Understanding the Elements of a Copyright Infringement Claim

Copyright cases require plaintiffs to prove specific elements to establish a valid claim. Understanding these requirements is necessary for both copyright holders seeking to protect their work and defendants facing allegedly infringing allegations. This post examines the fundamental elements of copyright infringement, focusing on the analysis of the copying requirement. Because the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit is one of the two largest copyright-case law-producing circuits (the other is the Second Circuit, based in New York), this posting will analyze the case law as developed by the Ninth Circuit’s jurisprudence. A case study is also illustrated through the recent Woodland v. Hill case involving photographer Rodney Woodland and rapper Lil Nas X.

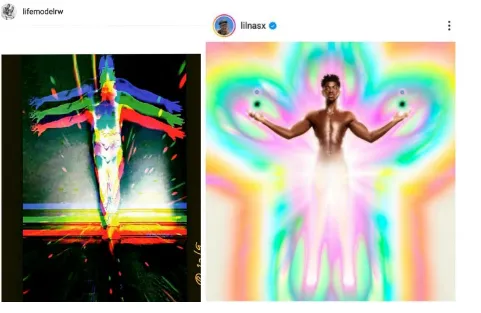

Woodland’s photo left; Hill’s photo right (Source: Ninth Circuit opinion)

Woodland’s photo left; Hill’s photo right (Source: Ninth Circuit opinion)

Elements of Copyright Infringement

To succeed in a copyright infringement claim, 17 U.S.C. §501 a plaintiff must establish two primary elements:

- Valid copyright ownership

- Copying of elements of the plaintiff’s work by the defendant

While ownership may seem straightforward, the copying element presents more complex legal challenges, particularly in the Ninth Circuit’s jurisdiction.

Element One: Ownership

The ownership requirement mandates that the plaintiff demonstrate they hold a valid copyright in the allegedly infringed work. This typically involves showing that the work is original, fixed in a tangible medium of expression, and contains at least a minimal degree of creativity. For registered copyrights, a certificate of registration creates a presumption of validity, though this presumption can be rebutted.

Courts have consistently held that copyright protection extends only to the expression of ideas, not the ideas themselves.1 This distinction becomes particularly important in cases involving similar artistic concepts or compositions, as seen in photography and visual arts.

Element Two: Copying

The Ninth Circuit has developed a distinctive two-pronged approach to analyzing the copying element, requiring plaintiffs to prove both copying and unlawful appropriation.2

Prong One: Copying

The first prong requires evidence that the defendant actually copied the plaintiff’s work. Since direct evidence of copying is rarely available, courts typically allow plaintiffs to establish copying through circumstantial evidence by showing:

- Access: The defendant had a reasonable opportunity to view or hear the plaintiff’s work.

- Probative similarity: The works share similarities that are probative of copying.

The access requirement has evolved significantly in the digital age. In Three Boys Music Corp. v. Bolton,3 the Ninth Circuit established that widespread dissemination of a work can satisfy the access requirement. However, as demonstrated in recent cases, mere posting on social media platforms does not automatically establish access, particularly when the original work received limited engagement or visibility.

Prong Two: Unlawful Appropriation

After copying is established, the plaintiff must also prove that the copying constitutes “unlawful appropriation.” This requires showing that the defendant copied protected expression, not merely unprotectable ideas or elements. The court applies the “ordinary observer” test, asking whether an ordinary observer would recognize the defendant’s work as having been appropriated from the plaintiff’s copyrighted work.

In Sid & Marty Krofft Television Productions, Inc. v. McDonald’s Corp.,4 the Ninth Circuit emphasized that unlawful appropriation requires copying of the work’s “expression,” focusing on the specific way ideas are manifested rather than the underlying concepts themselves.

Case Study: Woodland v. Hill

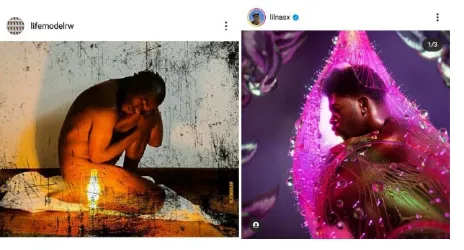

Woodland’s photo left; Hill’s photo right (Source)

Woodland’s photo left; Hill’s photo right (Source)

The recent Woodland v. Hill5 decision from the Ninth Circuit illustrates these elemental aspects, particularly in the social media context.

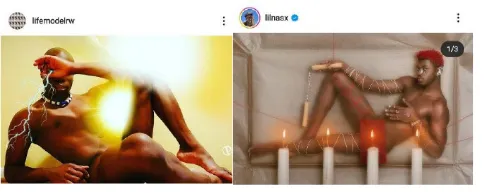

Woodland’s photo left; Hill’s photo right (Source)

Woodland’s photo left; Hill’s photo right (Source)

Rodney Woodland, a photographer, sued Montero Lamar Hill, professionally known as Lil Nas X, for copyright infringement. Woodland claimed that Hill posted photos on his Instagram page that were too similar to photos Woodland had posted on his own Instagram account. The case involved photographs posted by Woodland between August 2018 and July 2021, which received relatively modest engagement (eight to seventy-five “likes”), compared to Hill’s allegedly similar photos posted between March and October 2021, which garnered hundreds of thousands to millions of “likes.”

The Ninth Circuit’s analyzes both prongs of the copying element:

Woodland’s photo left; Hill’s photo right (Source)

Woodland’s photo left; Hill’s photo right (Source)

Access: the Ninth Circuit held that Woodland did not plausibly allege that Hill had “access” to Woodland’s photos, because the mere fact that Woodland posted his photos on Instagram was insufficient to show that Hill had viewed them. Woodland clarifies that in the digital context, simply posting content on a social media platform does not automatically establish access, particularly when the original content received limited visibility compared to the defendant’s massive social media following.

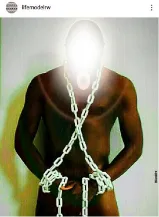

Woodland’s photo (Source)

Woodland’s photo (Source)

Unlawful Appropriation: the court found that Woodland failed to prove the second prong. The court explained that the Copyright Act protects only the selection and arrangement of individual elements (i.e., subject’s poses) in a photo, and the photos in question were not substantially similar in their selection and arrangement of these poses. Woodland focused his arguments on claiming a copyright interest in certain elements in isolation, and this is not consistent with the selection-arrangement doctrine. The Woodland decision demonstrates how courts focus on specific expressive elements rather than general concepts or “ideas.”

Hill’s photo (Source)

Hill’s photo (Source)

Legal Implications

The Woodland decision reinforces several important principles:

- Access in Social Media: Mere availability of content online, without more, does not establish the access necessary for copying. Courts require evidence of a reasonable probability that the defendant actually encountered the plaintiff’s work.

- Substantial Similarity in Photography: The decision clarifies that copyright protection in photographs extends only to the specific selection and arrangement of elements, not to general poses, concepts, or artistic styles that might be considered unprotectable ideas.

Takeaways

- For Copyright Owners: Establishing access requires more than showing that content was publicly available. Plaintiffs should gather evidence of actual viewing, engagement, or other indicators that the defendant likely encountered the copyrighted work. Additionally, claims must focus on specific expressive elements rather than general concepts or ideas.

- For Creators: Defending a copyright infringement suit provides multiple opportunities to challenge copying claims. Defendants can contest access by arguing no reasonable opportunity to view the work and unlawful appropriation by arguing that any similarities relate to unprotectable elements.

Conclusion

Federal law through the Copyright Act protects creative endeavors. However, prosecuting a copyright infringement case is not easy. Establishing proof of each element requires extensive evidence-gathering and a careful litigation strategy. Potential copyright plaintiffs should engage with experienced I.P. litigation attorneys when pursuing litigation.

For more information on a copyright infringement claim, copyright law, or intellectual property law in general, please contact Yonaxis I.P. Law Group.

Footnotes

-

See Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340, 361 (1991). ↩

-

See Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin, 952 F.3d 1051, 1064 (9th cir. 2020) (en banc); Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc., 883 F.3d 1111, 1117 (9th Cir. 2018). ↩

-

212 F.3d 477, 482 (9th Cir. 2000). ↩

-

562 F.2d 1157 (9th Cir. 1977). ↩

-

___4th___, 23-55418 (9th Cir. May 16, 2025). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent