Limitations on State Sovereign Immunity on Venue

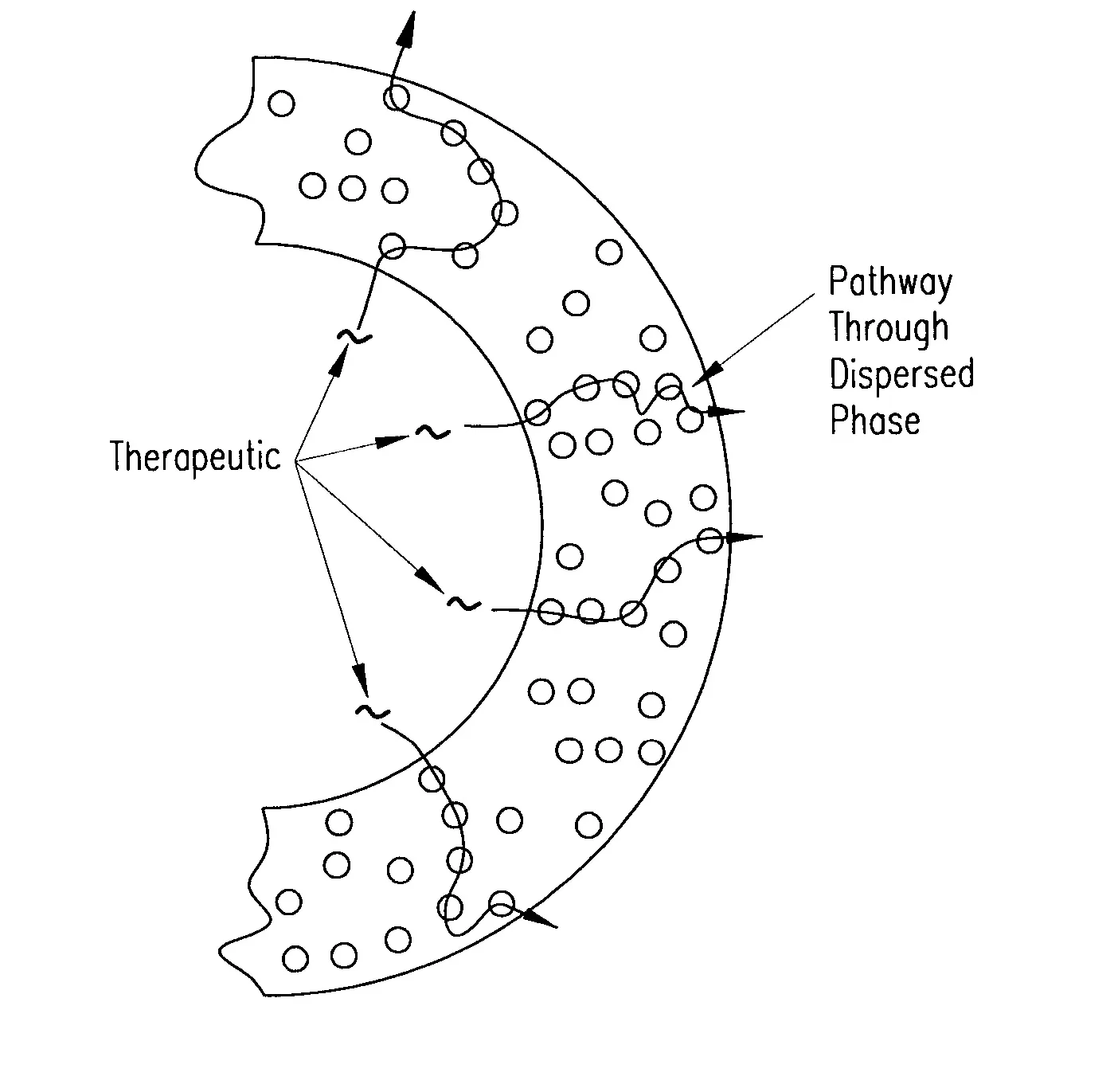

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,033,603, Apr. 25, 2006, to Kevin D. Nelson & Brent B. Crow (inventors); Board of Regents of the Univ. of Texas (assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,033,603, Apr. 25, 2006, to Kevin D. Nelson & Brent B. Crow (inventors); Board of Regents of the Univ. of Texas (assignee)

The issue of sovereign immunity has been raised several times in recent memory at the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, including St. Regis Mohawk Tribe v. Mylan Pharms., Inc*.*,1 (discussed on the blog here), and Regents of the Univ. of Minn. v. LSI Corp*.*,2 (discussed here). Board of Regents of the Univ. of Texas Syst. v. Boston Sci. Corp*.*,3 is the third in that penumbra, decided on September 5, 2019. While the issue of sovereign immunity may not be an entirely settled area of Fed Circuit case law, venue should be, based on the recently-decided T.C. Heartland,4 (discussed here), and Cray,5 decision. Nevertheless, this case tested the limits of state sovereign immunity at the juncture of jurisdiction and venue.

The University of Texas (UT) sued BSC for patent infringement of its U.S. Patent Nos. 6,596,296 and 7,033,603, in the Western District of Texas. The district court held that venue was improper under 28 U.S.C. §1400(b), and granted the motion for improper transfer, transferring the case to the District of Delaware. UT appealed.

The Eleventh Amendment, which reads:

The judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by citizens of another state, or by citizens or subjects of any foreign state.

UT had argued that under principles of state sovereign immunity, through the Eleventh Amendment, that patent venue was proper in the Western District of Texas because as an arm of the Texas sovereign, UT did not have to pursue claims outside of Texas, nor did it have to respond to counterclaims outside of Texas, pursuant to the Eleventh Amendment. BSC had argued that it had no physical presence in the Western District of Texas, with the exception of several employees who worked from home in that district, which, on its face, would be contrary to the T.C. Heartland/Cray principles.

The Fed Circuit panel was comprised of Chief Judge Prost, and Judges Reyna and Stoll, with Judge Stoll writing for the unanimous court. UT had re-argued its position that the Eleventh Amendment did not compel it to be subject to the patent venue statute under §1400(b). UT argued, as a sovereign, it could assert its patent rights in whatever forum it chooses, and further the Delaware court lacks jurisdiction over UT since it did not consent to the suit there. Judge Stoll first noted that the Eleventh Amendment applies to suits against a state, not suits by a state.6 Applying that Fed Circuit precedent in Eli Lilly, and further back to the U.S. Supreme Court old case law, she noted:

The right of the state to assert, as plaintiff, any interest it may have in a subject, which forms the matter of controversy between individuals, in one of the courts of the United States, is not affected by the Eleventh amendment; nor can it be so constructed as to oust the court of its jurisdiction, should such claim be suggested. The amendment simply provides, that no suit shall be commenced or prosecuted against the state. The state cannot be made a defendant to a suit brought by an individual; but it remains the duty of the courts of the United States to decide all cases brought before them by citizens of one state against citizens of a different state, where a state is not necessarily a defendant.7

She further elucidated that:

We thus hold that sovereign immunity cannot be asserted to challenge a venue transfer in a patent infringement case where a State acts solely as a plaintiff.

In other words, where the State acts to assert its rights in a court, the Eleventh Amendment immunity cannot be used to circumvent the regular venue statute under §1400(b).

UT persisted, arguing that the “state can dictate where it litigates its property rights.” Judge Stoll rejected this argument, stating:

[The Supreme Court cases in] Ayers. Pennhurst and Feeney are all distinguishable as none involved the assertion of sovereign immunity by a State as a plaintiff. We are aware of no cases in which the Supreme Court has applied the Eleventh Amendment to suits in which a State is solely a plaintiff.

UT further argued the Original Jurisdiction Clause of Art. III, §2, Cl. 2, which grants the Supreme Court original jurisdiction over cases where a State is a party, and citing a line of Supreme Court cases, claimed a State has the right to control the forum where it chooses to sue a citizen of another state. In making this argument, UT claims it “(a) has a Constitution-rooted right to avoid out-of-state venues, but also that (b) it has an affirmative right to sue in a federal district court that Congress deemed unavailable.” Judge Stoll scoffed at this argument. She wrote:

The original jurisdiction cases cited by UT do not support the proposition that a State can bring suit in any forum as long as personal jurisdiction requirements are met. These cases are further inapposite because UT never even sought to invoke original jurisdiction. It brought this suit “pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§1331 and 1338(a).” Whether UT could have instituted this suit as an original proceeding in the Supreme Court is irrelevant because UT brought suit in a federal district court under federal question jurisdiction.

UT finally argued that it had inherent powers as a sovereign to pursue the forum of choice. However, Judge Stoll rejected this argument, reining in state sovereign immunity by stating:

We acknowledge that States are sovereign entities that entered the Union with particular sovereign rights intact. We are not convinced, however, that the inherent powers of Texas as a sovereign allow UT to disregard rules governing venue in patent infringement suits once it chose to file such aa suit in federal court … . When a State voluntarily appears in federal court, as UT has done here, it “voluntarily invokes the federal court’s jurisdiction.”

The panel affirmed the transfer of venue judgment of the district court.

Footnotes

-

896 F.3d 1322 (Fed. Cir. 2018). ↩

-

926 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2019). ↩

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2019) (slip op.), aff’g Case No. 1:17-cv-1103 (Paper No. 27) (W.D. Tex. Mar. 12, 2018). ↩

-

T.C. Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC, 581 U.S.___, 137 S. Ct. 1514 (2017). ↩

-

In re Cray Inc., 871 F.3d 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2017). ↩

-

Quoting Regents of Univ. of Calif. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 119 F.3d 1559, 1564 (Fed. Cir. 1997). ↩

-

See Eli Lilly, 119 F.3d at 1564; see also United States v. Peters, 9 U.S. (5 Cranch) 115 (1809). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent