In a potentially ground-breaking decision in design patent prosecution, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed down In re Maatita,[1] on August 20, 2018.

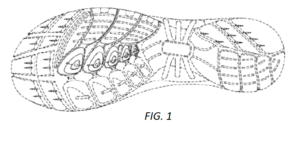

The facts are as follows. Ron Maatita filed a design patent application with the USPTO, Serial No. 29/404,677, claiming an athletic shoe sole design.

As with all design patent applications, the single claim recited: “The ornamental design for a Shoe Bottom as shown and described,” (MPEP 1503.01) and included two drawing figures showing the claimed shoe sole. Typical with design patent drawings, solid lines depict the claimed invention, while broken lines show those parts of the design that is unclaimed. The examiner rejected the invention, stating that the claim failed to satisfy the enablement and definiteness requirements under 35 U.S.C. §112, first and second paragraphs (now §112(a)-(b)), asserting that the shoe sole was a three-dimensional object for which the two-dimensional drawing left open to interpretation as to the sole’s depth and contour of the claimed elements, thus making the invention unenabled and indefinite. The PTAB affirmed.

The Fed Circuit panel, composed of Judges Dyk, Reyna, and Stoll, with Judge Dyk writing for a unanimous court, disagreed.

The enablement requirement under §112(a) states:

The specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the same.

The definiteness requirement under §112(b) states:

The specification shall conclude with one or more claims particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter which the applicant regards as his invention.

Judge Dyk explained that with design patents, the claims are limited to what is shown in the drawings, and as such, both enablement and definiteness can be analyzed together (MPEP 1504.04(I)(A)). He further explained that for the definiteness requirement under §112(b), not all depth positions are required to be shown; the POSITA already can discern the claimed invention from the two-dimensional showing of the invention (in this case, the two drawings).

The government is correct that a shoe sole is typically three-dimensional, with treads that may be convex or concave. And, indeed, many shoe bottom designers choose to claim their designs in a three dimensional fashion. But the fact that shoe bottoms can have three-dimensional aspects does not change the fact that their ornamental design is capable of being disclosed and judged from two-dimensional, plan- or planar-view perspective – and that Maatita’s two-dimensional drawing clearly demonstrates the perspective from which the shoe bottom should be viewed.[2]

For either an enablement or definiteness analysis, inconsistencies in the drawings, by themselves, do not merit a §112 rejection if the inconsistencies “do not preclude an understanding of the drawing as a whole.”[3] Therefore, a design patent is indefinite if a POSITA, when viewing the design, would not understand the scope of the design based on the drawings. The panel was guided by the Nautilus decision that a claim is indefinite if the claim fails to inform to a reasonable certainty to a POSITA about the scope of the invention.[4] Claim scope, not inconsistency, was the issue in this case. As Judge Dyk noted, the purpose of §112 is to serve notice on would-be infringers what design is being claimed, and presumably what would be infringed.

So long as the scope of the invention is clear with reasonable certainty to an ordinary observer, a design patent can disclose multiple embodiments within its single claim and can use multiple drawings to do so.[5]

In so doing, Judge Dyk has, perhaps unwittingly, opened flung wide-open the breadth of design patent claims with this opinion. Design patent applicants can now have freedom to operate by claiming potentially unrecognized depth through unspecified contours and concavities. Judge Dyke did raise the doubt a potential infringer would face when assessing its product as infringing. However, he was unconvinced that this was an issue.

A potential infringer is not left in doubt as to how to determine infringement. In this case, Maatita’s decision not to disclose all possible depth choices would not preclude an ordinary observer (i.e., POSITA) from understanding the claimed design, since the design is capable of being understood from the two-dimensional plan.[6]

The problem here lies with the factors for enablement, which include 1) breadth of claims, 2) nature of invention, 3) state of prior art, 4) level of ordinary skill (i.e., POSITA), 5) level of predictability in art, 6) amount of direction provided by inventor, 6) working examples, and 8) quantity of experimentation needed to make and use invention based on disclosure (MPEP 2164.01(a)). Maatita implicates 1), 4), 5), 6) and 8) of these factors.

Given the vastness of the §112(a) analysis on design patent prosecution handed down in this opinion, expect the USPTO to petition for en banc review and/or petition for writ of certiorari before the U.S. Supreme Court.

[1] ___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), rev’g Ser. No. 29,404,677,

[2] See Maatita, supra (slip op. at 13).

[3] See Ex Parte Asano, 201 U.S.P.Q. 315, 317 (B.P.A.I. 1978).

[4] See Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2120, 2124 (2014).

[5] See Maatita, supra (slip op. at 10).

[6] Id. (slip op. at 13).