SCOTUS Watch: IPRs Do Not Violate Article III or Seventh Amendment

Article III of the U.S. Constitution states:

The judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.1

Also, the Copyright and Patent Clause of the U.S. Constitution states:

The Congress shall have power … [t]o promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.2

Therefore, Congressional authority to create and maintain the judicial system cannot exceed this Constitutional grant. Likewise, patent and copyright registrations are mandated by Congressional authority, or delegation of that authority. This is the start of the majority opinion in Oil States Energy Servs., LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group, LLC,3 which the United States Supreme Court decided on April 24, 2018. The decision was specifically narrow, only applying to the constitutionality of the inter partes review (IPR) system of the PTAB, the adjudicatory wing of the USPTO. In this respect, Oil States will have a more limited impact on patent law and practice.

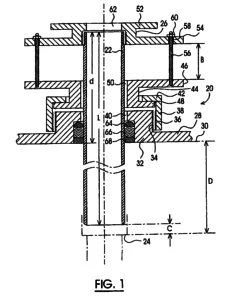

Oil States and Greene’s Energy Services both are oil service companies. Oil States owns U.S. Patent No. 6,179,053 (‘053), directed to hydraulic fracking head equipment protection.

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,179,053, Jan. 30, 2001, to L. Murray Dallas

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,179,053, Jan. 30, 2001, to L. Murray Dallas

In 2012, Oil States sued Greene’s Energy for patent infringement of the ‘053 patent. Greene’s Energy countered by challenging the ‘053 validity. Greene’s Energy also initiated an IPR, arguing that two claims were unpatentable as anticipated. The PTAB, after determining a reasonable likelihood that the two claims were unpatentable and instituting an IPR, found the claims unpatentable as anticipated. The companion district court action’s claim construction, however, found differently. Oil States appealed to the Federal Circuit, which summarily affirmed the PTAB’s decision. Oil States then sought petition for writ of certiorari, arguing that IPRs violate the Article III judicial mandate, or alternatively, the Seventh Amendment right to jury trial.

Justice Thomas began the majority opinion, which was signed on by Justices Kennedy, Ginsburg, Breyer, Alito, Sotomayor, and Kagan, with a historical recitation of the adversarial proceedings before the USPTO.

Congressional authority for post-grant administrative reviews of patents began in 1980, with the advent of ex parte reexaminations (MPEP 2209). This continued with inter partes reexaminations in 1999, where any party could file a petition (MPEP 2609). In both, after the USPTO could initiate a proceeding if a “substantial new question of patentability” arose with a patent claim. Inter partes reexams were abolished by the AIA in 2011, and replaced by IPRs (35 U.S.C. §311).4 The standard of review for claims in an IPR is “reasonable likelihood that petitioner will prevail with respect to at least one claim challenged.” If so, the IPR petition is granted, and an IPR is instituted. The PTAB then reviews the patent’s validity, and issues a final written decision the challenged claims’ patentability. If either party is dissatisfied, the PTAB’s decision can appealed to the Federal Circuit. Oil States’ legal concerns lie in the PTAB’s authority to strip a patent’s validity.

Justice Thomas discussed two older precedents, McCormick Harvesting and Brown v. Duchesne, that were cited by Oil States in support of its argument. However, Justice Thomas noted that “patents only convey a specific form of property right – a public franchise.”5 As such, “a patentee’s rights are ‘derived altogether’ from statutes, ‘are to be regulated and measured by these laws, and cannot go beyond them’.”6 While McCormick held that the courts were the only competent authority to invalidate or correct a patent,7 Justice Thomas disregarded this, stating that McCormick was written during the Patent Act of 1870 which did not contemplate post-grant proceedings, and a reading of McCormick, or any precedent dealing with patents at the time, should be understood as only a reading of the statutory scheme in place at that time, and not one that could transposed to the modern AIA (i.e., current patent law).

Congressional authority for post-grant proceedings like IPRs, Justice Thomas wrote, is based on the public rights doctrine, which followed a long line of Supreme Court precedence.8 This essentially, according to Justice Thomas’ line of analysis, designates patents as public franchises:

By “issuing patents,” the [US]PTO “takes from the public rights of immense value, and bestows them upon the patentee.”9 Specifically, patents are “public franchises” that the Government grants “to the inventors of new and useful improvements.”10 This franchise gives the patent owner the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States. That right did not exist in common law.11

Justice Thomas supported this contention by stating that Congress, through its grant power, can authorize other branches of government, namely, the Executive Branch, to grant patents that meet certain statutory requirements. This, in turn, is delegated to the Director of the USPTO.12 He noted the majority opinion was decidedly narrow in its scope, limited to the constitutionality of IPRs. Justice Thomas specifically noted that infringement suits are not covered by the opinion, which are still, arguably, the domain of Article III courts. Further, he left open a roadmap for future challenges, which include the constitutionality of retroactive application of IPRs, and any issues under the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process13 or Takings Clauses.14

Justice Thomas’ final argument was that IPRs did not violate Seventh Amendment, which he did so simply stated in one paragraph:

The Seventh Amendment preserves the “right of trial by jury” in “Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars.”15 This Court’s precedents establish that, when Congress properly assigns a matter to adjudication in a non-Article III tribunal, “the Seventh Amendment poses no independent bar to the adjudication of that action by a nonjury factfinder.” (Emphasis added.)16

Notwithstanding, his Seventh Amendment analysis here is a bit timid.

Justice Breyer concurred, joined by Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor. He wrote a one-pager with:

I join the Court’s opinion in full. The conclusion that inter partes review is a matter involving public rights is sufficient to show that it violates neither Article III nor the Seventh Amendment. But the Court’s opinion should not be read to say that matters involving private rights may never be adjudicated other than by Article III courts, say, sometimes by agencies.17

(Emphasis added.)

Justice Gorsuch dissented, joined by Chief Justice Roberts. He opened his dissent with:

After much hard work an no little investment you devise something you think truly novel. Then you endure the further cost and effort of applying for a patent, devoting maybe $30,000 and two years to that process a lone. At the end of it all, the Patent Office [i.e., USPTO] agrees your invention is novel and issues a patent. The patent affords you exclusive rights to the fruits of your labor for two decades. But what happens if someone later emerges from the woodwork, arguing that it was all a mistake and your patent should be canceled? Can a political appointee and his administrative agents, instead of an independent judge, resolve the dispute? The Court says yes. Respectfully, I dissent.18

Justice Gorsuch’s dissent had limited case law analysis and was more a policy position paper on private property rights supported by numerous references to Old English common law. He delved into the 18th century England, and old pre-modern U.S. Patent Act, practice of scire facias, the judicial writ of equity which annulled patents. This concept was essentially abolished by the U.S. Supreme Court in Mowry v. Whitney, which concluded that scire facias actions in courts of equity would “seriously impair the value of the title which the government grants after regular proceedings before officers appointed for the purpose if the validity of the instrument by which the grant is made can be impeached by anyone whose interest may be affected by it.”19 Notably, Justice Gorsuch fails to mention this case in his dissent. The reason could be Mowry’s holding directly counters his argument that the government should not have a role in voiding or invalidating patents.

Like Justice Thomas in the majority opinion, Justice Gorsuch also cites McCormick Harvesting in his dissent:

It has been settled by repeated decisions of this court … [a patent] has become the property of the patentee, and as such is entitled to the same legal protection as other property.20

However, as Justice Thomas noted, McCormick was written under the Patent Act of 1870, when IPRs, or even reexaminations, were not part of the patent system.

Neither Justices Thomas nor Gorsuch made a really convincing argument for their respective sides on this debate. Going through the opinions, if it were not for the case headings at the top of the pages, a casual reader would not have noticed that the two justices were writing on the same case. Justice Thomas was focused on this concept of public franchises, and, by extension, the constitutionality of IPRs, while Justice Gorsuch was more interested in discussing private property rights. Neither really addressed non-Article III fora for legal decisions. This would have a huge impact on other administrative agencies which have arguable Article III jurisdictions, namely the International Trade Commission, which can find patents invalid under its trial mandate under 19 U.S.C. §337. For certain, Oil States is more about maintenance of the status quo; the PTAB remains as an institution to determine validity of questionable patents. In the long-term, however, the constitutional issues will percolate back to the Supreme Court once again, especially will opaque references to Due Process and Takings issues made in the opinion.

Footnotes

-

U.S. Const., Art. III, Sec. 1. ↩

-

U.S. Const., Art. I, Sec. 8. ↩

-

584 U.S.___ (2018) (slip op.), cert. granted, 582 U.S.___, 198 L. Ed. 2d 677 (2017), aff’g, 639 Fed. Appx. 639 (2016). ↩

-

Other post-grant administrative proceedings authorized by the AIA include post-grant reviews under 35 U.S.C. §321 and covered business method reviews under 37 C.F.R. §42.300. ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 10). ↩

-

Id. (citing Brown v. Duchesne, 19 How. 183, 195 (1857). ↩

-

See McCormick Harvesting Machine Co. v. Aultman, 169 U.S. 606, 609 (1898). ↩

-

See United States v. Duell, 172 U.S. 576, 582-83 (1899). ↩

-

See United States v. American Bell Telephone Co., 128 U.S. 315, 370 (1888). ↩

-

See Seymour v. Osborne, 11 Wall. 516, 533 (1871); accord Pfaff v. Wells Elects., Inc., 525 U.S. 55, 63-64 (1998). ↩

-

See Oil States, supra (slip op. at 7). ↩

-

In dicta, Justice Thomas also noted that the Director has delegated the responsibility of reviewing patents post-grant to the PTAB (see, slip op. at 3, citing37 C.F.R. §42.108(c)). ↩

-

“No person shall … be deprived … without due process of law … . “ ↩

-

“[N]or shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” ↩

-

U.S. Const., 7th Amend. ↩

-

See Granfinanciera S.A. v. Nordberg, 492 U.S. 33, 53-54 (1989). ↩

-

See Oil States, supra (slip op. at 1) (Breyer, J., concurring). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 1) (Gorsuch, J., dissenting). ↩

-

See Mowry v. Whitney, 81 U.S. 14 Wall. 434, 440-41 (1871). ↩

-

Oil States, supra (slip op. at 9) (Gorsuch, J., dissenting) (citing McCormick Harvesting, 169 U.S. at 608-09). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent