On February 14, 2018, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed down Aatrix Software, Inc. v. Green Shades Software, Inc.,[1] which signals a possible sea change in the §101 patent-eligibility analysis and potentially give patent holders some ammunition to fight invalidation of their patents. This opinion also tracks the rather complex federal court procedural rules, but it is these rules which go to the final disposition of the case.

The facts are as follows.

Aatrix Software owns U.S. Patent Nos. 7,171,615 (‘615) and 8,984,393 (‘393) both for “Method and apparatus for creating and filing forms.” Aatrix sued Green Shades for patent infringement in the U.S. District Court, Middle District of Florida.

Claim 1 of ‘615 was deemed representative:

- A data processing system for designing, creating, and importing data into, a viewable form viewable by the user of the data processing system, comprising:

(a) a form file that models the physical representation of an original paper form and establishes the calculations and rule conditions required to fill in the viewable form;

(b) a form file creation program that imports a background image from an original form, allows a user to adjust and test-print the background image and compare the alignment of the original form to the background test-print, and creates the form file;

(c) a data file containing data from a user application for populating the viewable form; and

(d) a form viewer program operating on the form file and the data file, to perform calculations, allow the user of the data processing system to review and change the data, and create viewable forms and reports.[2]

(Emphasis added.)

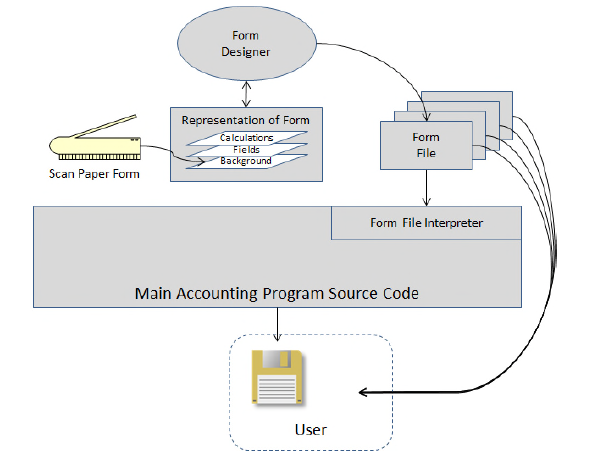

The claimed invention can be depicted as follows:

Source: Second Amended Complaint, Aatrix Software, Inc. v. Green Shades Software, Inc., No. 3:15-cv-00164-HES-MCR, filed April 26, 2016, USDC, MDFL

The district court found claims 1, 2, and 22 of ‘615 and claims 1, 13, and 17 of ‘393 invalid as directed to patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. §101, and dismissed under Rule 12(b)(6), as well as denied Aatrix’s motion to amend the complaint, and include its second amended complaint, so that additional factual allegations could be entered into the case.

As a preliminary matter, the Fed Circuit panel, consisting of Judges Moore, Reyna, and Taranto, noted that “patent eligibility can be determined at the Rule 12(b)(6) stage.”[3] If there are factual allegations which prevent resolution as a matter of law, such as claims construction issues, the court must either accept the non-movant’s constructions[4] or the court itself must resolve the dispute to the full extent to complete a proper §101 analysis.[5] Further, the panel noted that the district should “freely give leave to amend a complaint ‘when justice so requires.’”[6]

The panel found that the district court erred by granting the 12(b)(6) motion without a claims construction on claim 1 of ‘615, and further, erred in denying Aatrix’s motion to amend its complaint.[7] The second amended complaint, which the district court denied its entry, would have alleged facts that would have directly changed the patent-eligibility analysis. The facts in the second complaint include factual disputes over the claim term “data file” and whether it is an “inventive concept.”[8] Further, there were allegations in the second complaint which went to the inventive concepts of the claimed form file technology. In doing so, the district court was erroneous in denying the entry of the second amended complaint, and granting the 12(b)(6) motion.

As to the substantive patent-eligibility issue, 35 U.S.C. §101 requires a the claims of a patent to be directed to a patent-eligible subject matter. [9] In Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l,[10] the U.S. Supreme Court enunciated a two-step test to determine whether a claim was patent-eligible. First, the invention is determined whether it falls into a judicial exception: law of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract idea. [11] Then, if so, the claim must be analyzed to determine whether it contains an “inventive concept” to transform the claim into a patent-eligible invention. “Inventive concept” requires an element or combination that makes the invention significantly more than just the abstract idea.[12] Aatrix’s complaint alleged that it was an “invention [increased] the efficiencies of computer s processing tax forms.” Further, the invention reduces “thrashing,” which is a condition of computers being slowed down as a result of the extra memory required for using the prior art’s tax software program. Aatrix’s invention reduced the thrashing which made the computer process the forms more efficiently.[13] The panel rationalized that because of this allegation, Aatrix’s claims were directed to an improvement in computer technology rather than a mere component of computer-related activities.[14] This suggested “something more” than just a mere judicial exception.

Dealing with the second step of the Alice test, the panel went further into errors made by the district court in not entering Aatrix’s second amended complaint because of factual allegations which would create a factual dispute as to what was conventional or routine in Aatrix’s claimed invention. Further, the panel noted that neither the district court nor Green Shades made any proper basis for rejection of these allegations as a factual matter.

Whether the claim elements or the claimed combination are well-understood, routine, conventional is a question of fact. And in this case, that question cannot be answered adversely to the patentee based on the sources properly considered on a motion to dismiss, such as the complaint, the patent, and materials subject to judicial notice.[15]

Specifically, the panel noted:

Aatrix cites the specification as support for its argument that the claimed data file contains an inventive concept directed to improved importation of data and interoperability with third-party software. It explains that through the data file, “data from the vendor application is seamlessly imported into the program” and the data file imports “only the data for a selected reporting period based on the guidelines programmed into the forms.”[16]

The panel took the district court’s analysis as almost negligent because it failed to support the finding that Aatrix’s “data file” construction was “well-understood and routine” with well-reasoned evidence of any kind. As a result, both the Rule 12(b)(6) dismissal and the dismissal of the motion to amend the complaint were overturned because there were factual allegations made that make patent-eligibility invalidation under §101 inappropriate.

Judge Reyna dissented the use of factual evidence in a §101 analysis. His major concern with making a §101 decision based on factual evidence as:

The risk of this approach is that it opens the door in both steps of the Alice inquiry for the introduction of an inexhaustible array of extrinsic evidence, such as prior art, publications, other patents, and expert opinion.[17]

In essence, he believes that a §101 analysis remains a question of law, and not a question of fact.

Aatrix represents the fourth precedential case just in 2018 issued by the Fed Circuit that has found claims patent-eligible; up through 2017, it has taken nearly four years post-Alice to get almost that many cases. This is also the second precedential decision (after Berkheimer) that finds a factual allegation presented in the case could create a scenario of claims overcoming a §101 eligibility problem. Tactically, this is a procedural shift to limiting §101 judgments early in litigation, like at the summary judgment or 12(b)(6) stage.

The bigger question remains whether the change to a factual question analysis raises the possibility of an imminent en banc decision to solidify the new change in §101 patent-eligibility. With Aatrix adding to Finjan, Core Wireless, and Berkheimer as precedential §101 decisions favorable to the patent holder. With the requirement of a question of fact analysis found in Berkheimer and Aatrix, a core group of judges could be composed of Judges Moore, Taranto, and Stoll, who were in the majority of both of these cases. Add to this group Judges Dyk, Linn, and Hughes who signed on to the Finjan opinion, and possibly Judge O’Malley (majority in Core Wireless), and this could make up the majority opinion, signaling a change in the §101 patent-eligibility analysis by including questions of fact into the equation. This would, in general, help the patent holder in an IPR before the PTAB and give them a relatively good fighting chance at saving their patents from invalidity in the courts. We shall see.

[1] 882 F.3d 1121 (Fed. Cir. 2018), rev’g, vac’g and remanding, Aatrix Software, Inc. v. Green Shades Software, Inc., Case No. 3:15-cv-00164-HES-MCR (M.D. Fla. Feb. 5, 2015).

[2] Id. (slip op. at 3).

[3] Id. (slip op. at 5) (citing Genetic Techs. Ltd. v. Merial LLC, 818 F.3d 1369, 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2016). Rule 12(b) outlines the process for a federal defendant to raises defenses and objections, including filing motions to counter the claims made in the complaint. Rule 12(b)(6) specifically allows a defendant to make a motion alleging “failure of the complaint to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.” See F.R.C.P. Rule 12(b).

[4] See BASCOM Glob. Internet Servs., Inc. v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 827 F.3d 1341, 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Content Extraction & Transmission LLC v. Wells Fargo Bank, Nat’l Ass’n, 776 F.3d 1343, 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

[5] See Genetic Techs, supra at 1373.

[6] See Aatrix, supra (slip op at 7); see also F.R.C.P. 15(a)(2).

[7] Id. (slip op. at 6-7).

[8] Id. (slip op. at 8-9).

[9] See 35 U.S.C. §101 (“Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor . . . . “).

[10] 573 U.S.___, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).

[11] Id. at 2354-55.

[12] Id. at 2355.

[13] See Aatrix, supra (slip op. at 10).

[14] See Visual Memory LLC v. NVIDIA Corp., 867 F.3d 1253, 1258-59 (Fed. Cir. 2017); Amdocs (Israel)Ltd. v. Openet Telecom, Inc., 841 F.3d 1288, 1300-02 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

[15] See Aatrix, supra (slip op. at 11-12).

[16] Id. (slip op. at 13).

[17] Id. (slip op. at 2) (Reyna, J., dissenting).