An interesting study in organic chemistry appeared at the Federal Circuit. On April 16, 2018, a Fed Circuit panel in Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd. v. Emcure Pharm. Ltd.,[1] held that plain claim language will be construed narrowly absent the patentee’s clear disclaimer limiting its scope.

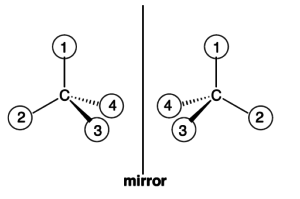

First a primer on stereochemistry, which is the study of a molecule’s three-dimensional structure. Stereoisomers are molecules with the same chemical formula and structure but with a different three-dimensional configuration. Enantiomers are two stereoisomers that are mirror images of each other. Enantiomers have identical physical properties, but different pharmacological properties and therefore can be useful in new drug compositions. Characterizations of enantiomers are depicted as “(+)” or “(–)” based on its optical activity – or the ability of an enantiomer in solution to rotate polarized light. Mixtures can contain enantiomers with different ratios. A 50% (+)-enantiomer/50% (–)-enantiomer is known as a “racemate” or “racemic mixture.” These enantiomers do not rotate because the (+) cancels out the (–).

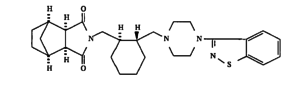

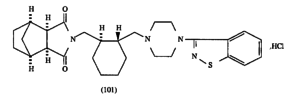

Sumitomo owns U.S. Patent No. 5,532,372 (‘372), directed to novel imide compounds and their acid addition salts. These compounds are useful in antipsychotic agents. Lurasidone, a (–)-enantiomer covered in the ‘372 patent, is the active ingredient in Sumitomo’s LATUDA® drug to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The ‘372 teaches several different embodiments, including the Compound 101 synthesis:

Compound 101 is chiral because it contains a cyclohexyl (i.e., a cyclic hydrocarbon radical, or C6H11) linker.

Compound 101 is chiral because it contains a cyclohexyl (i.e., a cyclic hydrocarbon radical, or C6H11) linker.

Emcure filed an ANDA application to market a generic of LATUDA®. Sumitomo then filed a patent infringement suit against Emcure. The claim at-issue on appeal is claim 14 of the ‘372 patent:

14. The imide compound of the formula:

or an acid addition salt thereof.

The claimed imide compound is similar to Compound 101 because it is also chiral with a cyclohexyl linker. Both parties stipulated that the three-dimensional figure in claim 14 is lurasidone, the (–)-enantiomer.

The issue was what enantiomers were covered by claim 14. Emcure argued that claim 14 was limited to a racemic mixture of two enantiomers. For support, Emcure relied on the Compound 101, and introduced extrinsic evidence in the form of organic chemistry textbooks. The district court rejected the argument, because such a limitation was not supported by the intrinsic evidence, namely the specification.[2] Emcure then appealed the district court’s claim construction order.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges Moore, Mayer, and Stoll, with Judge Stoll writing for the court. Claim construction ascribes the “ordinary and customary meaning” to a claim term as a POSITA would have understood it at the time of the invention.[3] Further, the ordinary and customary meaning controls unless the patentee sets out his own lexicography, or disavows the claim term’s scope in the specification or during prosecution.[4]

Judge Stoll noted that the plain claim language and the specification both show that claim 14 covers a (–)-enantiomer, as the parties had both stipulated. She further noted that the specification actually confirms the plain and ordinary meaning of claim 14 because rather than excluding the (–)-enantiomer, the specification describes it as a preferred embodiment. Further, the claimed imide compound has 4 isomers: R-trans, S-trans, R-cis, and S-cis.[5] Sumitomo specifically disclaimed the R-cis and S-cis enantiomers in the specification, but not the R-trans and S-trans isomers. Additionally, there was no applicant disavowal of the patent’s scope to just a trans racemate. The panel therefore construed the claim to cover R- and S-trans enantiomers, as well as any mixtures of the two trans isomers. She concluded:

To act as a lexicographer, the patentee must “clearly set forth a definition of the disputed claim term. Here, the ‘372 patent does not define the structure in claim 14 as a racemate or as coextensive with Compound No. 101. Claim 14 does not refer to Compound No. 11, and nothing in the specification links to two structures together. This is not enough to restrict a claim’s scope.[6]

The panel, therefore, affirmed the district court’s claim construction of claim 14.

[1] ___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018), aff’g Case No. CV 15-280, 2016 WL 6803077 (D.N.J. Nov. 15, 2016).

[2] See MPEP 2111: “. . . claims must be given their broadest reasonable interpretation consistent with the specification.”

[3] See Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1312-14 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc).

[4] See Thorner v. Sony Comput. Entm’t Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2012). See also MPEP 2111.01 (“the words of a claim must be given their ‘plain meaning’ unless such meaning is inconsistent with the specification” and “applicant may be own lexicographer and/or may disavow claim scope.”).

[5] “R” and “S” nomenclature is a different way of terming two enantiomers; “cis” describes the substituents as on the same side of a carbon chain, while “trans” describes the substituents oriented in opposite directions.

[6] See Sumitomo, supra (slip op. at 11).