Fed Circuit Watch: Common Sense Cannot Replace Evidentiary Support

On March 23, 2018, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed down DSS Techs. Mgmt., Inc. v. Apple Inc.,1 reversing two IPR decisions in Apple’s favor on a DSS-owned patent which the PTAB ruled as unpatentable as obvious. The Fed Circuit panel went to lengths to call out the PTAB’s poor analysis and evidentiary support for its finding of obviousness. There was also a vigorous dissent.

The facts are as follows.

DSS owns U.S. Patent No. 6,128,290 (‘290),2 directed to wireless communications network system for a single host and peripheral devices. Claim 1 was deemed representative:

A data network system for effecting coordinated operation of a plurality of electronic devices, said system comprising:

a server microcomputer unit;

a plurality of peripheral units which are battery powered and portable, which provide either input information from the user or output information to the user, and which are adapted to operate within short range of said server unit;

said server microcomputer incorporating an RF transmitter for sending commands and synchronizing information to said peripheral units;

said peripheral units each including an RF receiver for detecting said commands and synchronizing information and including also an RF transmitter for sending input information from the user to said server microcomputer;

said server microcomputer including a receiver for receiving input information transmitted from said peripheral units;

said server and peripheral transmitters being energized in low duty cycle RF bursts at intervals determined by a code sequence which is timed in relation to said synchronizing information.

(Emphasis added.)

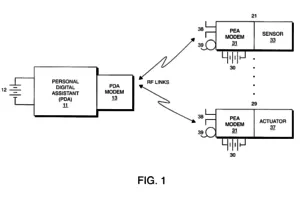

The written description discloses a “bidirectional wireless data communications between a host or server microcomputer – i.e., a PDA – and a plurality of peripheral devices that the specification refers to as ‘personal electronic accessories (“PEAs”).”3 Figure 1 depicts this invention:

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,128,290, October 3, 2000, to Philip P. Carvey

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,128,290, October 3, 2000, to Philip P. Carvey

The limitation in dispute is italicized. Specifically, both server and peripheral transmitting devices must be used in low duty cycle RF bursts, which is the subject of the IPRs.

Apple filed the two IPRs, introducing U.S. Patent No. 5,241,542 (“Natarajan”) to support a finding of unpatentability based on obviousness. The Natarajan reference is directed to power conservation in mobile unit communication. Similar to the DSS system, the Natarajan patent disclosed that it could reduce power when not in transmission or receipt of data.

Apple argued that “because the mobile unit transmitters in Natarajan operated in low duty cycle RF bursts, it would have been plainly obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art to have the base station operate in an analogous manner.” Further, because the mobile and base stations have similar structures, its operation would just be a known technique to improve the same or similar device in the same way.4

DSS countered with the argument that the Natarajan reference mentions nothing of reducing power consumption in the base station transmitter.

The PTAB agreed with Apple’s argument:

Natarajan is expressly concerned with “power conservation due to wireless communication,” and specifically, with “battery efficient operation of wireless link adapters of mobile computers as controlled by multiaccess protocols used in wireless communication.”5

Further, the PTAB noted that a person of ordinary skill (i.e., POSITA) would have been motivated by Natarajan to apply the same power-conservation technique from base units to mobile devices. Additionally, the PTAB found no persuasive evidence of record that it was challenging or difficult to a POSITA to be so motivated to combine.6 The PTAB emphasized that a POSITA is one of “ordinary creativity, and not an automaton.”7

The Fed Circuit panel, composed of Judges O’Malley, Newman, and Reyna, with Judge O’Malley writing for the majority, first observed that case precedent determined that “ordinary creativity” and “common sense” were the same concept, and noted “common sense and common knowledge have their proper place in the obviousness inquiry … if explained with sufficient reasoning.”8 There are three caveats to applying common sense to the obviousness analysis:

First, common sense is typically invoked to provide a known motivation to combine, not to supply a missing claim limitation… . Second, we have invoked common sense to fill in a missing limitation only when the limitation in question was unusually simple and the technology particularly straightforward … . Third, our cases repeatedly warn that references to ‘common sense’—whether to supply a motivation to combine or a missing limitation—cannot be used as a wholesale substitute for reasoned analysis and evidentiary support, especially when dealing with a limitation missing from the prior art references specified. 9

Based on Arendi, the panel found the PTAB’s analysis completely devoid of proper support for its obviousness finding.

After acknowledging that Natarajan does not disclose a base unit transmitter that uses the same power conservation technique, the Board concluded that a person of ordinary skill would have been motivated to modify Natarajan to incorporate such a technique into a base unit transmitter and that such a modification would have been within the skill of the ordinarily skilled artisan. In reaching these conclusions, the Board made no further citation to the record. It referred instead to the “ordinary creativity” of the skilled artisan. This is not enough to satisfy the Arendi standard.10

Judge Newman wrote the dissent. She had two concerns. First, she believed the PTAB had adequate support for its obviousness decision, basing its decision on arguments by the parties (specifically, Apple’s), the extrinsic evidence proffered by Apple’s expert witness, and the Natarajan reference itself. Second, she felt reversal was the improper judicial remedy for an inadequate support finding; she would rather have vacated and remanded for further proceedings.

This is a win for a non-practicing entity (NPE), although in this particular case, DSS is not strictly a patent litigator since it appears it has a healthy core business in cybersecurity. Nevertheless, the fact a patent troll is involved in this case does not absolve the PTAB’s responsibility to procure well-analyzed decisions based on proper evidentiary support, including the file history and case precedent. This has been a somewhat recurring theme, with the Fed Circuit handing down stern rulings against derisive PTAB decision-making that defy logic and legal analysis.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018), rev’g Apple Inc. v. DSS Tech. Mgmt., Inc., No. IPR2015-00369, 2016 WL 3382361 (PTAB Jun. 17, 2016), and rev’g Apple Inc. v. DSS Tech Mgmt., Inc., No. IPR2015-00373, 2016 WL 3382464 (PTAB Jun. 17, 2016). ↩

-

The ‘290 patent, originally filed October 14, 1997, was subject to a terminal disclaimer, and expired on March 6, 2016. ↩

-

See DSS, supra (slip op. at 2). ↩

-

See MPEP 2143, one of the exemplary rationales for sustaining a prima facie case of obviousness is “use of known technique to improve similar device (method or product) in the same way.” ↩

-

See DSS, supra (slip op. at 9). ↩

-

See KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 420-21 (2007). ↩

-

See DSS, supra (slip op. at 11) (citing Arendi S.A.R.L. v. Apple Inc., 832 F.3d 1355, 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2016)). ↩

-

See Arendi, 832 F.3d at 1361-62. ↩

-

See DSS, supra (slip op. at 13). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent