This, unfortunately, was a bad week for Steuben Foods, Inc., since this is the second case it lost at the Federal Circuit against the same adversary, Nestlé Foods. This time, in Nestle USA, Inc. v. Steuben Foods, Inc.,[1] the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, on March 13, 2018, ruled that Steuben Foods could not change the construction of a claim term because Steuben Foods itself had already defined the term in the specification. Therefore, Steuben Foods’ patent was found unpatentable as obvious.

The facts are as follows.

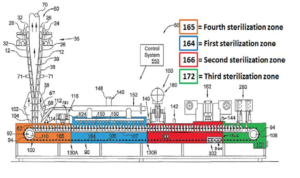

Steuben Foods owns U.S. Patent No. 6,475,435 (‘435), directed to aseptic packaging apparatus for food sterilization tunnels. Claim 1 was deemed representative.

- Apparatus comprising:

a sterilization tunnel for surrounding a plurality of containers with pressurized gas; and

a plurality of zones within the sterilization tunnel having different sterilant concentration levels therein wherein the sterilant concentration levels in the plurality of zones are maintained at a ratio of at least about 5 to 1.

(Emphasis added.)

Specifically, the ‘435 patent discloses an apparatus and method for providing sterilization zones in aseptic sterilization tunnel surrounding containers of pressurized gas. The gas, specifically hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as the sterilant, is split into different zones depending on the H2O2 concentration. It is illustrated below:

The panel, composed of Judges Dyk, Reyna, and Hughes, with Judge Hughes writing for the panel, began with a recitation of the law of obviousness. Obviousness is a question of law, based on underlying facts that include whether a POSITA would have been motivated to combine references and any other relevant indicia of nonobviousness.[2]

Steuben Foods did not agree with the PTAB’s construction of “sterilant concentration levels,” which used a broadest reasonable interpretation[3] standard and defined it as a measurement at any point within the sterilization tunnel. Steuben Foods contended that the “sterilant concentration levels” should have been construed as “the amount of sterilant in the volume of pressurized gas within the zone.”

The panel disagreed. Steuben Foods’ interpretation was limited to a specific embodiment disclosed in the specification. However, the panel noted that the specification had a broader definition, which included “zones with different concentration levels of gas laden sterilant.” As such, under BRI, “sterilant concentration levels” must include sterilant levels found not only in residual amounts left in the bottles but also that released into the air (i.e., gas laden) still within the “plurality of zones” as written in Claim 1. Therefore, the panel found the PTAB’s interpretation not erroneous and upheld unpatentability as obvious.

Normally, patent practitioners make use of lexicography, and is even spelled out in the MPEP rules.[4] If terms are not defined in the specification, then it will be given its ordinary and plain meaning.[5] However, it is also true that the claim language can be broader than what the specification has defined for that term.[6] So, as is the case here, if the term has limitations based on the specification, then the patent owner cannot rebut that definition with a different definition. This is just a word of caution when drafting a patent application, that it is important to maintain consistency with the claim terms and their definitions.

[1] ___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018), vacating and remanding Nestlé USA, Inc. v. Steuben Foods, Inc., Case No. IPR2015-00249 (PTAB 2015).

[2] See Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 839 F.3d 1034, 1047-48 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (en banc).

[3] See MPEP 2111: “claims must be given their broadest reasonable interpretation in light of the specification.”

[4] See MPEP 2111.01(IV): “an applicant is entitled to be their own lexicographer and may rebut the presumption that claim terms are to be given their ordinary and customary meaning by clearly setting forth a definition of the term that is different from its ordinary and customary meaning in the specification at the time of filing.”

[5] See MPEP 2111.01(III): “the ordinary and customary meaning of a claim term is the meaning that would have to a person of ordinary skill in the art in question at the time of the invention.”

[6] See MPEP 2111.01(II): “a particular embodiment appearing in the written description may not be read into a claim when the claim language is broader than the embodiment.”