Prosecution History Estoppel Limits Design Patent Amendments

A fascinating ruling dealing with design patents, amendments made during prosecution, and limitations on claim scope was handed down by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on September 12, 2019 in Curver Luxembourg, Sarl v. Home Expressions Inc..1 Curver is an important piece in an otherwise scant design patent case law.

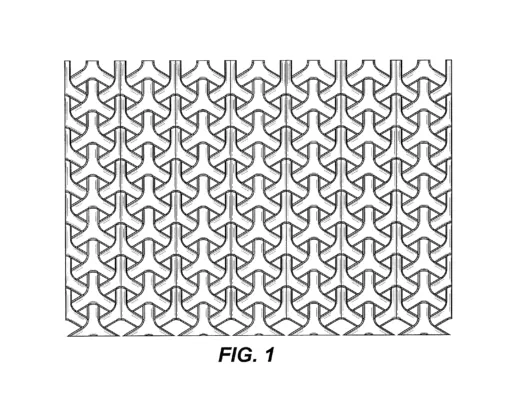

Source: U.S. Patent No. D677,946, Mar. 19, 2013, Nikolai Duvigneau (inventor); Curver Luxembourg Sarl (assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent No. D677,946, Mar. 19, 2013, Nikolai Duvigneau (inventor); Curver Luxembourg Sarl (assignee)

Curver Luxembourg owns U.S. Patent No. D677,946 (‘946) for “Pattern for a chair.” Part of the claimed design was the Y-shaped ornamental feature. Curver originally filed the design patent application with the title “Furniture (part of -),” while the claim recited “Design for a furniture part.” The Examiner allowed the claim but objected to the title, and suggested the “chair” title to Curver. The Examiner cited 37 C.F.R. §1.153, which reads “the title of the design must designate the particular article” (MPEP 1503). Curver agreed to the Examiner’s amendment and allowed the application.

Defendant Home Expressions’ alleged infringing basket product

Defendant Home Expressions’ alleged infringing basket product

After issuance of the ‘946 patent, Curver filed suit against Home Expressions for patent infringement. Home Expressions had basket products utilizing a similar Y-shaped ornamental feature. Home Expressions filed a motion to dismiss, arguing that their product did not infringe the ‘946 patent because it was directed to baskets, and the ‘946 patent was directed to chairs. The district court applied prosecution history estoppel and granted the motion, and Curver appealed.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges Chen, Hughes, and Stoll, with Judge Chen writing for a unanimous court. Judge Chen noted that §1.153 determines that:

- the design claim is not directed to a design per se, but a design for an identified article, and 2) the scope of the design claim can be defined either by the figures (“as shown”) or by a combination of the figures and the language of the design patent (“as shown and described”). Thus, to obtain a design patent, §1.153(a) requires that the design be tied to a particular article, but this regulation permits claim language, not just illustration alone, to identify the article.

Curver argued that prosecution history estoppel (MPEP 2173.02(III)(B)) was misapplied to limit the scope of the ‘946 patent. Curver argued that it did not surrender the broader “furniture” scope when it agreed to the Examiner’s amendment to “chair,” because the Examiner allowed the claim with the broadened “furniture” language. Judge Chen replied:

While we agree that courts typically look to the figures to define the invention of the design patent, it is inappropriate to ignore the only identification of an article of manufacture just because the article is recited in the design patent’s text, rather than illustrated in its figures.

Judge Chen responded that:

Under this ordinary observer test, Curver does not dispute that the district court correctly dismissed Curver’s claim of infringement, for no “ordinary observer” could be deceived into purchasing Home Expression’s baskets believing they were the same as the patterned chairs claimed in Curver’s patent.

He further stated that the ordinary observer test is the only test to determine anticipation of design patents. The ordinary observer test requires consideration of the design as a whole, and determines whether “the deception that arises is a result of the similarities in the overall design not of similarities in ornamental features in isolation” (MPEP 1504.02).

The obvious takeaway is that design patent applicants should maintain caution when agreeing to title amendments during prosecution. Curver notes, in dicta, that the design should reference the article of manufacture because it is a component of a product, as illustrated by the drawings. Judge Chen carefully cited the Supreme Court case in Samsung v. Apple,2 using Apple’s design patents as an example. Apple argued, and was demonstrated by its drawings, that its multi-components were all part of a complex smartphone product. Curver could not argue, Judge Chen posited, the Y-shaped weave ornamentation was an essential component of its article of manufacture. The Samsung case is instructive for design patent applicants to carefully analyze whether prosecution history estoppel materially limits the design’s scope, when choosing Examiner’s amendments, especially to the title. The downside for this strategy, however, is that the title could lead to abstraction, which would raise immediate subject matter eligibility issues under 35 U.S.C. §101 (design patents are treated no differently than utility patents when applying §101 during prosecution). One possible mechanism, alluded by Judge Chen in Curver, is the alternative use of copyright protection for the ornamental designs, consistent with Star Athletica.3

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2019) (slip op.), aff’g Case No. 2:17-cv-4079-KM-JBC (Paper No. 17) (D.N.J. Jan. 8, 2018). ↩

-

See Samsung Elecs. Co. v. Apple Inc., 580 U.S.___, 137 S. Ct. 429, 433-35 (2016). ↩

-

See Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, 580 U.S.___, 137 S. Ct. 1002, 1012 (2017) (“a feature of the design of a useful article is eligible for copyright if, when identified and imagined apart from the useful article, it would qualify as a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work either on its own or when fixed in some other tangible medium”). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent