Fed Circuit Watch: PTAB Anticipation Analysis All Wrong

Anticipation in patent law means the claimed invention lacks novelty, or is not new; in other words, the invention was already invented.1 Anticipation, as codified in 35 U.S.C. §102(a) (or §102(b) in pre-AIA statute), is the gateway substantive legal analysis which must take place in order to assess patentability of an invention. Therefore, when the analysis is wrong, it can have severe ramifications for the patent holder. Such was the case in the recent ruling from the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, TF3 Ltd. v. Tre Milano, LLC,2 which was decided on July 13, 2018. The Fed Circuit held that the PTAB’s anticipation analysis was incorrect, and more broadly interpreted the claim construction than was defined in the disclosure.

The facts are as follows.

TF3 Ltd. owns U.S. Patent No. 8,651,118 (‘118), entitled “Hair styling device,” and directed to a device that automated hair curling.

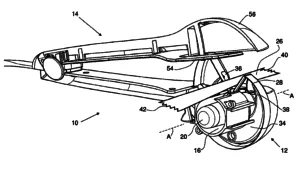

Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,651,118 B2, Feb. 18, 2014, to Alfredo De Benedictis and Mark Christopher Hughes (TF3 Ltd., Assignee)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,651,118 B2, Feb. 18, 2014, to Alfredo De Benedictis and Mark Christopher Hughes (TF3 Ltd., Assignee)

Claim 1 was deemed representative:

- A hair styling device having:

a body defining a chamber adapted to accommodate a length of hair, the chamber having a primary opening through which the length of hair may pass into the chamber;

a rotatable element adapted to engage the length of hair adjacent to the primary opening;

an elongated member around which, in use, the length of hair is wound by the rotatable element, the elongated member having a free end;

the chamber having a secondary opening through which the length of hair may pass out of the chamber, the secondary opening being located adjacent the free end; and

a movable abutment which can engage the length of hair in use, the movable abutment having an open position in which the length of hair can pass through the secondary opening, and a closed position in which the length of hair is retained within the chamber, wherein the moveable abutment is located within one of (i) the secondary opening, (ii) the primary opening, and (iii) a passageway connecting the secondary opening to the primary opening.3

(Emphasis added.)

Tre Milano filed an IPR requesting review of the ‘118 patent, challenging the validity of claims 1-5 and 11 under the grounds that the claims were anticipated by U.S. Patent No. 4,148,330 (“Gnaga”) and/or Japanese Patent Application No. 61-10102 (“Hoshino”).

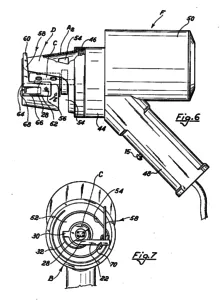

Source: U.S. Patent No. 4,148,330, Apr. 10, 1979, to Vittorio Gnaga

Source: U.S. Patent No. 4,148,330, Apr. 10, 1979, to Vittorio Gnaga

Gnaga, entitled “Motor-curler unit for automatic application of curlers to the hair to be treated,” is directed to a hair curling device where the hair is wound around a rotating curler and heated, with the curler ejecting and disassembling the hair allowing for the hair to unwound from the curler.

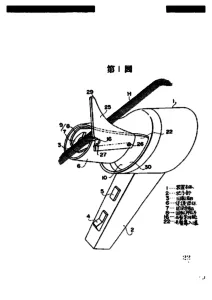

Source: Japanese Utility Model Application No. 61-10102, Jan. 21, 1986, to Koichi Hoshino

Source: Japanese Utility Model Application No. 61-10102, Jan. 21, 1986, to Koichi Hoshino

Hoshino, entitled “Automatic hair curler,” describes a hair curling device where the curler is inserted into a winding structure, while hair is wound around the rotating curler, supported by locking lever and hair guide arm, and then the hair is ejected from the device, disassembled, which allows the curl to be removed by unwinding from the curler.

The PTAB construed “free end” to mean “an end of the elongated member that is unsupported when the movable abutment is in the open position.” The PTAB also did not construe “length of hair can pass through the secondary opening,” because it did not deem it a requirement of claim 1.

The Fed Circuit panel, composed of Judges Newman, Lourie, and Hughes, with Judge Newman writing for a unanimous panel, disagreed with the PTAB’s analysis. As to the “length of hair” term, Judge Newman noted that TF3 indicated the construction should be based on what was in the specification:

It is arranged that the abutment 52 in its open position allows the styled length of hair to pass out of the secondary opening 50, i.e., to slide along the elongate member 20 towards and subsequently off its free end. (Emphasis added.) Little force is required to separate the hair styling device 10 from the length of hair which has been styled … the length of hair is not required to pass any obstruction or otherwise be forced to uncurl during its removal from the hair styling device 10.4

Claims are not read more broadly than the specification, even in spite of the broadest reasonable interpretation standard (BRI) (MPEP 2111). BRI, she wrote, must be reasonable, and read in light of the claims and specification. As such, ‘118 patent describes a hair curling device that improves on curl retention by permitting a formed curl to slide off the end of the elongate member without being uncurled. This structural element is not represented in either the Gnaga or Hoshino devices, noted Judge Newman. She wrote:

[I]t is not reasonable to read the claims more broadly than the description in the specification, thereby broadening the claims to read on the prior art over which the patentee asserts an improvement.5

As to the “free end” term, she observed that the PTAB rejected TF3’s construction, and construed it to mean “an end of the elongate member that is unsupported when the movable abutment is in the open position.” The PTAB did not require support for this construction in the specification. However, this analysis was incorrect according to Judge Newman. The requirement that the “free end” have “structural support” from the abutment is contradicted by what was in the specification. The specification states that the “free end” of the elongate member is located adjacent to the secondary opening. Consequent to this new construction, Judge Newman deemed that the ‘118 patent was not anticipated by either Gnaga or Hoshino.

Because anticipation requires not only each claim element to be in one single reference, all of the elements must be arranged in the same manner as in the claims.6 This was not the case with the ‘118 patent and the two prior art references. The Fed Circuit reversed invalidity based on anticipation.

Footnotes

-

See In re Spada, 911 F.2d 705, 708 (Fed. Cir. 1990). ↩

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), rev’g Tre Milano, LLC v. TF3 Ltd., No. IPR2015-00649 (P.T.A.B. May 2, 2016). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 4). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 9). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 11). ↩

-

See Net MoneyIN, Inc. v. VeriSign, Inc., 545 F.3d 1359, 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2008). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent