[10] See Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 575 (1994).

[11] Williams, supra (slip op. at 60-61) (Nguyen, J., dissenting).

[12] See Newton v. Diamond, 204 F. Supp. 2d 1244, 1249 (C.D. Cal. 2002) (citing 3 Melvin D. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright, §2.05[D] (rev. 2017)).

[13] “Melisma” is a musical technique where a group of notes of a song are sung on one syllable of song text.

[14] Williams, supra (slip op. at 71) (Nguyen, J., dissenting).

[15] Id. (slip op. at 72) (Nguyen, J., dissenting) (citing Johnson v. Gordon, 409 F.3d 12, 22 (1st Cir. 2005).

[16] Id. (slip op. at 73) (Nguyen, J., dissenting)

[17] Id. (slip op. at 82) (Nguyen, J., dissenting).