Fed Circuit Watch: Primer and Diagnostic Method Claims Not Patent-Eligible

This is the second §101 case decided by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on October 9, 2018, Roche Molecular Systs., Inc. v. Cepheid.1 This case is not so remarkable because it held patent claims as ineligible subject matter, but because there appears to be disjointed appellate §101 analysis applied between this case and the second case decided on that day by the same court (although with a mostly different panel), Data Engine Techs. LLC v. Google LLC. The facts are as follows.

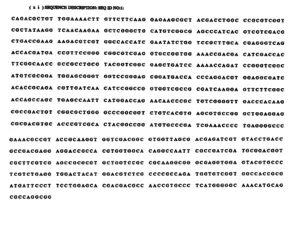

Roche Molecular Systems owns U.S. Patent No. 5,643,723 (‘723), directed to methods for detection of the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis or MTB). There are method claims for detection of M. tuberculosis, through a diagnostic test which identifies whether a biological sample contains M. tuberculosis, and if so, predicts whether the M. tuberculosis strain is resistant to the treatment drug rifampin. The composition claims are directed to the primer having 14-50 nucleotides that hybridize to the M. tuberculosis gene (rpoB). Cepheid makes a competing product that detects M. tuberculosis gene. Roche filed a patent infringement suit against Cepheid alleging infringement of the ‘723 patent. Cepheid filed a motion for summary judgment asserting the ‘723 patent was patent-ineligible under 35 U.S.C. §101. The district court granted the motion, finding that the genetic sequences of the primer claims were identical to those found in nature. The diagnostic claims were also found invalid as ineligible subject matter as natural phenomena because the mere use of newly developed nonpatentable primers to bind the naturally occurring signature nucleotides, and used in a well-known, routine PCR process did not transform the claims into patent-eligible subject matter. Roche appealed.

Source: U.S. Patent No. 5,643,723, Jul. 1, 1997, to David H. Persing, John J. Hunt, Karen K.Y. Young, Teresa A. Felmlee, Glenn D. Roberts, A. Christian Whelan (inventors); Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. & Mayo Foundation For Medical Education & Research (assignees)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 5,643,723, Jul. 1, 1997, to David H. Persing, John J. Hunt, Karen K.Y. Young, Teresa A. Felmlee, Glenn D. Roberts, A. Christian Whelan (inventors); Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. & Mayo Foundation For Medical Education & Research (assignees)

Method and composition of matter (primer)2 claims were at issue. Claim 1, the method claim, recites:

- A method for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a biological sample suspected of containing M. tuberculosis comprising:

(a) subjecting DNA from the biological sample to polymerase chain reaction [PCR] using a plurality of primers under reaction conditions sufficient to simplify a portion of a M. tuberculosis rpoB [gene] to produce an amplification product, wherein the plurality of primers comprises at least one primer that hybridizes under hybridizing conditions to the amplified portion of the [gene] at a site comprising at least one position-specific M. tuberculosis signature nucleotide selected, with reference to FIG. 3 (SEQ ID NO: 1), from the group consisting

a G at nucleotide position 2312,

a T at nucleotide position 2313,

an A at nucleotide position 2373,

a G at nucleotide position 2374,

an A at nucleotide position 2378,

a G at nucleotide position 2408,

a T at nucleotide position 2409,

an A at nucleotide position 2426,

a G at nucleotide position 2441,

an A at nucleotide position 2456,

and a T at nucleotide position 2465; and

(b) detecting the presence or absence of an amplification product, wherein the presence of an amplification product is indicative of the presence of M. tuberculosis in the biological sample and wherein the absence of the amplification product is indicative of the absence of M. tuberculosis in the biological sample.

The composition (primer) claim 17 recites:

- A primer having 14–50 nucleotides that hybridizes under hybridizing conditions to an M. tuberculosis rpoB [gene] at a site comprising at least one position-specific M. tuberculosis signature nucleotide selected, with reference to FIG. 3 (SEQ ID NO: 1), from the group consisting of [the same 11 nucleotides at the positions disclosed in claim 1].

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges O’Malley, Reyna, and Hughes, with Judge Reyna writing for the court. Under the Alice/Mayo framework, a claim is first analyzed to determine if it is directed to patent-ineligible concepts, including laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas. If so, then the elements of the claim, taken as a whole, are analyzed to determine whether the claim contains some “inventive concept” that transforms the claim into patent-eligible subject matter.3

As to the primer claims, Roche had argued that its synthetic primers were different from naturally occurring DNA. Its primers have a 3’ end and a 3’-hydroxyl group, something which naturally occurring M. tuberculosis DNA does not have. However, Judge Reyna disagreed, relying on the In re BRCA1 case as precedent.

BRCA1 forecloses Roche’s arguments. There this court examined the subject matter eligibility of similar primer claims and held that those primers “are not distinguishable from the isolated DNA found patent-ineligible in Myriad” and thus are not patent-eligible.4

He further elucidated from BRCA1 that:

A DNA structure with a function similar to that found in nature can only be patent eligible as a composition of matter if it has a unique structure, different from anything found in nature. Primers do not have such a different structure and are patent ineligible.5

Judge Reyna additionally noted that nothing in the ‘723’s specification is suggestive that the inventors introduced mutations in the primers to make the primer sequences different from those found in nature. Further, he noted that the eleven position-specific signature nucleotides on the rpoB gene which are hybridized by the primers are naturally occurring phenomena. Therefore, the primer claims were deemed patent-ineligible subject matter under §101.

Moving to the method claims, Judge Reyna stated:

Claim 1 establishes that the method claims are directed to a relationship between the eleven naturally occurring position-specific signature nucleotides and the presence of [M. tuberculosis] in a sample. The method claims assert that if an investigator detects a signature nucleotide from a sample, she knows the sample contains [M. tuberculosis]. This relationship between the signature nucleotides and [M. tuberculosis] is a phenomenon that exists in nature apart from any human action, meaning the method claims are directed to a natural phenomenon, which itself is ineligible for patenting.

The written description supports the conclusion that the method claims of the ‘723 patent are directed to a patent-ineligible natural phenomenon.

This invention involves a comparative analysis of the rpoB sequences in MTB [M. tuberculosis], other mycobacteria and related … bacteria … demonstrating the heretofore undiscovered presence of a set of MTB-specific position-specific “signature nucleotides” that permits unequivocal identification of MTB.

…

We hold that the method claims do not contain an inventive concept that transforms the eleven position-specific signature nucleotides of the MTB rpoB gene into patent-eligible subject matter.

Then, Judge Reyna buttressed his opinion with the following:

Roche argues that at the time of the invention, it was “not routine or conventional” to use PCR (or any other genetic test) to detect the presence of MTB in a biological sample” and unprecedented to perform PCR using the type of primer specified in claims 1 through 13 … While it may be true that Roche inventors were the first to use PCR to detect MTB in a biological sample, being the first to discover a previously unknown naturally occurring phenomenon or law of nature alone is not enough to confer patent eligibility.

The panel unanimously found the ‘723 method and primer claims were patent-ineligible under §101, and affirmed judgment.

Judge O’Malley’s concurrence reads more like a dissent. She noted that in BRCA1, the focus was on the procedural elements of that case, whereas in this case, the focus is squarely on patent-specific law. In BRCA1, the BRCA1 movant-appellant, the patentee, had to persuade the Fed Circuit that the district court abused its discretion in denying the motion for preliminary injunction. The district court must make its ruling based on the persuasiveness of movant’s evidence, knowing that it is doing so without an entire record or full evidence as would come out at trial; the court does not determine patent validity at the hearing. Here, Roche, as patentee-appellant, had a full opportunity to present its entire evidentiary basis for validity on its ‘723 patent, and especially on the primer claims. Because there was a lack of a full evidentiary record for the BRCA1 case to determine validity of the primer claims in that case which was not available in this case, Judge O’Malley believed:

[P]erhaps because of the procedural posture in which the issue was developed, the patent owner in BRCA1 did not develop a record demonstrating that primers differ structurally from native DNA based on the presence of a hydroxyl group at a nonnaturally occurring location. Nor did we expressly address this hydroxyl group “argument” in BRCA1 or include language indicating that we had considered, but rejected, any such argument … . The patent owner in BRCA1 also never argued that its claimed primers were structurally distinct from naturally occurring primers.

She observed that primers were not addressed in the Supreme Court’s Myriad decision. She concludes her opinion:

For these reasons, while I agree with the majority that the broad language of our holding in BRCA1 compels the conclusion that the primer claims in this case are ineligible under 35 U.S.C. §101, I believe that holding exceed the confines of the issue raised on appeal and was the result of an underdeveloped record in that case. I believe, accordingly, that we should revisit our conclusion in BRCA1 en banc.

There are a couple of concerns with Roche, and compared with Data Engine, which were decided on the same day with different results. First, Judge Reyna, who was also on the panel in Data Engine, easily conflated the §101 patent-eligibility analysis with a novelty analysis under 35 U.S.C. §102, and even a little nonobviousness analysis under 35 U.S.C. §103. This conflation of patent legal analyses have traditionally been conducted separately. Mixing a §101 analysis with other patentability analyses makes the patent practice much more difficult. Further, this ruling is diametrically opposite to the Data Engine case which was decided on the same day, of which Judge Stoll specifically refused to fluidize patent-eligibility as a §§101-102-103 continuum. This was a concern with earlier-decided §101 cases, and it appears the trend is continuing. Second, Judge O’Malley’s concerns about an erroneously decided BRCA1 case appear real. The unresolved issues of material fact make BRCA1 a difficult precedent for Roche, especially since it was decided just shortly after the Supreme Court ruled in the landmark Myriad Genetics case, making BRCA1 was one of the earliest §101 cases decided by the Fed Circuit when the court was beginning to grapple with patent-eligibility. The larger picture is still clouded, especially after several cases decided earlier in the year seemed to portend more clarity and predictability into the §101 jurisprudence. However, at year’s end that does not seem to be the case.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), aff’g Case No. 14-CV-03228-EDL, 2017 WL 63411568 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 17, 2017). ↩

-

A primer is a shortened, single-strand of DNA or RNA, roughly 18-22 bases, that begins DNA synthesis. DNA polymerases, the enzymes that replicate DNA, can only add new nucleotides to an already-existing strand of DNA. ↩

-

See Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 77-79 (2012); see also Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S. Ct. 2347, 2354 (2014). ↩

-

See In re BRCA1- & BRCA2-Based Hereditary Cancer Test Patent Litig., 774 F.3d 755, 760 (Fed. Cir. 2014); see also Ass’n for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. 576, 591 (2013). ↩

-

BRCA1, supra, at 761. ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent