Fed Circuit Watch: Every Limitation Required for Infringement-by-Manufacture

In FastShip, LLC v. United States,1 the patented Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) was allegedly infringed. This case is interesting, in part because the defendant was the U.S. Government, and it is a patent infringement suit which arrived to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit by way of the Court of Federal Claims (CFC). Because the U.S. cannot be sued for patent infringement under the normal patent infringement statute, 35 U.S.C. §271, resulting from its sovereign immunity, patent owners are able to take claims against the U.S. before the CFC under 28 U.S.C. §1498, which provides a waiver of sovereign immunity, for manufacture of a patent without license.

The facts are as follows.

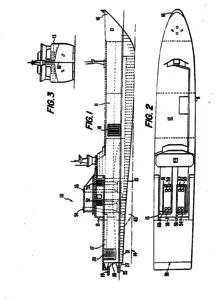

Source: U.S. Patent No. 5,080,032, Jan. 14, 1992, to David L. Giles

Source: U.S. Patent No. 5,080,032, Jan. 14, 1992, to David L. Giles

FastShip owned the U.S. Patent Nos. 5,080,032 (‘032) and 5,231,946 (‘946), entitled “Monohull fast sealift or semi-planing monohull ship,” and directed to a very specific type of fast waterjet-powered military-grade ships. According to FastShip’s complaint, the U.S. Navy’s Freedom-class LCS-1 and LCS-3 ships infringed claims 1 and 19 of the ‘032 patent, and claims 1, 3, 5, and 7 of the ‘946 patent. Both patents expired on May 18, 2010.

The Government filed for motion for partial summary judgment, arguing that the LCS-3 was not manufactured by the U.S. within the meaning of §1498, which the CFC granted. Further, after a bench trial, the CFC found the LCS-1 had been infringed and awarded damages to FastShip. FastShip appealed the summary judgment and damages award calculation.

The Fed Circuit panel, composed of Judges Moore, Wallach, and Chen, with Judge Wallach writing for the court, first addressed the statute at-issue.

1498(a) reads:

Whenever an invention described in and covered by a patent of the United States is used or manufactured by or for the United States without license of the owner thereof or lawful right to use or manufacture the same, the owner’s remedy shall be by action against the United States in the United States Court of Federal Claims for the recovery of his reasonable and entire compensation for such use and manufacture.

Since the patents expired on May 18, 2010, the first issue dealt with whether the LCS-1 and LCS-3 were “manufactured” for purposes of §1498 before the ‘032 and ‘946 patents expired. Judge Wallach noted that the LCS-1 were launched in September 2006, and commissioned by the U.S. Navy in September 2008. The LCS-3 design was started later, and the keel laid in July 2009. The waterjet system was installed in July 2010, and final module erected in September 2010, and testing conducted through 2011. Delivery of a fully operational LCS-3 was made to the U.S. Navy in June 2012.

So, by the expiration date of May 18, 2010, only the LCS-1 was fully complete and in use. The LCS-3 was still under construction. The critical issue revolves around whether enough of the LCS-3 was “manufactured” before the May 18, 2010 date. Judge Wallach first determined the definition of “manufacture” and interpreted in accordance with its “ordinary, contemporary, common meaning.”2 Reviewing the legislative history of §1498, he observed that the definition of “manufacture” was “to make by hand, by machinery, or by other agency” and to work, as raw or partly wrought materials, into suitable forms for use.”3 Further, the ordinary dictionary definition is “to work up material into forms suitable for use,”4 which is also consistent with the U.S. Supreme Court definition of “manufacture” to include “conversion of raw materials by hand, or by machinery, into articles suitable for use of man.”5

Judge Wallach’s analysis then moved to the relevant case law, and he noted in Deepsouth Packing, that:

[T]he Supreme Court considered the “question of manufacture” … and it “could not endorse the view that the substantial manufacture of the constituent parts of a machine constitutes direct infringement when we have so often held that a combination patent protects only against operable assembly of the whole and not the manufacture of its parts.”6

Further, in Paper Converting, infringement could occur “where … significant, unpatented assemblies of elements are tested during the patent term, … testing the assemblies can be held to be in essence testing the patented combination and, hence, infringement.”7 And, in Hughes Aircraft, the CFC determined that “even though test parts were not intended for launch with the spacecraft, the fact remains that the spacecraft had been entirely assembled to the extent feasible at the time” and the “spacecraft in issue was ‘manufactured’ as of the expiration date of the patent.”8 Based on the case law, as well as the ordinary and plain meaning, Judge Wallach determined “manufacture” to mean “such that a product is ‘manufactured’ when it is made to include each limitation of the thing invented and is therefore suitable for use.”9

Applying the definition to the construction history of the LCS-3, Judge Wallach found that LCS-3 was not manufactured by the ‘032 and ‘946 patents’ expiration date. First, the waterjets were only installed in July 2010. Further, the final module, or the full hull, was not complete until August 2010.

As a result, the panel determined that the CFC did not err in granting the Government’s motion for partial summary judgment when the LCS-3 was not manufactured for purposes of §1498, and therefore, did not infringe FastShip’s expired patents. That means, the entire hull of the ship had to have been manufactured, or built, before the expiration of the patents at-issue. The panel further modified the damages award for the LCS-1 infringement, and affirmed the CFC judgment.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), aff’g 122 Fed. Cl. 71 (2015), and 131 Fed. Cl. 592 (2017). ↩

-

See Sandifer v. U.S. Steel Corp., 134 S. Ct. 870, 876 (2014); see also MPEP 2111.01 and MPEP 2173. ↩

-

See FastShip, supra (slip op. at 8). ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 9), citing Samsung Elecs. Co. v. Apple Inc., 137 S. Ct. 429, 435 (2016). ↩

-

See Deepsouth Packing Co. v. Laitram Corp., 406 U.S. 518, 528 (1972). ↩

-

See Paper Converting Mach. Co. v. Magna-Graphics Corp., 745 F.2d 11, 19-20 (Fed. Cir. 1984). ↩

-

See Hughes Aircraft Co. v. U.S., 29 Fed. Cl. 197, 220 (1993). ↩

-

See FastShip, supra (slip op. at 14). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent