Medical diagnostics patents involving a certain lab testing company named Mayo took a hit when those patents were deemed invalid under 35 U.S.C. §101. No, it’s not that Mayo case,[1] but the one in which the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit recently decided on February 6, 2019, Athena Diagnostics, Inc. v. Mayo Collaborative Servs., LLC,[2] and ended up with a patent being held invalid, again, under §101.

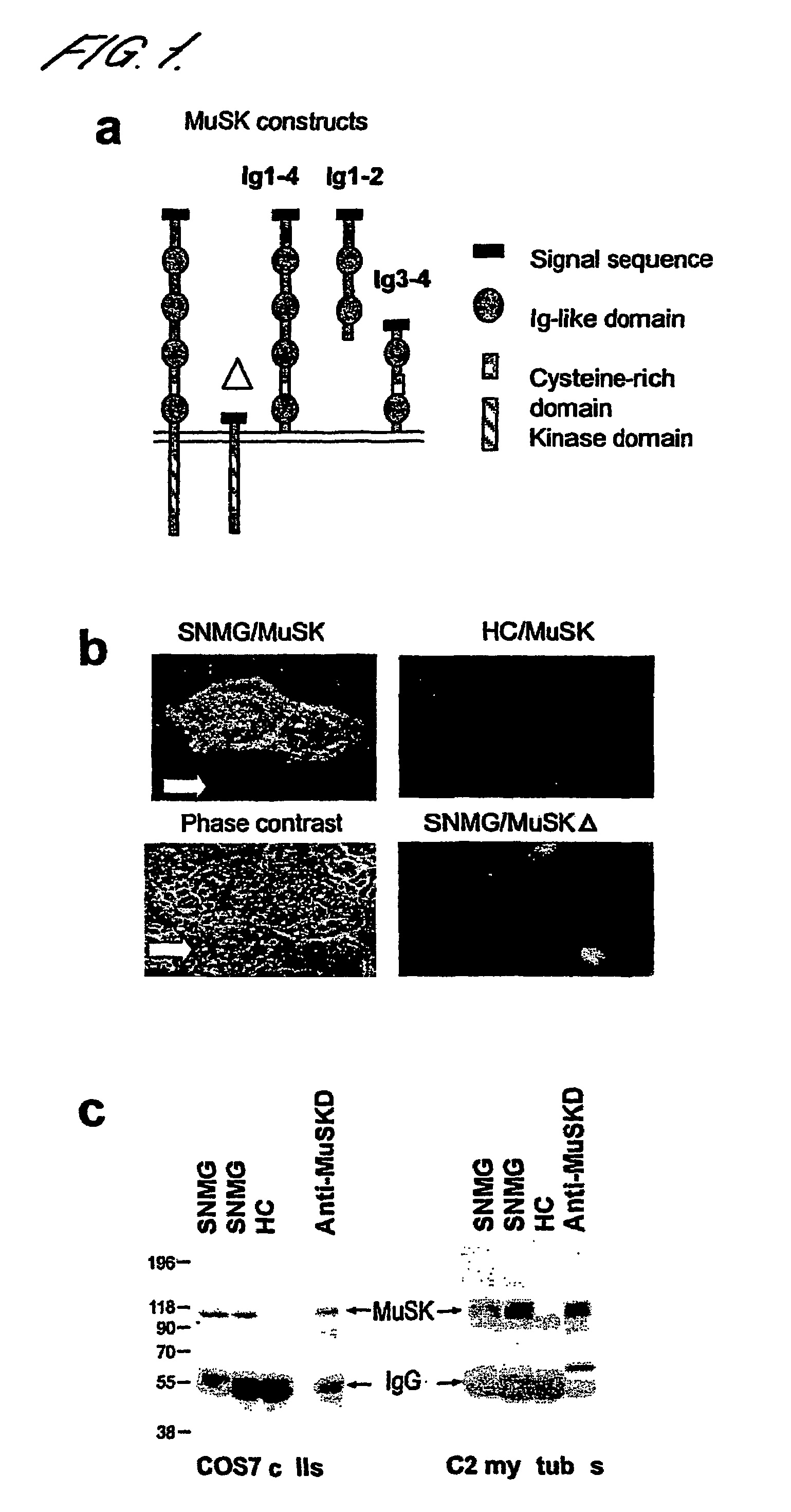

Athena is the exclusive licensee of U.S. Patent No. 7,267,820 (‘820), directed to methods of diagnostic detection of antibodies to the muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) protein for treatment of Myasthenia gravis, a neurological disorder.

Claims 6-9 were at issue. Claims 6-9 are dependent on Claim 1, the only independent claim in the ‘820 patent, which recites:

- A method for diagnosing neurotransmission or developmental disorders related to muscle specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) in a mammal comprising the step of detecting in a bodily fluid of said mammal autoantibodies to an epitope of muscle specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK).

Claims 6-9 recite:

- A method according to claim 3 whereby the intensity of the signal from the anti-human IgG antibody is indicative of the relative amount of the anti-MuSK autoantibody in the bodily fluid when compared to a positive and negative control reading.

- A method according to claim 1, comprising contacting MuSK or an epitope or antigenic determinant thereof having a suitable label thereon, with said bodily fluid, immunoprecipitating any antibody/MuSK complex or antibody/MuSK epitope or antigenic determinant complex from said bodily fluid and monitoring for said label on any of said antibody/MuSK complex or antibody/MuSK epitope or antigen determinant complex, wherein the presence of said label is indicative of said mammal is suffering from said neurotransmission or developmental disorder related to muscle specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK).

- A method according to claim 7 wherein said label is a radioactive label.

- A method according to claim 8 wherein said label is 125I.

Athena filed an infringement suit against Mayo for infringement of its ‘820 patent after Mayo developed two competing MuSK diagnostic tests. The district court held the interaction of 125I-labeled MuSK with MuSK autoantibodies in bodily fluid is a natural occurrence, and, therefore, the ‘820 claims invalid under §101. Further, the district court dismissed Athena’s suit for failure to state a claim under Rule 12(b)(6).

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges Newman, Lourie, and Stoll, with Judge Lourie writing for the majority, and Judge Newman writing in dissent. Judge Lourie noted the Mayo test for establishing patent-eligibility under §101. First, the claims must be directed to a law of nature, inter alia. If so, then the second step requires analyzing the claims individually and in combination to determine if they transform the nature of claim into something more than a law of nature.

Athena had argued that the claims were patent-eligible subject matter because they recited a non-preemptive innovative and concrete steps. Mayo countered, echoing the district court’s holding, that the claims were directed to correlative naturally-occurring MuSK autoantibodies, and each of the remaining elements were anticipated or obvious immunoassay techniques already known in the art. Judge Lourie agreed with Mayo:

We consider it important at this point to note the difference between the claims before us here, which recite a natural law and conventional means for detecting it, and applications of natural laws, which are patent-eligible. Claiming a natural cause of an ailment and well-known means of observing it is not eligible for patent because such a claim in effect only encompasses the natural law itself. But claiming a new treatment for an ailment, albeit using a natural law, is not claiming the natural law.

As for step two, Athena argued that the ‘820 claims were an innovative sequence of steps using man-made molecules. However, Judge Lourie disagreed:

[T]o supply an inventive concept the sequence of claims steps must do more than adapt a conventional assay to a newly discovered natural law; it must represent an inventive application beyond the discovery of the natural law itself. Because claims 7-9 fail to recite such an application, they do not provide an inventive concept.

The majority also criticized Judge Newman’s dissent:

The dissent states much that one can agree with from the standpoint of policy, and history, including that “the public interest is poorly served by adding disincentive to the development of new diagnostic methods.” We would add further that, in our view, providing patent protection to novel and non-obvious diagnostic methods would promote the progress of science and useful arts. But, whether or not we as individual judges might agree or not that these claims only recite a natural law, . . . the Supreme Court has effectively told us in Mayo that correlations between the presence of a biological material and a disease are laws of nature, and “[p]urely ‘conventional or obvious’ ‘[pre]-solution activity’ is normally not sufficient to transform an unpatentable law of nature into a patent-eligible application of such a law,” . . . . Our precedent leaves no room for a different outcome here.

Judge Newman, in retort, wrote:

The ‘820 inventors did not patent their scientific discovery of MuSK autoantibodies. Rather, they applied this discovery to create a new method of diagnosis, for a previously undiagnosed neurological condition . . . . The reaction between the antibody and the MuSK protein was not previously known, nor was it known to form a labeled MuSK or its epitope, nor to form the antibody/MuSK complex, immunoprecipitate the complex, and monitor for radioactivity, thereby diagnosing these previously undiagnosable neuro transmission disorders.

It should be noted that Judge Newman received a Ph.D. in chemistry from Yale University, and is perhaps the foremost chemical arts jurist on the Fed Circuit bench. Judge Newman noted that “Section 101 describes patent-eligible subject matter in broad and general terms,” and “does not exclude new methods of diagnosis of human ailments.” She does make a compelling argument justifying validity of the ‘820 diagnostic claims, but alas, was in the minority of this particular panel.

To sum, the Fed Circuit affirmed the district court judgment that the ‘820 patent was invalid under §101. Given the still unsettled nature of §101 jurisprudence, it should be almost assumed that Athena will seek a petition for rehearing en banc and/or a further petition for writ of certiorari before the U.S. Supreme Court.

[1] See Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012).

[2] ___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2019) (slip op.), aff’g 275 F. Supp. 3d 306 (D. Mass. 2017).