Fed Circuit Watch: PTAB Not Bound by Fed Circuit Precedent

On March 1, 2018, in a fairly convoluted and highly fractured decision, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) was not bound to collateral estoppel principles which form a long line of Fed Circuit case precedence. That case is Knowles Elecs. LLC v. Cirrus Logic, Inc.1

The facts are as follows.

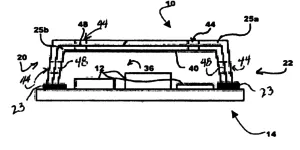

Knowles Electronics owns U.S. Patent No. 6,781,231 (‘231), for “Microelectromechanical System Package with Environmental and Interference Shield,” which discloses a microelectromechanical system (MEMS) package comprising a substrate, microphone, and a cover. The claims are directed to a package shield which protects the microphone from interference or other environmental hazards, and is a purported improvement by addressing certain manufacturing issues regarding these types of microchip housing.

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,781,231, August 24, 2004 to Anthony D. Minervini

Source: U.S. Patent No. 6,781,231, August 24, 2004 to Anthony D. Minervini

Cirrus and several other third-parties filed a request for reexamination of the ‘231 patent. Upon final rejection by the Examiner of claims 1-4 for anticipation2 (MPEP 2132) and proposed claims 23-27 for lack of written description (MPEP 2163),3 the PTAB affirmed. Claims 1-4 and proposed claims 23-27 were at-issue on appeal.

Claim 1 was deemed representative.

A microelectromechanical system package comprising:

a microelectromechanical system microphone;

a substrate comprising a surface for supporting the microelectrochemical microphone;

a cover comprising a conductive layer having a center portion bounded by a peripheral edge portion; and

a housing formed by connecting the peripheral edge portion of the cover to the substrate, the center portion of the cover spaced from the surface of the substrate to accommodate the microelectrochemical system microphone, the housing including an acoustic port for allowing an acoustic system microphone wherein the housing provides protection from an interference signal.

(Emphasis added.)

Claims 2-4 recite a “package,” while proposed claims 23-27 recite a package with a “lower surface comprising a plurality of solder pads” that is “configured to mechanically attach and electrically connect the MEMS package” to a printed circuit board “using a solder reflow process.”4

On appeal, there were issues with the common definition5 of “package,” which Knowles argued was the reason its claim 1-4 were invalidated; that is, a faulty definition resulted in in claims 1-4 being found anticipated. The specification and the prosecution history are intrinsic evidence which is reviewed first when construing a claim term.6 If the intrinsic evidence is inadequate to define a term, then extrinsic evidence in the form of dictionaries, treatises, and expert testimony is utilized to determine substantial evidence, which is relevant factual evidence that would lead a reasonable mind to accept as sufficient to support a legal conclusion.7 If there are “several reasonable but contradictory conclusions,” the Fed Circuit will still find the PTAB’s decision to support one conclusion over another plausible alternative as valid.8

The PTAB determined “package” as meaning “a package including, but not limited to a package produced from Knowles’s two mounting methods.”9 In other words, the PTAB did not restrict the “package” definition to one requiring connection with a mounting mechanism, while Knowles argued that it did. The Fed Circuit panel, consisting of Judges Wallach, Chen, and Newman, with Judge Wallach writing for the majority, found that the PTAB’s definition correct. First, claims 1-4 do not specify the type of connection required to form the MEMS package. Further, the extrinsic evidence demonstrated that “package” could be defined by qualifying language which did not limit the connection to circuit boards by only the two types of mounting that Knowles had argued as part of the definition. And finally, and perhaps most damaging, neither the ‘231 specification nor its claims gave a proper definition for “package” that would inform a POSITA a favored interpretation.10

Knowles made a final argument that Fed Circuit precedent had already defined “package,” which was construed as “a self-contained unit that has two levels of connection, to the device and to a circuit or other system.”11 The majority disregarded this argument, stating that in that case, MEMS Technology, the package did not require a mounting mechanism, and therefore, that definition did not apply to the present case.

As to the inadequate written description to support proposed claims 23-27, because the ‘231 specification only disclosed the genus – solder pads – to connect the package to the circuit board, rather than the species – solder reflow process – which is disclosed in the proposed claims. As such, a POSITA would not be able to determine whether the inventor invented the invention as written in proposed claims 23-27.

Judge Newman’s dissent was vociferous in her insistence that precedence defined “package,” and that that definition should have been applied in this case. Judge Newman had immediate problems with the PTAB not applying a final judicial decision of the same issue of the same claim.

The purpose whereby the PTAB was created as an agency tribunal, in order to provide stable law and economical determination of patent validity, is negated when final adjudication in a court of last resort may be ignored, and the issue litigated afresh in an agency tribunal.12

She reiterated that the Supreme Court held that issue preclusion (i.e., collateral estoppel) would be recognized except when the statute provided otherwise.

A prior judicial decision resolving the same issue is accorded preclusive effect not only in subsequent court proceedings but also before an administrative agency, subject only to the established equitable and due process exceptions to preclusion.13

Further, she noted:

While precedent has previously addressed the effect of a prior district court claim construction on a subsequent USPTO proceeding, never before has a final claim construction by this court been held not to be preclusive (emphasis added).14

Judge Newman emphasized her point that in this case, “package” was already defined in the MEMS Technology case, and therefore, “preclusion should apply.” Judge Newman’s dissent ends with a high-end recitation of the doctrine of collateral estoppel and its importance with AIA proceedings:

The purpose of the America Invents Act is to provide a more efficient and less costly post-grant determination of certain validity issues, compared with the time and cost of court litigation. Such purpose is negated by duplicate USPTO litigation of the same question after prior final judicial decision. Such duplicate proceeding is appropriately governed by the principles of collateral estoppel … . Under the judicially-developed doctrine of collateral estoppel, once a court has decided an issue of fact or law necessary to its judgment, that decision is conclusive in a subsequent suit based on a different cause of action involving a party to the prior litigation.15

This conflict between court decision and agency obligation raises issues of litigation and patent policy, as well as invoking the fundamentals of stare decisis and separation of powers. The adjudication of questions of patent law takes on special significance in light of the purposes of the America Invents Act. The purposes of efficiency, economy, and finality of patent review are lost when judicial determination of the same question of patentability has been completed, including appeal to and decision by the Federal Circuit – yet the decision is ignored and the proceeding repeated by the administrative agency and again appealed to the Federal Circuit; and where, as here, the Federal Circuit reaches a contrary decision.16

To be sure, Judge Newman has deep concerns of the effects of this case on future PTAB decisions, and the Fed Circuit’s passive review of collateral estoppel issues. This author actually agrees with her. Collateral estoppel helps develop stability in the law. In recent years, patent law has gone through numerous changes, especially on patent-eligibility and obviousness. Consistent court rulings is necessary for practitioners to develop the practice by creating stable case law for the practitioner in areas of deep fluctuation, like patent-eligibility and obviousness.

Will this case be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court? We shall see.

Footnotes

-

___F.3d___ (Fed. Cir. 2018), aff’g Cirrus Logic, Inc. v. Knowles Elecs. LLC, 2015-004342, 2015 WL 5272691 (PTAB Sept. 8, 2015) and 2016 WL 1378707 (PTAB Apr. 5, 2016) (rehearing denied). ↩

-

See 35 U.S.C. §112(a). ↩

-

Knowles, supra (slip op. at 3). ↩

-

See MPEP 2111.01: “under a broadest reasonable interpretation, words of the claim must be given their plain meaning, unless such meaning is inconsistent with the specification.” ↩

-

See Microsoft Corp. v. Proxyconn, Inc., 789 F.3d 1292, 1297-98 (Fed. Cir. 2015). ↩

-

Id. at 1297. ↩

-

See In re Jolley, 308 F.3d 1317, 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2002). ↩

-

Knowles, supra (slip op. at 6). ↩

-

See MPEP 2173.05(a): “the meaning of every term used in a claim should be apparent from the prior art or from the specification and drawings at the time the application is filed. Claim language may not be ‘ambiguous, vague, incoherent, opaque, or otherwise unclear in describing and defining the claimed invention.’” ↩

-

Knowles, supra (slip op. at 10); see also MEMS Tech. Berhad v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 447 F.App’x 142, 159 (Fed. Cir. 2011). ↩

-

Knowles, supra (slip op at 2) (Newman, J. dissenting). ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Id. (slip op at 3-4) (Newman, J., dissenting), citing Montana v. United States, 440 U.S. 147, 153 (1979). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 5) (Newman, J., dissenting). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent