Fed Circuit Watch: PTAB Bungles Real Party-in-Interest Analysis

On September 7, 2018, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided Worlds Inc. v. Bungie, Inc.,1 representing another case in the growing case law of IPRs and specifically, the time-bar application and collateral estoppel.

Worlds Inc. owns U.S. Patent Nos. 7,945,856 (‘856), 8,082,501 (‘501), and 8,145,998 (‘998). All are directed to methods and systems of computer-generated display of virtual reality avatars, primarily used in video games. In 2012, Worlds filed a patent infringement suit against Activision Publishing, Inc., the world’s largest video game developer and distributor alleging infringement of, among others, its three patents at-issue. In November 2014, Worlds filed notice with the court that it intended to add the video game Destiny as an infringing product to the litigation. Bungie, Inc. is the developer and owner of the Destiny brand and product line, and is distributed by Activision. In 2015, Bungie filed six IPRs against Worlds, including the three that are the subject of this appeal. The IPRs were filed more than one year after Activision was served its complaint in its litigation with Worlds.

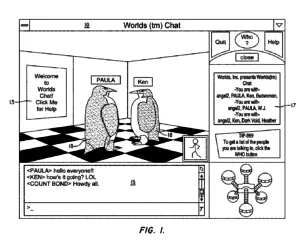

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,945,856 B2, May 17, 2011, to Dave Leahy, Judith Challinger, B/ Thomas Adler, and S. Mitra Ardon (inventors); Worlds.com, Inc. (assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,945,856 B2, May 17, 2011, to Dave Leahy, Judith Challinger, B/ Thomas Adler, and S. Mitra Ardon (inventors); Worlds.com, Inc. (assignee)

During procedural discovery, Worlds discovered that Activision may actually be a real party-in-interest to the proceeding, which would have made the IPRs time-barred under 35 U.S.C. §315(b). Worlds requested additional discovery, and submitted as evidence the DevPub Agreement between Activision and Bungie. However, the PTAB instituted review, rejecting Worlds’ contention that Activision is a real party-in-interest, finding that “Patent Owner has not demonstrated that Activision is an unnamed real party in interest in this proceeding.” In the final written decisions, the PTAB invalidated most of the claims of the patents at-issue under primarily 35 U.S.C. §103. Worlds appeals the underlying procedural issue of real party-in-interest, as well as the substantive obviousness rejections.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Chief Judge Prost, and Judges O’Malley and Taranto, with Chief Judge Prost writing for the court. Chief Judge Prost immediately had issue with the fact the PTAB placed the burden of persuasion on Worlds, as the patent owner, to determine time-bar application under §315(b). Further, she noted that:

Absent from the Board’s analysis of the real-party-in-interest issue is any clear statement of what, if any, burden framework the Board used to analyze the evidence presented in these IPRs, including an identification of which party the Board viewed as bearing the burden of persuasion.2

In general, she agreed that an IPR petitioner’s initial identification of any real party-in-interest should be accepted unless challenged by the patent owner/respondent. Further, she agreed that the patent owner must then produce some evidence to support its real party-in-interest contentions. However, she disagreed that the initial acceptance of the IPR’s identification of the real parties-in-interest as a rebuttable presumption that shifts the burden from the petitioner to the patent owner. She supported this contention by citing the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. §556(d), which governs burden of persuasion in administrative proceedings.

This allocation of the burden of persuasion makes sense. First, it is consistent with the general rule that “[a]bsent some reason to believe that Congress intended otherwise, … we will conclude that the burden of persuasion lies where it usually falls, upon the party seeking relief.”3

Further, the IPR petitioner is usually in a better position, Chief Judge Prost posited, to access the necessary evidence relevant to a real party-in-interest investigation. This position, therefore, necessitates there be no burden-shifting on who is to prove real parties-in-interest; the IPR petitioner raises no real parties-in-interest, which is challenged by the patent owner, who then submits the proper evidentiary support. This support, then, must be refuted by the petitioner, which, being better placed to obtain any evidence of refutation since it already has some relationship with the alleged real party-in-interest. However, she would not go as far as to include a presumption – after all, if the patent owner’s contention that an alleged real party-in-interest is not supported by evidence, it would be insufficient for a dispute on this issue.

Here, Chief Judge Prost noted, that Worlds presented evidence of the DevPub Agreement between Activision and Bungie, and further, supported its contention that Activision was a real party-in-interest by the facts that the intent notice in November 2014 to add Bungie’s product, Destiny, to its litigation between Activision and Worlds, and that five patents at-issue in the litigation were the same patents challenged in IPRs by Bungie.

This case is an extension of the recently decided, and unsealed, opinion in the Applications in Internet Time case where the Fed Circuit clarified the definition of “real party-in-interest,” which the Fed Circuit held that an analysis should be a flexible one, taking into both equitable and practical considerations, to determine whether “the non-party is a clear beneficiary that has a preexisting, established relationship with the petitioner.”4

The Fed Circuit vacated the judgment of the PTAB, and remanded for further proceedings, with the burden shifted to Bungie as the IPR petitioner to show Activision was not a real party-in-interest consistent with this ruling. If Activision is, in fact, a real party-in-interest, then the IPRs should be vacated because collateral estoppel principles prevent the IPRs from being instituted in the first place.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), vacating and remanding, Bungie, Inc. v. Worlds Inc., Case No. IPR2015-01264 (Paper No. 42) (P.T.A.B. Nov. 10, 2016), Case No. IPR2015-01319 (Paper No. 42) (P.T.A.B. Dec. 6, 2016), and Case No. IPR2015-01321 (Paper No. 42) (P.T.A.B. Nov. 28, 2016). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 6). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 8-9). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 17), citing Applications in Internet Time, LLC v. RPX Corp., 897 F.3d 1336, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2018), and Wi-Fi One, LLC v. Broadcom Corp., 887 F.3d 1329, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2018). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent