Fed Circuit Watch: Knowles Déjà Vu as PTAB Not (Necessarily) Bound to Prior Court Claim Construction

In a case of déjà vu, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed down Knowles Electronics LLC v. Iancu,1 on April 6, 2018. This case bears striking resemblance to an earlier-issued case this term, Knowles Electronics LLC v. Cirrus Logic, Inc., of which the issues were previously discussed on this blog. The panels were almost identical, with Judges Wallach and Newman sitting for both, and Judge Chen sitting in the Cirrus Logic case and Judge Clevenger sitting on the current one. Judge Wallach wrote the majority opinion in both; Judge Newman dissented in both. Additionally, the issue was very similar in both cases, namely, recognition of the PTAB’s role in construing an already-litigated claim term.

Knowles appealed an inter partes reexamination decision of the PTAB (same as the first case) affirming the final rejection of the Examiner of claims 1-2, 5-6, 9, 11-12, 15-16, and 19 as unpatentable as anticipated (MPEP 2132, same as first case) and claims 21-23 and 25-26 as unpatentable as obvious (MPEP 2141, not the same as first case) of Knowles’ U.S. Patent No. 8,018,049 (‘049) (different patent at-issue than first case). The ‘049 patent, “Silicon Condenser Microphone and Manufacturing Method,” discloses a silicon condenser microphone apparatus, and includes a housing element to shield a hearing aid transducer to protect it from external interference. The shielding is termed a “package,” similar to the housing element of the ‘231 patent of the earlier Knowles case.

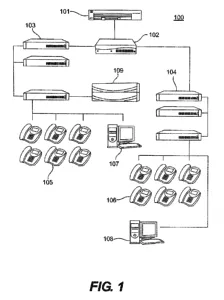

Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,018,049, Sept. 13, 2011, to James J. Allen, Jr., et al.

Source: U.S. Patent No. 8,018,049, Sept. 13, 2011, to James J. Allen, Jr., et al.

Claim 1 was deemed representative:

A silicon condenser microphone package comprising:

a package housing formed by connecting a multi-layer substrate comprising at least one layer of conductive material and at least one layer of non-conductive material, to a cover comprising at least one layer of conductive material;

a cavity formed within the interior of the packaging housing;

an acoustic port formed in the package housing; and

a silicon condenser microphone die disposed within the cavity in communication with the acoustic port;

where the at least one layer of conductive material in the substrate is electrically connected to the at least one layer of conductive material in the cover to form a shield to protect the silicon condenser microphone die against electromagnetic interference.

(Emphasis added.)

The Fed Circuit has long held that the specification and the file history are intrinsic evidence that governs the PTAB’s construction of a claim term. Review of substantial evidence is employed where the PTAB uses extrinsic evidence, like experts, dictionaries, or treatises, and where the PTAB favors one conclusion over “two inconsistent conclusions [that] may reasonably be drawn from the record,”2 substantial evidence must be reviewed upon appeal.

The PTAB construed “package” as “a structure consisting of a semiconductor device, a first-level interconnect system, a wiring structure, a second-level interconnection platform, and an enclosure that protects the system and provides the mechanical platform for the sublevel,” which was broad enough to cover a transducer assembly.3 Knowles argued that “package” was defined as “a second-level connection with a mounting mechanism.”4 This argument was similar to its argument in the first case.

The panel’s majority took the view that the PTAB did not necessarily need to follow prior Fed Circuit precedence in claim construction:

We have held that, in some circumstances, previous judicial interpretations of a disputed claim term may be relevant to the PTAB’s later construction of the same disputed term.5 While the [PTAB] is not generally bound by a previous judicial interpretation of a disputed claim term[, this] does not mean … that it has no obligation to acknowledge that interpretation or to assess whether it is consistent with BRI of the term.6

Notwithstanding, here, Judge Wallach acknowledged that the PTAB did, in fact, note the similarities with the claim term in the prior litigation, MEMS Tech. Berhad v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, where it actually construed the term consistent with that case:

The addition of “or other system” used to evaluate the disputed claims in MEMS Technology comports with the construction of “package” with a broad “second-level connection” as adopted by the PTAB in this case.7

Judge Newman dissented, although for different reasons than she did in the first case. She was concerned with the procedural mechanism on how the case arrived to the Fed Circuit. Because Analog Devices did not defend the case on appeal (since the PTAB had ruled in its favor), the USPTO, through the Director, is allowed to intervene on behalf of the PTAB’s decision. Judge Newman had issues with the USPTO intervening because she believed it violated Article III standing – namely, the USPTO did not have a “justiciable case or controversy.” However, Judge Wallach countered that prior Fed Circuit precedence allowed for it.8

Judge Newman was further concerned with the USPTO’s introduction of new evidentiary support in the form of the textbook and other reference definitions for “package” in a Supplemental Appendix filed by the Director after Analog Devices dropped out of the case. She believed the proper mechanism for introducing new evidence was to request remand back to PTAB.9

The two Knowles cases highlight the importance of patent drafting. The ‘049 specification, similar to the ‘231 specification in the first case, suffered from a poorly written description, in that there was an absence of a definition for “package,” which, if there had been a proper limiting definition in the specification, the PTAB may well have held differently – that is, in favor of Knowles in two cases. Now, it must deal with the aftermath of having two of its patents invalidated due to bad drafting.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018), aff’g Analog Device, Inc. v. Knowles Elecs. LLC (Analog Devices I), No. 2015-004989, 2015 WL 5144183 (PTAB Aug. 28, 2015). ↩

-

See Elbit Sys. of Am., LLC v. Thales Visionix, Inc., 881 F.3d 1354, 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2018). ↩

-

See Knowles, supra (slip op. at 9). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 8). ↩

-

See Power Integrations, Inc. v. Lee, 797 F.3d 1318, 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2015). ↩

-

See Knowles, supra (slip op. at 10-11). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 11). ↩

-

See, e.g., NFC Tech., LLC v. Matal, 871 F.3d 1367, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2017); In re Nuvasive, Inc., 842 F.3d 1376, 1379 n.1 (Fed. Cir. 2016). ↩

-

See Knowles, supra (slip op. at 12-13) (Newman, J., dissenting). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent