This is the second case dealing with Novartis in which the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has handed down a decision related to patent term. While the facts of this case, Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC,[1] are very similar to the companion case decided on the same day, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. v. Breckenridge Pharmaceuticals Inc., for which we have just discussed recently on this blog, the court’s ruling dealt specifically with a very narrow issue, namely whether the judicially-created doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting (ODP) precludes a patent term extension under 35 U.S.C. §156.

Novartis owns U.S. Patent Nos. 5,604,229 (‘229) and 6,004,565 (‘565). The ‘229 patent is directed to, among others, the compound fingolimod, the active ingredient in the multiple sclerosis drug, GILENYA®. The ‘565 patent is directed to a method of administering fingolimod.

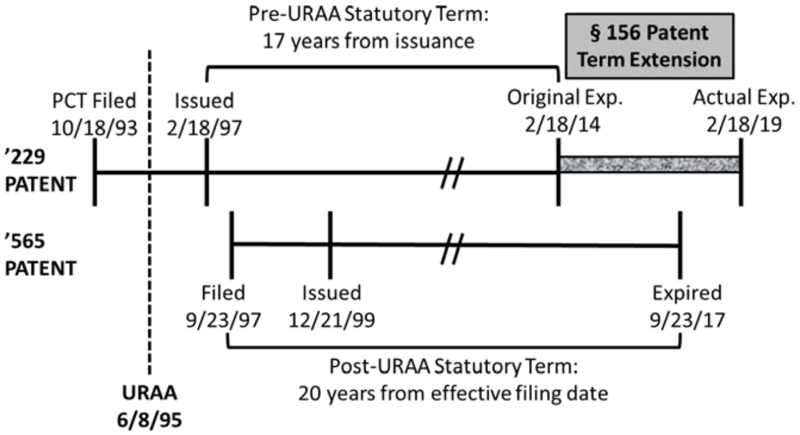

Patent term has changed based on acts of Congress. Prior to June 8, 1995, patent term was 17 years from the issue date. The Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URAA) extended patent term to 20 years from effective filing date, which applied to patent applications filed on or after June 8, 1995 (35 U.S.C. §154(c)(1)). Patent term extension (PTE) under §156 allow certain pharmaceutical patents to be extended beyond its patent term to a maximum of five years upon petition’s grant. The ‘229 patent is a pre-URAA patent that expired 17 years from its issuance, or February 18, 2014. The ‘565 patent is a post-URAA patent that was filed September 23, 1997, and expired on September 23, 2017. Of the two patents, Novartis chose the ‘229 patent for §156(a) patent term extension eligibility. The ‘229 petition, therefore, with the extension, expired on February 18, 2019.

The specifics of the two patents’ lifespans, vis-à-vis §156, is shown below:

Novartis sued Ezra for patent infringement of claims 9, 10, 35, 36, 46, and 48 of the ‘229 patent in the District of Delaware when Ezra sought an ANDA application for a generic of Gilenya. Ezra had argued that 1) the ‘229 patent should be invalidated because the PTE qualified as an impermissible extension of the ‘565’s patent term in violation of §154(c)(4)’s requirement that only one patent be extended; 2) that the ‘229 term extension upsets the prevailing public policy for expired patents to enter the public domain; and 3) that the ‘229 patent is further invalidated under obviousness-type double patenting (ODP) (MPEP 1504.06)[2] because its claims are not patentably distinct from the ‘565 patent. ODP is a judicially-created doctrine with the intent to prevent artificially extending a patent term through claims of a second, related patent that are not patentably distinct from the claims in the first patent (MPEP 804).

Relying primarily on the Fed Circuit’s Merck precedent holding that a terminally disclaimed patent could still be eligible for patent term extension because:

Congress chose not to limit the availability of a patent term extension to a specific parent or continuation patent but instead chose a flexible approach which gave the patentee the choice.[3]

The district court further held that “expiration of a patent does not grant the public an affirmative right to practice a patent; it merely ends the term of the patentee’s right to exclude others from practicing the patent.”[4] To underline this point, the district court noted that Ezra had not provided authority for its policy position. The district subsequently dismissed Ezra’s Rule 12(c) motion. Ezra appealed the decision.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges Moore, Chen, and Hughes, with Judge Chen writing for the court (who also wrote the opinion in the Breckenridge case). Concerning Ezra’s contention that the ‘229 “effectively” extended the ‘565 patent’s term, therefore, violating §154(c)(4), Judge Chen dismissed this argument, stating:

[T]here is no reason to read “effectively” as a modifier to “extend” in the language of §154(c)(4). As a basic principle of statutory construction, courts ordinarily resist reading words into a statute that do not appear on its face.

As a result, Judge Chen concluded that Novartis’ use of the ‘229 patent did not violate §154(c)(4).

As to Ezra’s ODP argument, he noted:

the contrast between §156 for PTE with the language of §154 for patent term adjustments: §154 expressly excludes patents in which a terminal disclaimer was filed from the benefit of a term adjustment for PTO delays, but §156 contains no similar provision that excludes patents in which a terminal disclaimer was filed from the benefits of Hatch-Waxman extensions[5] . . . . The express prohibition against a term adjustment regarding PTO delays under §154(b), the absence of any such prohibition regarding Hatch-Waxman extensions, and the mandate in §156 that the patent term shall be extended if the requirements enumerated in that section are met, support the conclusion that a patent term extension under §156 is not foreclosed by a terminal disclaimer.

In practice, during prosecution, if two patent claims are patentably indistinct, the later-expiring patent is required to have a terminal disclaimer under 35 U.S.C. §253 filed to obviate the ODP rejection by the Examiner. The ‘565 patent never had a terminal disclaimer filed during prosecution, and Ezra had attempted, unsuccessfully, to use that to buttress its ODP argument. Judge Chen, therefore, concluded that if a patent under its pre-PTE expiration date is valid under all other patent law provisions, it is entitled to the full term of the PTE.

As to Ezra’s policy concern, Judge Chen shot this argument down with a curt statement:

This case also does not present the concerns that drove recent decisions of this court regarding obviousness-type double patenting in the post-URAA context. There is no potential gamesmanship issue through structuring of priority claims as identified in Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd.[6] Gilead recognized a situation where inventors could routinely orchestrate longer patent-exclusivity periods by (1) filing serial patent applications on obvious modifications of an invention, and (2) claiming different priority dates in each, and then (3) strategically responding to prosecution deadlines such that the application claiming the latest filing date issues first, without triggering a terminal disclaimer for the earlier filed application . . . . Here, Ezra does not identify any similar tactics on the part of Novartis . . . [A]greeing with Ezra would mean that a judge-made doctrine [ODP] would cut off a statutorily-authorized time extension. We decline to do so.

For these reasons, the Fed Circuit affirmed that the district court judgment.

[1] ___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), aff’g 2016 WL 5334464 (D. Del. 2016).

[2] This is contrasted with statutory double patenting under 35 U.S.C. §101, which prevents two patents from issuing on the same invention; see also Takeda Pharm. Co. v. Doll, 561 F.3d 1372, 1375 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

[3] See Merck & Co., Inc. v. Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co., Inc., 482 F.3d 1317, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

[4] Id.

[5] Id. at 1322.

[6] 753 F.3d 1208, 1211-12, 1214 (Fed. Cir. 2014).