Fed Circuit Watch: PTAB Messed Up Obviousness Analysis (Again)

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) seems to have bungled an obviousness analysis (again), and was dinged by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in E.I. DuPont de Nemours v. Synvina C.V.,1 decided on September 17, 2018. The case is a good primer on the law of obviousness related to overlapping ranges.

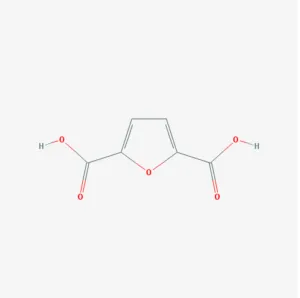

Synvina C.V. owns U.S. Patent No. U.S. Patent No. 8,865,921 (‘921), directed to a method of oxidizing 5-methylfurfural (HMF) or an HMF derivative under specific reaction conditions to form 2,5-furan dicarboxylic acid (FDCA). The issue on appeal revolves around whether the claimed reaction conditions using temperature, pressure, a catalyst, and a solvent would be obvious to one of ordinary skilled in the art (POSITA).

2,5-Furandiocarboxylic acid chemical structure. Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,865,921 B2, to Cesar Muñoz De Diego, Matheus Adrianus Dam, Gerardus Johannes Maria Gruter (inventors), Furanix Technologies B.V. (assignee)

2,5-Furandiocarboxylic acid chemical structure. Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,865,921 B2, to Cesar Muñoz De Diego, Matheus Adrianus Dam, Gerardus Johannes Maria Gruter (inventors), Furanix Technologies B.V. (assignee)

Claim 1 was deemed representative:

- A method for the preparation of 2,5-furan dicarboxylic acid comprising the step of contacting a feed comprising a compound selected from the group consisting of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (“HMF”), an ester of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, 5-methylfurfural, 5-(chloromethyl)furfural, 5-methylfuroic acid, 5-(chloromethyl)furoic acid, 2,5-dimethylfuran and a mixture of two or more of these compounds with an oxygen-containing gas, in the presence of an oxidation catalyst comprising both Co and Mn, and further a source of bromine, at a temperature between 140° C. and 200° C., at an oxygen partial pressure of 1 to 10 bar, wherein a solvent or solvent mixture comprising acetic acid or acetic acid and water mixtures is present.

(Emphasis added.)

The reaction conditions are disclosed in the ‘921 specification, which include the reaction occurring at a temperature “higher than 140° C, preferably from 140° C. and 200° C., and most preferably between 160° C. and 190° C.” Further, the oxygen partial pressure occurs between 1 and 30 bar or more preferably at 1 and 10 bar.

DuPont petitioned for IPR of the ‘921 patent against Furanix B.V. Synvina acquired the ‘921 patent from Furanix during the IPR proceedings. DuPont sought review on two grounds: 1) claims 1-5 were invalid as obvious over International Publication No. WO 01/72732 (‘732), alone and in combination with Inventor’s Certificate RU-448177 (RU ‘177) and U.S. Patent Publication No. 2008/0103318 (‘318), and 2) claims 7-9 invalid as obvious over two published articles, Lewkowski and Oae.2 The first three references disclosed oxidation of HMF to produce FDCA, but under different conditions. The following table outlines the comparisons between the ‘921 patent and the prior art:

| Reference | Temperature | Pressure | Solvent | Catalyst |

| ‘921 patent | Between 140-200°C | 1 – 10 bars | Acetic acid | Co/Mn/Br |

| RU ‘177 | 115-140°C | 2.1 – 10.5 bars | Acetic acid | Co/Mn/Br |

| ‘732 | 50 – 250°C, preferably 50-160°C | 14.5 bars | Acetic acid | Co/Mn/Br, optimally Zr |

| ‘318 | 50-200°C, preferably 100-160°C | 2.17 – 7.24 bars | Water | Pt |

The PTAB instituted review of claims 1-5 and 7-9 based on grounds 1 and 2 only; partial review was not challenged by either party on appeal.3 Although the PTAB considered objective evidence of nonobviousness, this consideration was deemed less probative in supporting a finding of nonobviousness. Although the PTAB found evidence inadequate to support Furanix’s unexpected results (MPEP 716.02) nor solved a long-felt need (MPEP 716.04), it still found the claims nonobvious, and therefore, not invalid. DuPont appealed.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges Lourie, O’Malley, and Chen, with Judge Lourie writing for the court. To start, as Judge Lourie noted, the “legal principle at issue in this case is old.”4 Indeed, it is settled precedent, as well as established USPTO examination guidelines, that claimed ranges that overlap or lie inside the ranges of the prior art create a prima facie case of obviousness (MPEP 2144.05).5 When a prima facie case of obviousness is established, the burden shifts to the patentee to introduce evidence to rebut the prima facie case (MPEP 2145). Rebuttal evidence may include “secondary considerations,” including commercial success, long felt but unsolved needs, failure of others, or unexpected results from improved properties of the claimed invention over the prior art.

Judge Lourie did observe that this was the first time an overlapping range obviousness analysis applies to a case initiated from an IPR. Nevertheless, the same legal principles and precedent still applied, he noted.

“[W]here there is a range disclosed in the prior art, and the claimed invention falls within that range, the burden of production falls upon the patentee to come forward with evidence” of teaching away, unexpected results or criticality, or other pertinent objective indicia indicating that the overlapping range would not have been obvious in light of that prior art.6

The panel agreed with DuPont that the PTAB erred in finding the PO2 and temperature of the oxidation reaction were not result-effective variables (MPEP 2144.05(II)(B)). Because the PTAB used the wrong legal analysis, PO2 and temperature are, in fact, result-effective variables, which are those variables which achieve a recognized result before determination of optimal or workable ranges of that variable might be characterized as routine experimentation.

[A] person of ordinary skill would not always be motivated to optimize a parameter ‘if there is not evidence in the record that the prior art recognized that that particular parameter affected the result.”7

As such, Judge Lourie noted that there was no dispute raised by Synvina that PO2 and temperature were known to affect the claimed oxidation reaction – a reaction which was already known in the prior art at the time of the invention.

Rather, each reference relevant to claims 1-5 expressly disclosed appropriate or preferred temperatures and air pressures for the reaction, indicating that persons of ordinary skill understood that the reaction was affected by temperature and pressure… [I]t cannot be said that []there was essentially no disclosure of the relationship between[] temperature, PO2, and the claimed oxidation reaction. There was such disclosure.8

The Fed Circuit reversed, which means the ‘921 patent is, indeed, obvious, and therefore, invalid. This case also is significant because it affirms the burden-shifting from petitioner to patentee in an IPR proceeding to demonstrate nonobviousness of claimed overlapping ranges through a showing of secondary considerations.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), rev’g DuPont v. Furanix Techs. B.V., No. IPR2015-01838 (Paper No. 43) (P.T.A.B. Mar. 3, 2017). ↩

-

See Jarsolaw Lewkowski, Synthesis, Chemistry and Applications of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural and Its Derivatives, ARKIVOC 17 (2001); Shigeru Oae, A Study of the Acid Dissociation of Furan- and Thiophenediocarboxylic Acids and of the Alkaline Hydrolysis of Their Methyl Esters, 38(8) Soc. Jpn. 1247 (1965). ↩

-

See SAS Inst. Inc. v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct. 350 (2018). The Fed Circuit sua sponte ordered no action taken, see PGS Geophysical AS v. Iancu, 891 F.3d 1354, 1361-63 (Fed. Cir. 2018). ↩

-

See DuPont, supra (slip op. at 15). ↩

-

See In re Wertheim, 541 F.2d 257 (C.C.P.A. 1976); In re Woodruff, 919 F.2d 1575 (Fed. Cir. 1990); Galderma Labs, L.P. v. Tolmar, Inc., 737 F.3d 731, 737-38 (Fed. Cir. 2013). ↩

-

See DuPont, supra (slip op. at 20). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 21), citing In re Antonie, 559 F.2d 618, 620 (C.C.P.A. 1977) ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 22). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent