Fed Circuit Watch: Result-Oriented Claims Not Patent-Eligible

This case is the latest iteration of a protracted litigation between non-practicing entity Interval Licensing and AOL.1 In the current case, Interval Licensing LLC v. AOL, Inc.,2 the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled on July 20, 2018, that a claim that merely recites a result without how to achieve that result was patent-ineligible under 35 U.S.C. §101.

The facts are as follows.

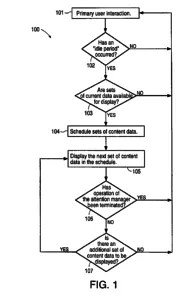

Interval Licensing, through its former name, owns U.S. Patent Nos. 6,034,652 (‘652), entitled “Attention manager for occupying the peripheral attention of a person in the vicinity of a display device,” and directed to a system, method, and computer readable media for displaying data on a computer screen.

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,034,652, Mar. 7, 2000, to Paul A. Freiberger, Golan Levin, David P. Reed, Marc E. Davis, Neal A. Bhadkamkar, Philippe P. Piernot, Todd A. Agulnick, Sally N. Rosenthal, and Giles N. Goodhead (inventors), and Interval Research Corp. (Assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,034,652, Mar. 7, 2000, to Paul A. Freiberger, Golan Levin, David P. Reed, Marc E. Davis, Neal A. Bhadkamkar, Philippe P. Piernot, Todd A. Agulnick, Sally N. Rosenthal, and Giles N. Goodhead (inventors), and Interval Research Corp. (Assignee)

Claim 18 was deemed representative.

- A computer readable medium, for use by a content display system, encoded with one or more computer programs for enabling acquisition of a set of content data and display of an image or images generated from the set of content data on a display device during operation of an attention manager, comprising:

[1] acquisition instructions for enabling acquisition of a set of content data from a specified information source;

[2] user interface installation instructions for enabling provision of a user interface that allows a person to request the set of content data from specified information source;

[3] content data scheduling instructions for providing temporal constraints on the display of the image or images generated from the set of content data;

[4] display instructions for enabling display of the image or images generated from the set of content data;

[5] content data update instructions for enabling acquisition of an updated set of content data from an information source that corresponds to a previously acquired set of content data;

[6] operating instructions for beginning, managing and terminating the display on the display device of an image generated from a set of content data;

[7] content display system scheduling instructions for scheduling the display of the image or images on the display device;

[8] installation instructions for installing the operating instructions and content display system scheduling instructions on the content display system; and

[9] audit instructions for monitoring usage of the content display system to selectively display an image or images generated from a set of content data.

The claim 18 recitations were deemed to read as generic sets of instructions, namely enabling acquisition of content to be displayed, and enabling control over when to display that acquired content. No further limitations were recited in the claim; further, the specification only describes the instructions as conventional. Interval even conceded that the instructions were not inventive, and merely conventional. Interval Licensing sued AOL, and others, for infringement of its ‘652 patent and other patents which were the subject of other litigation. At trial, the district court concluded that the claims lacked inventive concept under §101. Interval Licensing appealed.

The Fed Circuit panel was composed of Judges Taranto, Plager, and Chen, with Judge Chen writing for the court. Judge Chen wrote immediately at the beginning of his opinion:

Claims 15-18 are directed to an abstract idea: the presentation of two sets of information, in a non-overlapping way, on a display screen. The claimed “attention manager,” broadly construed as any “system” for producing that result, is not limited to a means of locating space on the screen unused by the a first set of displayed information and then displaying the second set of information in that space … The claimed limitations … are stated in general terms and do not further define how the attention manager segregates the display of two sets of data on a display screen. Considered as a whole, the claims fail under §101’s abstract idea exception because they lack any arguable technical advance over conventional computer and network technology for performing the recited functions of acquiring and displaying information.3

Judge Chen went through the Alice steps for patent-eligibility. As to step one, whether the claims belong to a judicial exception – law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea – Judge Chen referred to two 19th century patent-eligibility cases. In Wyeth v. Stone, the patent claimed broadly the art of cutting ice. The Court determined that it was “a claim for an art or principle in the abstract, and not for any particular method or machinery,” and held “[n]o man can have a right to cut ice by all means and methods.”4 In O’Reilly v. Morse, the Supreme Court held that a broadly worded claim directed to “electro-magnetism, however developed, for making or printing intelligible characters, letters, or signs, at any distances” was “too broad, and not warranted under the law” (emphasis added).5

Judge Chen determined from these two cases:

[E]ach inventor [] lost a claim that encompassed all solutions for achieving a desired result, whether for cutting ice or for printing at a distance using electromagnetism. In other words, those latter claims failed to recite a practical way of applying an underlying idea; they instead were drafted in such a result-oriented way that they amounted to encompassing the “principle in the abstract” no matter how implemented.6

He pointed out that the attention manager of Claim 18 was merely an abstract concept rather than an improvement over the art of displaying images on devices. Further, the term in its plain construction merely demanded a particular result without further limitation on how to produce that result.

As to step two, or inventive concept beyond the mere abstract idea, Judge Chen found none. He noted the specification neither describes how preexisting background is altered to enable displays of second set of information, nor describes how the two sets of information are separated. Interval Licensing tried to argue that the claims provide an improvement to computer technology by combining acquired information with the user’s primary display. Judge Chen disagreed. Claim 18, he wrote, is so broad that it covers every basic concept of displaying any two sets of information, including information that is organized by generic and conventional means. This is dissimilar to DDR Holdings by not providing a specific solution a computer-related problem.

As such, the panel held Claim 18 was invalid as patent-ineligible subject matter.

Judge Plager concurred-in-part and dissented-in-part. He concurred in affirming the invalidation of the ‘652 patent on §101 grounds, but dissented to voice his displeasure with the state of patent-eligibility case law.

Today we are called upon to decide the fate of some inventor’s efforts, whether for good or ill, on the basis of criteria that provide no insight into whether the invention is good or ill. Given the current state of the law regarding what inventions are patent eligible, and in light of our governing precedents, I concur … . even though the state of law is such as to give little confidence that the outcome is necessarily correct. The law [] renders it near impossible to know with any certainty whether the invention is or is not patent eligible. Accordingly, I also respectfully dissent from our court’s continued application of this incoherent body of doctrine.7

Judge Plager lays the blame of the controversy surrounding the §101 patent-eligibility squarely on the U.S. Supreme Court, especially with its patent law-focused decisions in Alice and Mayo. The judicial exceptions of the Alice/Mayo step one are all judicially-invented, but “abstract idea” does not have a precise definition:

[A] search for a definition of “abstract ideas” in the cases on §101 from the Supreme Court, as well as from this court, reveals that there is no single, succinct, usable definition anywhere available. The problem with trying to define “abstract ideas,” and why no court has succeeded in defining it, is that, as applied to as-yet-unknown cases with as-yet-unknown inventions, it cannot be done except through the use of equally abstract terms.8

Further, the Alice/Mayo step two requires inventive concept definition, for which there is none. He invokes Judge Giles Rich, the father of the modern U.S. patent law, by noting that when drafting the Patent Act of 1952, Judge Rich deliberately included §103 obviousness as a requirement for patentability in order to do away with the “abstractness” of inventive concept. He additionally joined Judges Linn and Lourie in their frustration with the §101 jurisprudence, demanding clarity through congressional intervention.

This case emphasizes the continual flux the state of §101 case law, and particularly in the Fed Circuit since it is the appellate court designated to hear patent cases. While Interval Licensing was probably decided correctly, it belies the fact the only possible solution in fixing the confusion in §101 law is through an act of Congress.

Footnotes

-

Claims 1-4 and 7-15 of the U.S. Patent No. 6,788,314 and claims 4-8, 11, 34-35 of U.S. Patent No. 6,032,652 were invalidated as indefinite. See Interval Licensing LLC v. AOL, Inc., 766 F.3d 1364, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2014), cert. denied, 136 S. Ct. 59 (2015). ↩

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), aff’g 193 F. Supp. 3d 1184, 1190 (W.D. Wash. 2016). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 3). ↩

-

30 F. Cas. 723, 727 (C.C.D. Mass. 1840). ↩

-

56 U.S. 62, 113 (1853). ↩

-

Interval Licensing, supra (slip op. at 12). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 1-2) (Plager, J., concurring-in-part and dissenting-in-part). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 5). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent