On August 15, 2018, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued BSG Tech LLC v. Buyseasons, Inc.,[1] which represents one additional case in the §101 jurisprudence. This particular case bears striking resemblance to the Enfish case,[2] where the Fed Circuit upheld software claims directed to a self-referential table in a database, and therefore, patent-eligible under §101, except in this case, the Fed Circuit found similar software claims directed to a database to be patent-ineligible.

The facts are as follows.

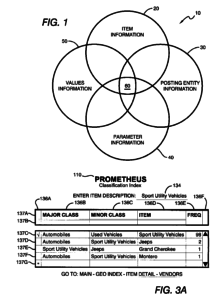

BSG owns U.S. Patent Nos. 6,035,294 (‘294), 6,243,699 (‘699), and 6,195,652 (‘652), all with substantially overlapping specifications and directed to a “self-evolving generic index” for organizing information in a database. BSG’s inventive concept argued that prior art database organized information using various criteria, including classifications, parameters, and search values. BSG’s database taught a “self-evolving” database which enabled users to add new search parameters in description of items, which overcame the shortcomings of the prior art databases.

Claim 1 of the ‘699 patent was one deemed representative:

A method of indexing and retrieving data being posted by a plurality of users to a wide area network, comprising:

providing the users with a mechanism for posting the data as parametrized items:

providing the users with listings of previously used parameters and previously used values for use in posting the data;

providing the users with summary comparison usage information corresponding to the previously used parameters and values for use in posting the data; and

providing subsequent users with the listings of previously used parameters and values, and corresponding summary comparisons usage information for use in searching the network for an item of interest.

(Emphasis added).

Claim 10 of ‘294 recited:

A method of indexing an item on a database, comprising:

providing the database with a structure having a plurality of item classifications, parameters, and values, wherein individual parameters are independently related to individual item classifications, and individual values are independently related to individual parameters;

guiding the user in selecting a specific item classification for the item from the plurality of item classification;

storing the item on the database as a plurality of user-selected item classification/parameter value combinations; and

guiding the user in selecting at least one of (a) the parameters of the combinations by displaying relative historical usage information for a plurality of parameters previously used by other users, and (b) the values of the combinations by displaying relative historical usage information for a plurality of values previously used by other users.

(Emphasis added.)

BSG sued BuySeasons for patent infringement of its patents. BuySeasons moved to dismiss for failure to state a claim (Rule 12(b)(6)) and that the asserted claims were invalid as patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. §101. The district court found that the claims were, indeed, patent-ineligible under §101, stating that the claims “were directed to abstract ideas of considering historical usage information while inputting data.” BSG appealed.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges Reyna, Wallach, and Hughes, with Judge Hughes writing for the court. Judge Hughes noted the similar refrain that §101 provides a patent for one for “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.” Further, he noted that the U.S. Supreme Court Alice holding held that fundamental practices prevalent in the stream of commerce were considered abstract ideas, and therefore, not patentable-eligible subject matter.[3] The focus of the claims must be on a specifically-asserted improvement in computer capabilities, rather than a process that invokes computers as just a tool to employ an abstract idea.[4]

Fed Circuit precedent has held that abstract claims are not saved from a §101 analysis, including being found ineligible, merely because there is a recitation to a computer.[5] Further, a claim can be patent-eligible even if it is rooted in computer technology, but attempts to overcome a problem specific to computer technology.[6] Here, Judge Hughes determined, BSG’s patent claims did not address a specific issue limited to computer technology:

Here, the recited database structure similarly provides a generic environment in which the claimed method is performed. The ‘699 specification makes clear that databases allowing users to post parametized items were commonly used at the time of invention. Thus, the recitation of a database structure slightly more detailed than a generic database does not save the asserted claims at step one.[7]

Further, he noted:

[T]he term “summary comparison usage information” [is recited] very broadly. Its [‘699 patent] specification states “usage” is employed herein in its broadest possible sense to include information relating to occurrence, absolute or relative frequency, or any other data which indicates the extent of past usage with respect to the various choices.[8]

This information could be interpreted as side-by-side, relative or distant information, or any parameter or value that could conceivably be defined as “summary comparison usage information.” In other words, there was no further limitation to the terms to go beyond abstraction.

Judge Hughes noted that the BSG claims were unrelated to database functions, and conceivably could be deemed unrelated to computers alone.

Under the claimed methods, information inputted by users into a database is stored and organized in the same manner as information inputted into conventional databases capable of indexing data as classifications, parameters, and values. The claims do not recite any improvement to the way in which such databases store or organize information analogous to the self-referential table in Enfish or the adaptable memory caches in Visual Memory. While the presentation of summary comparison usage information to users improves the quality of the information added to the database, an improvement to the information stored in a database is not equivalent to an improvement in the database’s functionality.[9]

This case may not be as groundbreaking as the more recent Berkheimer case to the §101 case law, but it is instructive as to how the Fed Circuit is approaching cases as to their patent-eligible subject matter. There are several more §101 cases in the pipeline that should have opinions rendered in the next couple of months that may shed additional light on how the Fed Circuit will employ the Berkheimer rule further to the §101 analysis.

[1] ___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), aff’g Case No. 2:16-cv-00530 (E.D. Tex. Mar. 30, 2017).

[2] See Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

[3] See Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S. Ct. 2347, 2356 (2014).

[4] See 822 F.3d at 1336.

[5] See In re TLI Commnc’ns LLC Patent Litig., 823 F.3d 607, 612-13 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

[6] See DDR Holdings, LLC v. HOtels.com L.P., 773 F.3d 1245, 1257 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

[7] See BSG Tech, supra (slip op. at 9).

[8] Id. (slip op. at 10).

[9] Id. (slip op. at 13).