Understanding Section 101 Patent Subject-Matter Eligibility

Section 101 of the Patent Act,1 establishes the foundation for what constitutes patentable subject matter in the United States. The seemingly straightforward language – “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor” – has generated decades of complex jurisprudence that continues to shape the modern patent landscape.

Historical Foundation

The journey of Section 101 interpretation began with early Supreme Court precedents that established broad categories of unpatentable subject matter. The Court’s 1972 decision in [Gottschalk v. Benson](http://409 U.S. 63 (1972)),2 marked the beginning of modern abstract idea jurisprudence by holding that mathematical algorithms, standing alone, are not patentable. This was followed by Parker v. Flook,3 which refined the analysis by focusing on whether the claimed invention as a whole contained patentable subject matter beyond the abstract concept.

The pendulum swung toward greater patent eligibility in Diamond v. Chakrabarty,4 where the Supreme Court famously declared that patents may cover “anything under the sun that is made by man.” However, the Court simultaneously reinforced the fundamental exclusions for “laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas.”

The Modern Framework Emerges

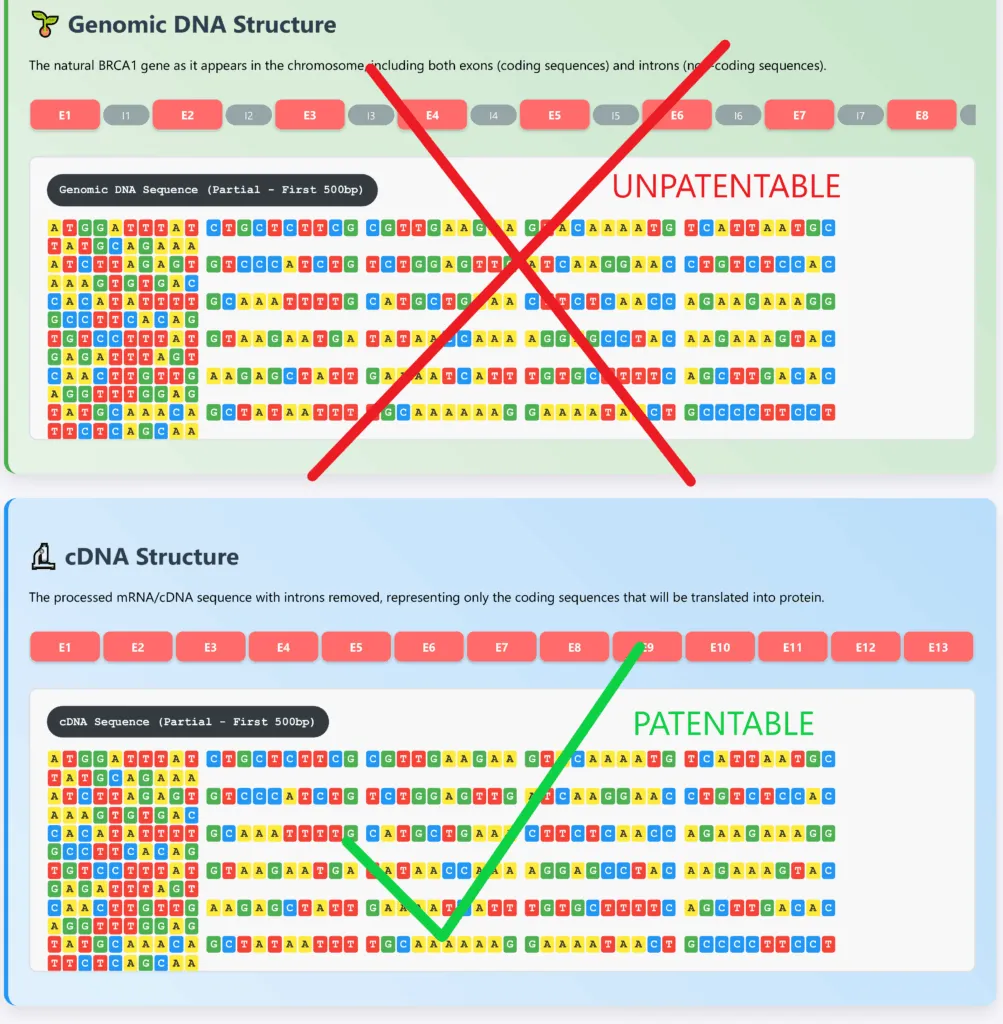

The naturally-occurring DNA sequence of the BRCA1 gene was held not patent-eligible, but the cDNA sequence was in Myriad Genetics.

The naturally-occurring DNA sequence of the BRCA1 gene was held not patent-eligible, but the cDNA sequence was in Myriad Genetics.

The contemporary framework for Section 101 analysis began with the Supreme Court’s decision in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories,5 in which the Court held diagnostic claims were directed to a patent-ineligible inventive concept. In Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc.,6 The Court held that the BRCA1 gene, although discovered and isolated from the body, was a naturally-occuring organism and not patent-eligible. However, the bio-engineered complementary DNA sequence of the genetic code was patent-eligible. This framework was reinforced and expanded in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International,7 which applied Mayo/Myriad to business method patents and established that implementing an abstract idea on a generic computer does not automatically confer patent eligibility. Alice established a two-step test that has become the cornerstone of patent eligibility analysis:

-

Step 1: Determine whether the claims are directed to a patent-ineligible concept (laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas).

-

Step 2: If so, examine whether the claim contains an “inventive concept”—additional elements that transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application.

The Federal Circuit’s Struggle with Mayo/Alice Framework

Following Alice, the Federal Circuit has grappled with consistent application of the Mayo/Alice framework, particularly in the realm of software and business method patents. Cases like Enfish LLC v. Microsoft Corp.,8 provided some hope for software patents by finding that claims directed to improving computer functionality could survive Step 1 analysis. Similarly, McRO Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America Inc.,9 showed that specific technological improvements could overcome abstract idea rejections.

However, other Federal Circuit decisions have been less favorable to patent holders. Certain cases demonstrated the court’s willingness to find patents invalid under Section 101, even when they involved complex technological systems. In Recentive Analytics, Inc. v. Fox Corp.,10 Recentive’s claims were held patent-ineligible abstract ideas directed to using a generic machine learning technique with no inventive concept. In Optis Cellular Technology, Inc. v. Apple Inc.,11 claims of the Optis ‘332 patent were directed to an abstract mathematical formula. And, in United Services Automobile Association v. PNC Bank, N.A.,12 the Federal Circuit held that claims reciting routine data collection traditionally performed as a bank function, and performed through a mobile device, still did not rise above being merely an abstract idea.

The Continuing Evolution

The patent eligibility landscape remains in flux, with the Federal Circuit continuing to refine its approach to the Mayo/Alice test. Recent decisions have shown particular scrutiny of patents claiming to solve business problems using conventional computer technology, while demonstrating more receptivity to claims that purport to solve technological problems with specific technical solutions.

The USPTO has attempted to provide guidance through various memoranda and examination guidelines, but the inherently fact-specific nature of Section 101 analysis continues to create uncertainty for patent applicants and holders alike.

Conclusion

Section 101 jurisprudence continues to evolve as courts balance the constitutional mandate to promote innovation with the need to prevent the patenting of fundamental concepts. The ongoing tension between encouraging technological advancement and preventing the overreach of patent protection ensures that Section 101 will remain a dynamic and closely watched area of patent law.

As we move forward, practitioners and inventors must navigate this complex landscape with careful attention to both the broad Supreme Court principles and the nuanced interpretations of the Federal Circuit. The state of patent eligibility remains a landscape pockmarked with legal landmines, especially for software and computer-focused claims. Patent applicants must engage very thoughtful patent drafters and employ distinct prosecution strategies for handling §101 rejections.

For more information, please contact Yonaxis I.P. Law Group.

Footnotes

-

35 U.S.C. §101. ↩

-

409 U.S. 63 (1972). ↩

-

437 U.S. 584 (1978). ↩

-

447 U.S. 303 (1980). ↩

-

566 U.S. 66 (2012). ↩

-

569 U.S. 576 (2013). ↩

-

573 U.S. 208 (2014). ↩

-

822 F.3d 1327, 1335-36 (Fed. Cir. 2016). ↩

-

837 F.3d 1299, 1316 (Fed. Cir. 2016). ↩

-

134 F.4th 1205, 1215 (Fed. Cir. 2025). ↩

-

___F.4th___, Case Nos. 22-1904, 22-1925, at *24-25 (Fed. Cir. June 16, 2025). ↩

-

Case No. 2023-1639, at *8 (Fed. Cir. June 12, 2025) [non-precedential]. ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent