Fed Circuit Watch: Litigation Misconduct and Inequitable Conduct

By Brent T. Yonehara

On July 27, 2017, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Merus B.V. In Regeneron, the Federal Circuit affirmed a district court’s finding that Regeneron’s patent 8,502,018 was unenforceable due to inequitable conduct.[1] This case brings up the Therasense New Order of Inequitable Conduct in patent cases.

The law of inequitable conduct has slowly begun to take shape seven years after Therasense1 was decided by the Federal Circuit. In Therasense, the Federal Circuit enunciated the elements for determining an inequitable conduct defense. First, there must be materiality. Second, there must be intent to deceive the USPTO. 2

To start with, the duty to disclose and deal in good faith with the USPTO in patent applications extends to the patent applicants, owners, inventors, and patent practitioners of the application.3 All of these individuals must disclose information material to patentability (emphasis added).4 A prima facie case of unpatentability is established when the information demonstrates that a claim is unpatentable under the preponderance of evidence, with each claim term given its broadest reasonable interpretation consistent with the specification.5 Also, information is not considered material if it is cumulative to information already of record.6

Further, these individuals must also have a specific intent to deceive the USPTO by failing to disclose information as to the patentability of the claim in question; this must be proved by a much higher clear and convincing evidence standard.7 While a direct intent is rarely proven, an inferred intent can be made from indirect and circumstantial evidence which must be the “single most reasonable inference able to be drawn from the evidence.”8

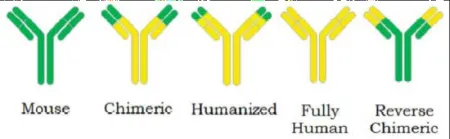

In Regeneron, the patent practitioners failed to disclose four prior art references cited by third parties in related U.S. and foreign prosecutions. The Regeneron practitioners alleged that while the references withheld is not in dispute, the references themselves were merely cumulative of what was already in the file wrapper. The subject matter of the ‘018 patent in question was the mouse-human chimera, or genetically modified mouse, for purposes of developing genetically modified mouse antibodies to be used in humans to combat certain bacteria or viruses. Claim 1 recited:

- A genetically modified mouse, comprising in its germline human unrearranged variable region gene segments inserted at an endogenous mouse immunoglobulin locus.

Regeneron had argued that under the broadest reasonable interpretation, Claim 1 was limited to a reverse chimeric mouse. In other words, Regeneron argued for a much narrower construction. However, Merus argued that constant region of the gene segments in the claimed mouse contained either mouse or human genes, and could be reverse chimeric, humanized, or fully human. Thus, Merus argued a broader construction of Claim 1.

The court found that the transitional phrase “comprising” was an open-ended term, use of the term did not exclude unrecited elements.9 Therefore, the germline was not just limited to mouse and also included human, which further meant the claim language included reverse chimeric, human and fully human genes.10

On the intent requirement, inferred intent to deceive was demonstrated by Regeneron’s in-house patent practitioner’s failure to produce discovery documents relevant to the prosecution of the ‘018 patent. This was deemed the litigation misconduct. Further, Regeneron had an intent to deceive because their in-house counsel failed to submit the four prior art references during the prosecution of the ‘018 patent, as it was in the belief of the in-house counsel that the references were not material to patentability. The Federal Circuit pointed out that “Regeneron’s litigation misconduct [] obfuscated its prosecution misconduct.”11 Thus, the Federal Circuit held the district court did not abuse its discretion by drawing an “adverse inference of specific intent to deceive”12 on the part of Regeneron.

Inequitable conduct is a serious issue in prosecution because, as a defense, and if used successfully, it could not only invalidate one claim of a patent but also the entire patent is found unenforceable, which cannot be cured by a reissue.13 This may be the reason why these cases have convoluted and lengthy histories because these issues could not be resolved back in the PTAB.

Another post-Therasense case, American Calcar v. American Honda Motor Co., 14 also went through the numerous machinations of the federal court system, and also turned out badly for the plaintiff. In that case, a car guidance system patent were at issue. The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s ruling that the patent was invalid under §§102 and 103, and unenforceable due to inequitable conduct due to inventor’s failure to submit prior art.

As for the intent requirement, the court determined that the Calcar inventor knew that his photos of the Honda Acura car were material to patentability, and therefore, withheld them from the Examiner. In doing so, the Calcar inventor had the specific intent to deceive the USPTO because there was an inference the inventor had undisclosed information about the Honda Acura car system (i.e., the prior art), he knew it was material, and, further, he deliberately withheld it from disclosure as required under 1.56.

These line of cases show that the there are ramifications post-prosecution, and that intent to deceive is not just limited to strictly those required under their 1.56 duty (i.e., the litigation counsel further downstream). Further, as shown with Regeneron, intent to deceive can go back upstream to the original patent prosecutor when the litigation counsel way down the river engages in litigation misconduct (i.e., it could lead to disciplinary action before the OED). Based just on this most recent case, the case law is beginning to show a trend of broad interpretation of intent to deceive and materiality required to show inequitable conduct. As such, this case should be of deep concern for all patent practitioners.

Footnotes

-

Therasense, Inc. v. Becton Dickinson & Co., summ. j. granted, 560 F. Supp. 2d 835, 854, aff’d, 565 F. Supp. 2d 1088, 1127 (N.D. Cal. 2008), aff’d, 593 F.3d 1289, 1311 (Fed. Cir. 2010), reh’g granted, vacated & remanded, 649 F.3d 1276 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (en banc), aff’d upon remand, 864 F. Supp. 2d 856, 858 (N.D. Cal. 2012), aff’d on other grounds, 745 F.3d 513 (Fed. Cir. 2014). ↩

-

Id., 649 F.3d at 1290-91. ↩

-

See 37 C.F.R. §1.56(c); MPEP 2001.01. ↩

-

See 37 C.F.R. §1.56(b); MPEP 2001.05. ↩

-

See MPEP 2001.05. ↩

-

See 37 C.F.R. §1.56(b). ↩

-

See Therasense, supra, 649 F.3d at 1287, 1290. ↩

-

Id. (citing Star Scient. Inc. v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., 537 F.3d 1357, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2008). See also Regeneron, supra (slip op. at 40) (Newman, J., dissenting) (noting that inferred intent must still be proven, and “absence of trial findings cannot be substituted by inference.”). ↩

-

See MPEP 2111.03 (“[t]he transitional term ‘comprising,’ … is inclusive or open-ended and does not exclude additional, unrecited elements or method steps.”) ↩

-

See Regeneron, supra (slip op. at 5-6, 13-14). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 37). ↩

-

Id. (slip op. at 38). ↩

-

See MPEP 2016 (“once a court concludes that inequitable conduct occurred, all the claims … are unenforceable.”); MPEP 2012 (“both 35 USC 251 and 37 CFR 1.175 … require that the error must have arisen ‘without any deceptive intention.’”). ↩

-

Am. Calcar, Inc. v. Am. Honda Motor Co., Inc., Case No. 06-cv-02433, 2008 WL 8990987 (S.D.Cal. Nov. 3, 2008), vacated and remanded in part, 651 F.3d 1318 (Fed. Cir. 2011), aff’d upon remand, Case No. 06-cv-0233, 2012 WL 1328640 (S.D.Cal. Apr. 17, 2012), aff’d, 768 F.3d 1185 (Fed. Cir 2014). ↩

Brent T. Yonehara

Founder & Patent Attorney

Founder Brent Yonehara brings over 20 years of strategic intellectual property experience to every client engagement. His distinguished career spans AmLaw 100 firms, specialized boutique I.P. practices, cutting-edge technology companies, and leading research universities.

More About Brent