Fed Circuit Watch: Innovative Abstract Idea is Still Abstract Idea

On May 15, 2018, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed down SAP America, Inc. v. InvestPic, LLC.1 The patent at-issue, U.S. Patent No. 6,349,291 (‘291) was directed to systems and methods for performing statistical analyses of investment information. In other words, the ‘291 patent claimed subject matter that was merely an innovative use of data in the financial sector. Put another way, the ‘291 patent is just an innovative abstract idea. And, according to the Fed Circuit, an innovative abstract idea is still an abstract idea. Therefore, it is patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. §101.

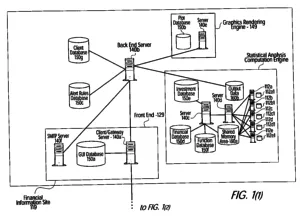

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,349,291, Feb. 19, 2002, to Samir Varma

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,349,291, Feb. 19, 2002, to Samir Varma

The facts are as follows.

The ‘291 patent’s claims were subject to two ex parte reexamination under 35 U.S.C. §302 proceedings before the PTAB, where the consolidated case was heard before the Fed Circuit in 2016. The Fed Circuit vacated the PTAB’s cancellation of the ‘291 patent claims under 35 U.S.C. §102 and 35 U.S.C. §103.2 SAP filed a subsequent declaratory judgment action against InvestPic, alleging the ‘291 patent claims were ineligible under §101. When SAP moved for JMOL, the district court granted the motion, holding all ‘291 claims ineligible and therefore invalid.

The Fed Circuit panel, composed of Judges Lourie, O’Malley, and Taranto, with Judge Taranto writing for the court, affirmed. He flatly expressed, “a claim for a new abstract idea is still an abstract idea.”3 Even if a claimed invention passes the novelty requirement under §102 and the nonobviousness requirement under §103, it must also pass the subject matter-eligibility requirements under §101. He stated:

The claims here are ineligible because their innovation is an innovation in ineligible subject matter. Their subject is nothing but a series of mathematical calculations based on selected information and the presentation of the results of those calculations (in the plot of a probability distribution function). No matter how much of an advance in the finance field the claims recite, the advance lies entirely in the realm of abstract ideas, with no plausibly alleged innovation in the non-abstract application realm. An advance of that nature is ineligible for patenting.4

The Alice test requires a two-step process. First, the claims are first read as directed to a patent-ineligible concept. If so then, second, claim elements are analyzed whether there is an inventive concept sufficient to transform the claimed invention into something more than just an abstract idea.5 Judge Taranto stated perfunctorily that the ‘291 subject matter was an abstract idea:

The claims in this case are directed to abstract ideas. The focus of the claims, as is plain from their terms, [] is on selecting certain information, analyzing it using mathematical techniques, and reporting or displaying the results of the analysis. That is all abstract.6

Judge Taranto took steps to distinguish this case from McRO and Thales Visionix. The McRO claims were directed to creating a physical medium, rather than this case which merely improves something abstract. Specifically, the McRO claims were directed to display of lip synching and facial expressions.7 Here, the claims are just directed to an improvement of a mathematical technique (i.e., Gaussian distribution) with no improved display mechanism. Further, the Thales Visionix claims were directed to an improved physical tracking system.8 Here, it is selecting and analyzing math information, then displaying it – basically, an improved abstract idea.

As for the second step, Judge Taranto analyzed the claims for something more than just the abstract idea itself. He noted that the dependent claims discussed further limitations of in statistical modeling, including the bootstrap method, jackknife method, and cross-validation method. However, he further noted that these methods were all just rehashed resampling methods, and the claims only narrowed existing, abstract mathematical operations.

Judge Taranto concluded his opinion with:

There is, in short, nothing “inventive” about any claim details, individually or in combination, that are not themselves in the realm of abstract ideas. In the absence of the required “inventive concept” in application, the claims here are legally equivalent to claims simply to the asserted advance in the realm of abstract ideas – an advance of mathematical techniques in finance … . An innovator who makes such an advance lacks patent protection for the advance itself. If any such protection is to be found, the innovator must look outside patent law in search of it, such as in the law of trade secrets, whose core requirement is that the idea be kept secret from the public.9

This case is consistent with the §101 post-Alice jurisprudence. In a larger view, this case represents a validation of the underlying principles of Alice. It should be noted that InvestPic is a non-practicing entity (NPE, or patent assertion entity, PAE), without a commercial website and only one employee, Samir Varma, who is the inventor of the ‘291 patent. On one hand, the system should protect legitimate patent holders from frivolous patent litigants. However, on the other hand, this case also represents the continued turmoil that the courts have wrought on the stability of patent rights in America. With the Berkheimer/Aatrix en banc petitions pending (and also possible petitions for writ of certiorari), the landscape is still filled with §101 land mines that will continue to plague patent owners in this country until either Congressional or U.S. Supreme Court intervention is made.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), aff’g SAP Am., Inc. v. InvestPic, LLC, 260 F. Supp. 3d 705 (N.D. Tex. 2017). ↩

-

See In re Varma, 816 F.3d 1352, 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2016). ↩

-

See Synopsis, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1151 (Fed. Cir. 2016). ↩

-

See SAP, supra (slip op. at 3). ↩

-

See Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S. Ct. 2347, 2355 (2014). ↩

-

See SAP, supra (slip op. at 8). ↩

-

See McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America Inc., 837 F.3d 1299, 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2016). ↩

-

See Thales Visionix Inc. v. United States, 850 F.3d 1343, 1348-49 (Fed. Cir. 2017). ↩

-

See SAP, supra (slip op. at 13). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent