Fed Circuit Watch: Party Lacks Both Sovereign Immunity and Patent-Eligible Treatment Claims

In one of the more fascinating legal analyses presented in recent memory, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed down Univ. of Florida Res. Foundation, Inc. v. General Electric Co.,1 on February 26, 2019. The issues presented were state assertion of sovereign immunity in federal court, and method and system of treatment claims as patent-eligible under 35 U.S.C. §101. On both issues, the Fed Circuit affirmed the district court decision, namely, finding no sovereign immunity under the 11th Amendment and the claims invalid under §101.

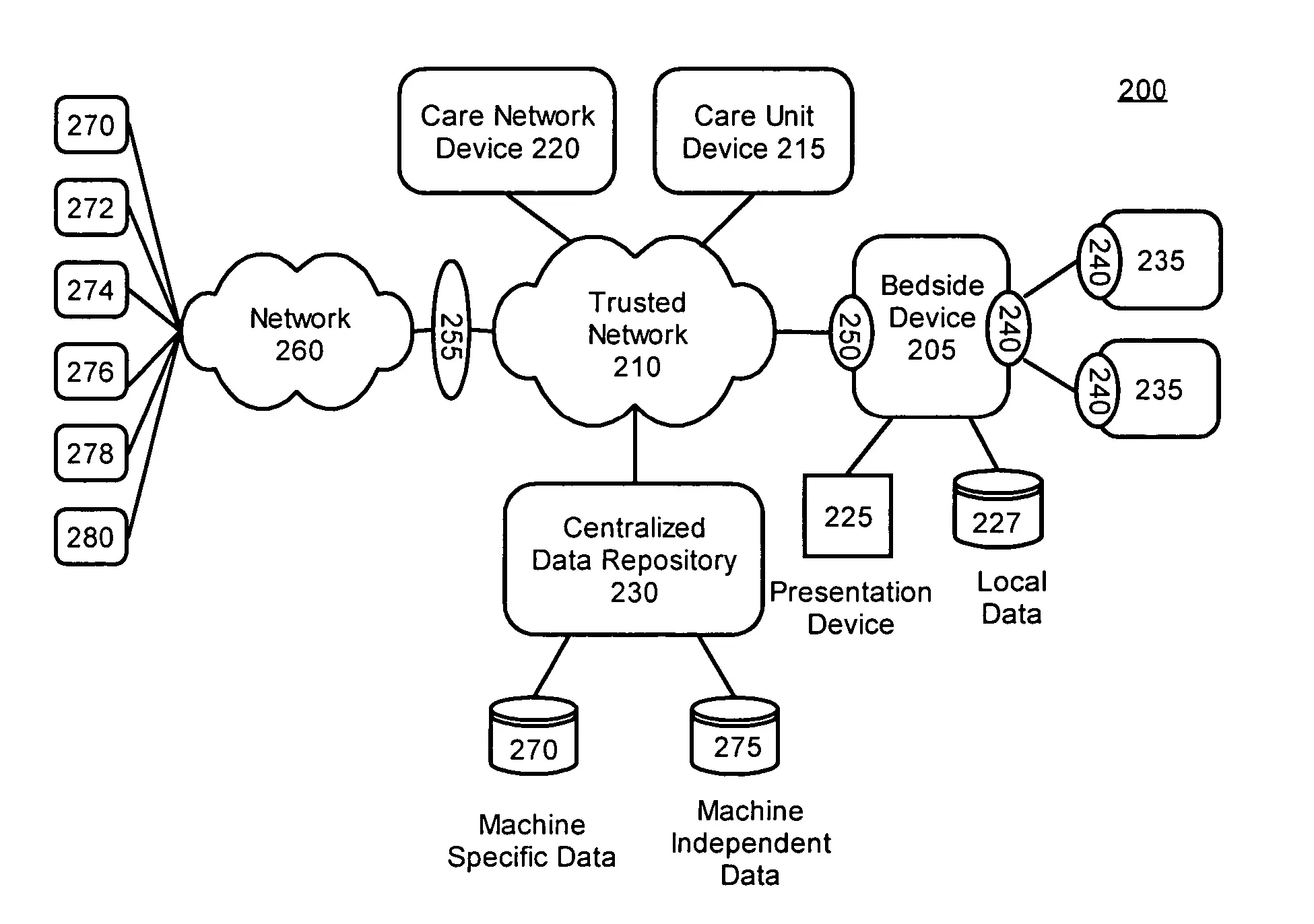

The UFRF owns U.S. Patent No. 7,062,251 (‘251), entitled “Managing critical cate physiologic data using data synthesis technology (DST),” and directed to methods and systems of integrative physiologic treatment data from a bedside GUI. Claim 1 was deemed representative:

A method of integrating physiologic treatment data comprising the steps of:

receiving physiologic treatment data from at least two bedside machines;

converting said physiologic treatment data from a machine specific format into a machine independent format within a computing device remotely located from said bedside machines;

performing at least one programmatic action involving said machine-independent data; and

presenting results from said programmatic actions upon a bedside graphical user interface.

(Emphasis added.)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,062,051, Jun. 13, 2006, to Kevin R. Birkett, Tony C. Carnes, Samuel W. Coons, III, and Willa H. Drummond (inventors); University of Florida Research Foundation, Inc. (assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,062,051, Jun. 13, 2006, to Kevin R. Birkett, Tony C. Carnes, Samuel W. Coons, III, and Willa H. Drummond (inventors); University of Florida Research Foundation, Inc. (assignee)

UFRF filed a suit against GE alleging patent infringement of the ‘251 patent. GE responded to the infringement by arguing the ‘251 was invalid for claiming patent-ineligible subject matter under §101. UFRF further asserted against the §101 defense that, as an extension of a state sovereign (i.e., a public university), it was immune under the state sovereign immunity clause of the 11th Amendment from the patent-ineligibility claim under §101. Waiver of state sovereign immunity occurs when the state consents to federal court jurisdiction by voluntarily appearing before the federal courts, either by way of filing, or defending against, a federal court-filed complaint.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Senior Judge Prost, and Judges Moore and Wallach, with Judge Moore writing for a unanimous panel. The panel first dealt with the sovereign immunity claim as a procedural mechanism, that is, the gateway subject matter jurisdiction for the federal courts, before proceeding to the substantive §101 eligibility issue. The procedural question was whether a §101 invalidity challenge is a defense to patent infringement. Judge Moore perfunctorily announced: “We hold that it is.”

Although 35 U.S.C. §282(b) allows conditions of patentability can act as a valid defense to a patent infringement claim, Judge Moore posited that a §101 eligibility challenge would still be a valid defense to an infringement claim, regardless of §282(b).

We and the Supreme Court have long treated §101 eligibility as a “condition[] of patentability” alongside §§102 and 103 … . We see no reason to depart from this practice now.

She continued:

[W]e hold that a §101 eligibility challenge is a defense to a claim of infringement. By bringing its claim of infringement, UFRF waived its sovereign immunity “not only [as] to the cause of action but also [as] to any relevant defenses … . Because GE’s §101 eligibility challenge is a defense to UFRF’s claim, UFRF has waived sovereign immunity as to GE’s §101 eligibility challenge.

Judge Moore continued to the substantive §101 eligibility analysis. The ‘251 patent teaches automating traditional “pen and paper methodologies,” by receiving and transmitting data via a bedside device. Judge Moore observed:

On its face, the ‘251 patent seeks to automate “pen and paper methodologies” to conserve human resources and minimize errors. This is the quintessential “do it on a computer” patent: it acknowledges that data from bedside machines was previously collected, analyzed, manipulated, and displayed manually, and it simply proposes doing so with a computer. We have held such claims are directed to abstract ideas.2

She noted that the ‘251 specification identifies no specific improvements to the way a computer operates, as required by the Enfish rule.3 The claimed “receiving physiologic treatment data from two bedside machines” was already used in the prior art. Further, the claimed “programmatic action involving said machine-independent data” could be performed through any other type of computer.

Further, she noted that the ‘251 patent only explains the drivers in terms of their functional aspects: “facilitating data exchanges,” “converting received data streams,” “translating data streams,” and “interpreting data streams.” À la Enfish, these mere functional aspects of converting certain computer technology is not a specific improvement in how a computer operates. Therefore, it would fail the §101, and the ‘251 patent would claim patent-ineligible subject matter.

As a result, the Fed Circuit affirmed the district court finding of invalidity and motion to dismiss.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2019) (slip op.), affirming Case No. 1:17cv171-MW/GRJ (Nov. 16, 2017) (granting Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss (2017.11)). ↩

-

See e.g., Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Capital One Fin. Corp., 850 F.3d 1332, 1340 (Fed. Cir. 2017); Elec. Power Grp. LLC v. Alstom S.A., 830 F.3d 1350, 1353-54 (Fed. Cir. 2016). ↩

-

See Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., [822 F.3d 1327](https://www.leagle.com/decision/infco20160512137 enfish), 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (“Rather, they are directed to a specific improvement to the way computers operate, embodied in the self-referential table.”). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent