Fed Circuit Watch: Fed Circuit Declines to Expand Design Patent Law

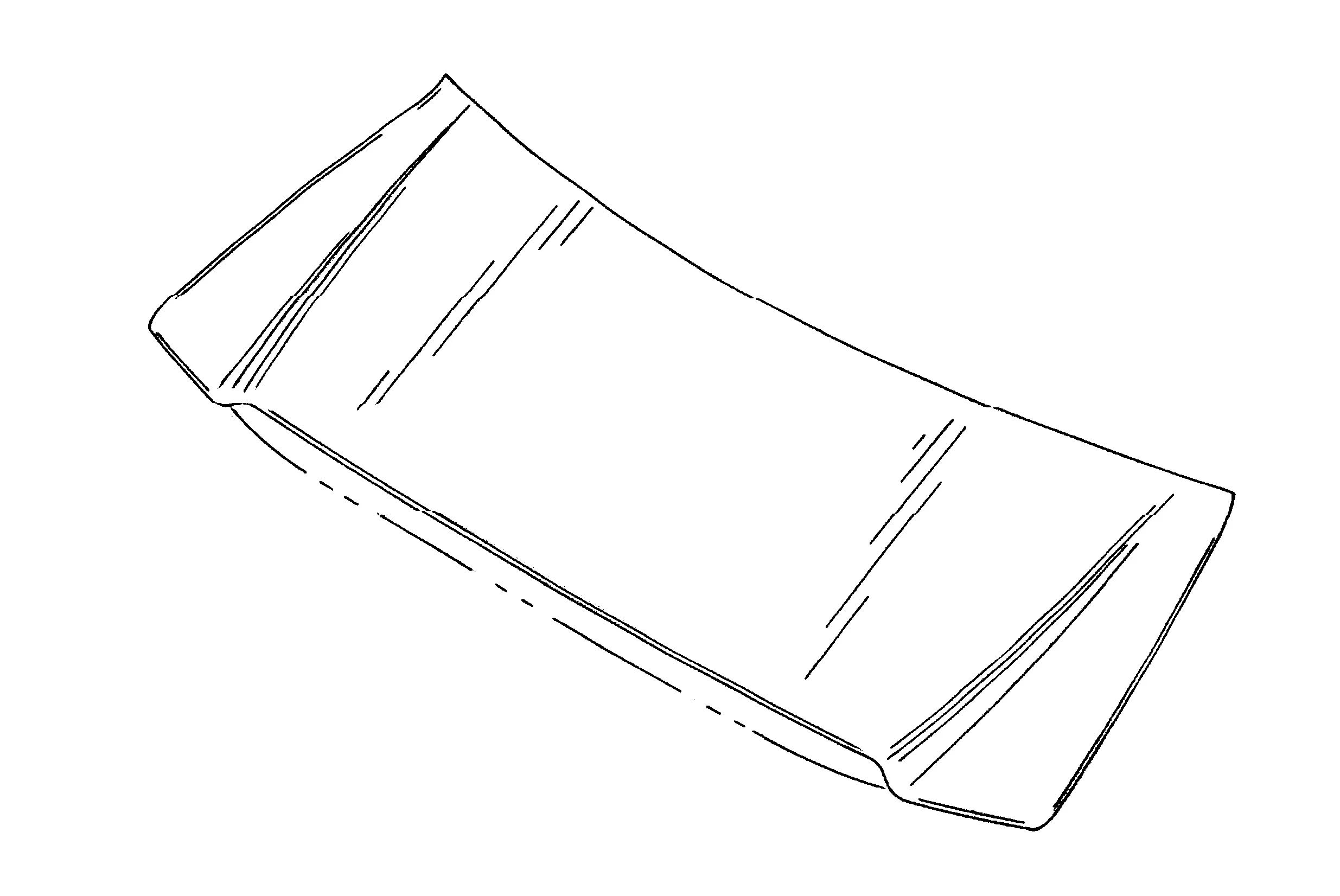

Source: U.S. Patent D489,299 S, May 4, 2004, Craig Metros, Patrick J. Schiavone, & Tyler J. Blake (inventors); Ford Global Technologies, LLC (assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent D489,299 S, May 4, 2004, Craig Metros, Patrick J. Schiavone, & Tyler J. Blake (inventors); Ford Global Technologies, LLC (assignee)

On July 23, 2019, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit publicly released an intriguing design patent ruling involving design patents covering Ford’s F-150 truck. In Automotive Body Parts Assn. v. Ford Global Techs., LLC,1 the Fed Circuit declined to expand trademark law’s functionality doctrine to design patent law, and also declined to create design patent-specific principles of the exhaustion and right to repair doctrines.

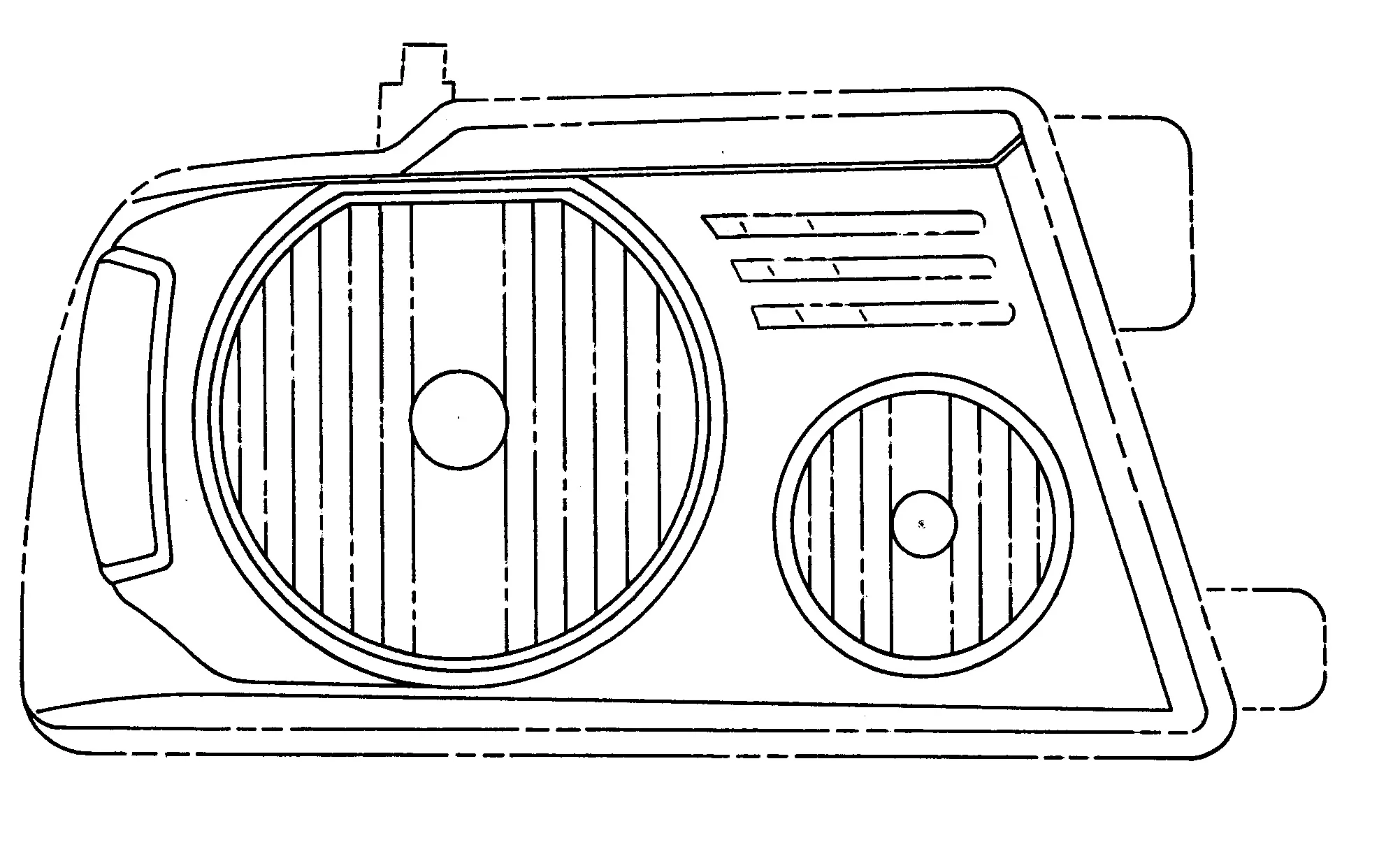

Ford owns U.S. Patent No. D489,299 (‘299) entitled “Exterior of vehicle hood,” and D501,685 (‘685), entitled “Vehicle head lamp,” both of which encompass aesthetic elements of the F-150 truck design.

Source: U.S. Patent D501,685 S, Feb. 8, 2005, Craig Metros, Jeffery M. Nowak, Patrick J. Schiavone, & Tyler J. Blake (inventors); Ford Global Technologies, LLC (assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent D501,685 S, Feb. 8, 2005, Craig Metros, Jeffery M. Nowak, Patrick J. Schiavone, & Tyler J. Blake (inventors); Ford Global Technologies, LLC (assignee)

Ford initially sued the ABPA, an association of auto body part manufacturers and distributors, at the ITC for infringement of the ‘299 and ‘685 patents. The ITC found in favor of Ford as to invalidity and enforceability of these patents. Undeterred, ABPA sued in district court for a declaratory judgment of invalidity and unenforceability. The district court also found in favor of Ford, and granted sua sponte summary judgment in Ford’s favor. ABPA appealed.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges Hughes, Schall, and Stoll, with Judge Stoll writing for a unanimous court. She noted, importantly, that design patents under 35 U.S.C. §171(a) operate differently than utility patents in that a design patent claims ornamental features of the product, and not the functional features like utility patents. While there are some utilitarian aspects of the invention which are indispensable to the analysis, the focus is on the invention’s aesthetic aspects.

However, as to invalidity, rather than argue the ‘299 and ‘685 patents were purely functional, ABPA argued instead that the hood and headlamp designs were aesthetic as functioning to the F-150 truck design. Judge Stoll noted that ABPA was arguing an expansion of trademark law’s aesthetic functionality doctrine to design patent law, for which she pointedly refused to do. The functionality doctrine prevents one party from obtaining exclusivity over trade dress or functional aspects of a product or packaging. She wrote:

[ABPA] asks us to borrow the principle of “aesthetic functionality” from trademark law … ABPA acknowledges that no court has applied “aesthetic functionality” to design patents, but it asks us to become the first. We decline.

She further opined:

Trademarks ensure that a particular producer reaps the rewards – and bears the risks – of its products’ quality and desirability. It follows that a company not indefinitely inhibit competition by trademarking features, whether utilitarian or aesthetic, “that either are not associated with a particular producer or that have value to consumers that is independent of identification.” In contrast, design patents expressly grant to their owners exclusive rights to a particular aesthetic for a limited period of time. The considerations that drive the aesthetic functionality doctrine of trademark law simply do not apply to design patents.

As to the unenforceability of the ‘299 and ‘685 patents, ABPA argued two doctrines common in utility patents – exhaustion and right of repair. ABPA argued that when a consumer purchased an F-150 truck, the exhaustion doctrine would dictate that the first sale terminates any design patent rights may have in Ford’s designs of the F-150 replacement parts. ABPA essentially argued a re-defined exhaustion doctrine specific to design patents. Judge Stoll would have none of this argument, stating:

[E]xhaustion attaches only to items sold by, or with the authorization of, the patentee … But we apply the same rules to design and utility patents whenever possible. Accordingly, we have held that principles of prosecution history estoppel, inventorship, anticipation, and obviousness apply to both design patents and utility patents … We see no persuasive reason to depart from this standard for the exhaustion doctrine.

ABPA then tried to argue that the right of repair doctrine licensed consumers to repair the F-150 trucks with replacement parts embodying Ford’s designs protected by the ‘299 and ‘685 patents, but that did not necessarily require using Ford replacement parts. Judge Stoll remained unpersuaded by this line of argument.

The right of use transferred to a purchaser by an authorized sale “includes the right to repair the patented article. The right of repair does not, however, permit a complete reconstruction of a patented device or component … [T]hough a sale of the F-150 truck permits the purchaser to repair the designs as applied to the specific hood and headlamps sold on the truck, the purchaser may not create new hoods and headlamps using Ford’s designs.

The panel affirmed judgment of the district court.

This decision was ultimately the correct one decided by the Fed Circuit. By declining to extend trademark law’s functionality doctrine and refusing to carve out separate doctrines of exhaustion and right to repair, the Fed Circuit bolstered the design patent law and ensured the patent law applies equally to design patents as it does to utility patents.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2019) (slip op.), aff’g 293 F. Supp. 3d 690 (E.D. Mich. 2018). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent