Fed Circuit Watch: Merck’s Unclean Hands Render Hep C Patents Unenforceable

The doctrine of unclean hands is a judicially-created equitable defense in which equitable relief is denied where that party has acted in a fraudulent manner or in bad faith.1 Gilead Scis., Inc. v. Merck & Co., Inc.,2 decided by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on April 25, 2018, discusses the confluence of patent prosecution and inequitable misconduct. In this case, it did not work out too well for Merck, which found two of its patents for treating hepatitis C found unenforceable due to misconduct on the part of one of its patent attorneys.

The facts are as follows.

Merck owns U.S. Patent Nos. 7,105,499 (‘499) and 8,481,712 (‘712). Both patents are entitled “Nucleoside derivatives as inhibitors of RNA-dependent RNA viral polymerase,” and directed to compounds used to treat RNA viral infection, namely, hepatitis C. Both are similar to the compound sofosbuvir, the active ingredient in the hepatitis C drugs SOVALDI® and HARVONI®, both owned by Gilead. Gilead sought declaratory relief against Merck, alleging the ‘499 and ‘712 patents were invalid, and Gilead was not infringing the patents. The district court found unclean hands resulting from Merck’s business misconduct and litigation misconduct, and ruled for Gilead, barring Merck from asserting its patents against Gilead. Merck appealed.

The chemical structures at-issue involve a certain combination within a Markush group claimed in the ‘499 patent which have 1) a single-ring base, 2) a methy (C1 alkyl) in the R1 position, and 3) a fluoro in the R2 or R3 position. A subgenus of this specific characteristic is part of Gilead’s sofosbuvir compound, disclosed in its U.S. Patent No. 7,429,572 (‘572), for “Modified fluorinated nucleoside analogues.”

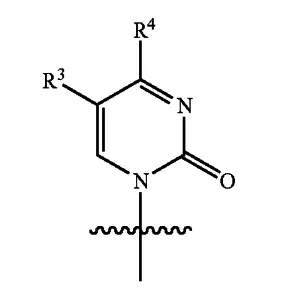

The ‘572 patent discloses the following stereochemical structure for the pyrimidine base as:

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,429,572 B2, Sept. 30, 2008, to Jeremy Clark (Pharmasset, Inc.)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,429,572 B2, Sept. 30, 2008, to Jeremy Clark (Pharmasset, Inc.)

Where R3 is H and R4 is NH2 or OH.

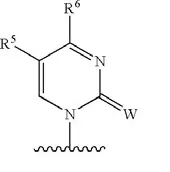

The ‘499 patent discloses the following stereochemical structure:

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,105,499, Sept. 12, 2006, to Steven S. Carroll, et al. (Merck)

Source: U.S. Patent No. 7,105,499, Sept. 12, 2006, to Steven S. Carroll, et al. (Merck)

Where W is O or S, and R5 and R6 are alkyls.

The Federal Circuit panel was composed of Judges Taranto, Clevenger, and Chen, with Judge Taranto writing for the court. Evidence of the two types of misconduct were raised during the district court trial. Merck’s misconduct centered around the activities of one of its patent attorneys, Dr. Phillipe Durette. The business misconduct originated from Merck’s collaboration conversations with Pharmasset, the pharmaceutical company that actually developed the PSI-6130 sofosbuvir compound that became the subject matter of its hepatitis C drug patents. One of Merck’s patent attorneys was involved in the Merck-Pharmasset conversations, in spite of a firewall in place between the two companies. Pharmasset was later acquired by Gilead, including its hepatitis C patent applications. The panel noted:

Dr. Durette [the Merck patent attorney] learned of Pharmasset’s PSI-6130 structure by participating, at Merck’s behest, in a conference call with Pharmasset representatives, violating a clear “firewall” understanding between Pharmasset and Merck that call participants not be involved in related Merck patent prosecutions. Second, Merck continued to use Dr. Durette in related patent prosecutions even after the call. The district court also found, with adequate evidentiary support, a direct connection to the ultimate patent litigation involving sofosbuvir. Thus, Dr Durette’s knowledge of PSI-6130, acquired improperly, influenced Merck’s filing of narrowed claims, a filing that held the potential for expediting patent issuance and for lowering certain invalidity risks. Those findings establish serious misconduct, violating clear standards of probity in the circumstances, that led to the acquisition of the less risky ‘499 patent and, thus, was immediately and necessarily related to the equity of giving Merck the relief of patent enforcement it seeks in this litigation.3

As to the litigation misconduct, the Fed Circuit panel found that there was ample evidence to support the district court’s finding. First, Dr. Ducette gave testimony in a deposition that he was not a participant in the conference call between Merck and Pharmasset, which Merck later conceded was false. Second, Dr. Ducette during trial, made false statements during his testimony when confronted with evidence that he made narrowing claim amendments to the ‘499 patent application after one of Pharmasset’s sofosbuvir patent applications published, and making those amendments with prior knowledge based on the conference call. Judge Taranto noted that the district court found:

[Dr. Durette’s testimony] so incredible as to be intentionally false. The intentional testimonial falsehoods qualify as the kind of misconduct that can, in these circumstances, support a determination of unclean hands. The court also found, with adequate evidentiary support, that the false testimony, in both respects, bore on the origin story of the February 2005 amendment, which was relevant to the invalidity issues in the litigation and hence immediately and necessarily related to the equity of the patent-enforcement relief Merck seeks in this case.4

The Fed Circuit panel found the district court did not abuse its discretion in applying the unclean hands doctrine, it affirmed its judgment. Merck will likely seek en banc petition, but it is doubtful that it could win, given the well-document evidence finding for both business and litigation misconduct. This is probably an egregious example of ethical violations in a patent prosecution; it is really the anomaly out of the thousands upon thousands of patent applications prosecuted each year. Dr. Durette’s actions would certainly have him sanctioned, or worse, disbarred, by either or both the USPTO’s Office of Enrollment and Discipline (OED) and the relevant state bar in which he is admitted to.

However, do not feel too happy for Gilead, either. They were recently criticized for charging over $85,000 for its hepatitis C regimen, which includes the SOVALDI® and HARVONI® drugs.

Footnotes

-

See Kevin Mack, Reforming Inequitable Conduct to Improve Patent Quality: Cleansing Unclean Hands, 21 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 147, 150 (2006). ↩

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018) (slip op.), aff’g No. 13-cv-04057-BLF, 2016 WL 3143943 (N.D. Cal. Jun. 6, 2016). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 16). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 22-23). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent