Fed Circuit Watch: EV Battery Claims Found Patent-Ineligible

What had opened with a promise of clarity for patent subject matter eligibility under 35 U.S.C. §101 took a detour with the ChargePoint, Inc. v. SemaConnect, Inc.,1 decision issued on March 28 2019, by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

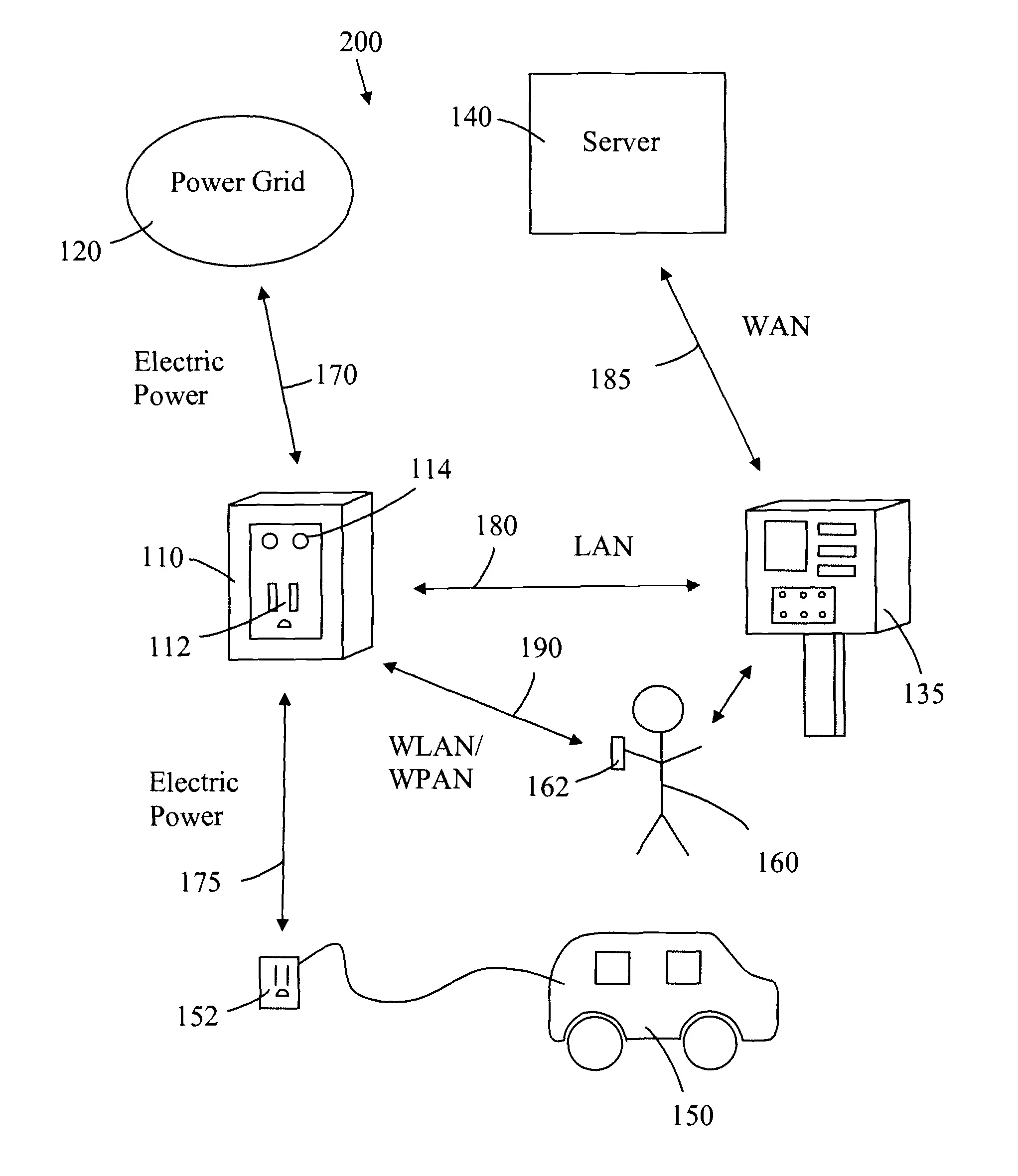

Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,137,715, Mar. 20, 2012, to Richard Lowenthal, Dave Baxter, Harjinder Bhade, & Praveen Mandal (inventors); Coulomb Technologies, Inc. (assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,137,715, Mar. 20, 2012, to Richard Lowenthal, Dave Baxter, Harjinder Bhade, & Praveen Mandal (inventors); Coulomb Technologies, Inc. (assignee)

Four patents were at-issue, all owned by ChargePoint: U.S. Patent Nos. 8,138,715 (‘715), 8,432,131 (‘131), 8,450,967 (‘967), and 7,956,570 (‘570). The patents, sharing the same specification, are directed to apparatuses and methods of network-connected e-vehicle charging stations. The inventions created improvements in the way charging stations addressed inherent e-charging by utilizing a network, providing central management for the charging stations as well as providing data to drivers, making the entire charging system interact more “intelligently” with the electric grid. ChargePoint asserted the four patents against SemaConnect in a patent infringement suit. The district court granted SemaConnect’s Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss based on §101 ineligibility, which ChargePoint appealed.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Chief Judge Prost, and Judges Reyna and Taranto, with Chief Judge Prost writing for a unanimous court. She found ChargePoint’s contention that its claimed inventive concept was defective:

[T]he alleged “inventive concept” that solves problems identified in the field is that the charging stations are network-controlled. But network control is the abstract idea itself, and “a claimed invention’s use of the ineligible concept to which it is directed cannot supply the inventive concept that renders the invention ‘significantly more’ than the ineligible concept.”

Claim 1 of the ‘715 patent is an apparatus claim reciting:

- An apparatus, comprising:

a control device to turn electric supply on and off to enable and disable charge transfer for electric vehicles;

a transceiver to communicate requests for charge transfer with a remote server and receive communications from the remote server via a data control unit that is connected to the remote server through a wide area network; and

a controller, coupled with the control device and the transceiver, to cause the control device to turn the electric supply on based on communication from the remote server.

She noted that “it is clear from the language of claim 1 that the claim involves an abstract idea, namely, the abstract idea of communicating requests to a remote server and receiving communications from the server.”

Claim 1 of the ‘131 patent is an apparatus claim reciting:

- An apparatus, comprising:

a control device to control application of charge transfer for an electric vehicle;

a transceiver to communicate with a remote server via a data control unit that is connected to the remote server through a wide area network and receive communications from the remote server, wherein the received communications include communications as part of a demand response system; and

a controller, coupled with the control device and the transceiver, to cause the control device to modify the application of charge transfer based on the communications received as part of the demand response system.

Chief Judge Prost also opined that the ‘131 patent claims are directed to a “demand response,” which is essentially the market principle of supply and demand, an otherwise abstract idea.

Claim 1 of the ‘967 patent is a method claim reciting:

- A method in a server of a network-controlled charging system for electric vehicles, the method comprising:

receiving a request for charge transfer for an electric vehicle at a network-controlled charge transfer device;

determining whether to enable charge transfer;

responsive to determining to enable charge transfer, transmitting a communication for the network-controlled charge transfer device that indicates to the network-controlled charge transfer device to enable charge transfer; and

transmitting a communication for the network-controlled charge transfer device to modify application of charge transfer as part of a demand response system.

Chief Judge Prost summarily rejected the eligibility of the ‘967 patent because its specification lacked “any technical details regarding how to modify electricity flow, and the fact that any modifications are made in response to a demand response policy merely adds one abstract concept to another.”

Claim 31 of the ‘570 patent is an apparatus claim reciting:

- A network-controlled charge transfer system for electric vehicles comprising:

a server;

a data control unit connected to a wide area network for access to said server; and

a charge transfer device, remote from said server and said data control unit, comprising:

an electrical receptacle configured to receive an electrical connector for recharging an electric vehicle;

an electric power line connecting said receptacle to a local power grid;

a control device on said electric power line, for switching said receptacle on and off;

a current measuring device on said electric power line, for measuring current flowing through said receptacle;

a controller configured to operate said control device and to monitor the output from said current measuring device;

a local area network transceiver connected to said controller, said local area network transceiver being configured to connect said controller to said data control unit; and

a communication device connected to said controller, said communication device being configured to connect said controller to a mobile wireless communication device, for communication between the operator of said electric vehicle and said controller.

She noted that the only improvement the ‘570 claims were directed to is the use of network communications to interact with the system, which is only directed to an abstract idea.

Chief Judge Prost concluded with:

[T]he only possible inventive concept in the eight asserted claims is the abstract idea itself. ChargePoint, of course, disagrees with this characterization, arguing that its patents claim “charging stations enabled to use networks, not the network connectivity itself.” But the specification gives no indication that the patented invention involved how to add network connectivity to these charging stations in an unconventional way. From the claims and the specification, it is clear that the network communication is the only possible inventive concept. Because this is the abstract idea itself, this cannot supply the inventive concept at step two. The claims are therefore ineligible.

This case’s opinion does not juxtapose vis-à-vis the latest Revised Subject Matter Eligibility Guidelines issued by the USPTO this past January. According to the Revised Guidelines, a patent application claim can be grouped as a class of abstract idea (e.g., mathematical concept, organizing human activity, or mental process), but that claim is not an abstract idea itself if it is directed to a practical application of the judicial exception (i.e., abstract idea). Here, the claims-at-issue all appear directed to that practical application – that is, an electric charging station (i.e., the apparatus claims) and process for charging (i.e., the method claims), all through a network environment would appear to be practical applications of the abstract idea of networking. What had been a promising start to 2019 in terms of providing more clarity to the subject matter eligibility debate has now been become a cluttered mess (again) with this latest ChargePoint decision.

As more precedential §101 opinions are released this year, we will update this blog with additional insight. Perhaps this trend is still early, but midway through the year, the argument for overcoming §101 rejections has become rather bleak.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2019) (slip op.), affirming Case No. 17-3717, 2018 WL 1471685 (D. Md. Mar. 23, 2018). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent